Archive Page 24

October 10th, 2015 by dave dorsey

In the New York Times book review this Sunday, Jonathan Franzen used a term familiar to me only from Martin Heidegger’s writings on technology. As result I got curious to know how Thomas Sheehan’s recent book about the German thinker has been received. I didn’t come across any reviews with a Google search, but I did find a paper he’d written last year, “What, After All, Was Heidegger About?”, which serves almost as an overview of the new book, which I haven’t finished. The paper is far easier to understand than the book simply because it’s less laden with un-transliterated Greek words (there are still plenty) and the footnotes are easy to delete and ignore if you copy and paste the content into Word. How’s that for a workaround to avoid distractions? (My apologies to Sheehan’s assiduous attributions demonstrating the depth of his comprehensive scholarship on the German philosopher.)

I’ve read the paper a couple times and may post a reaction to it. I’m no authority on philosophy, but I still read it as part of an effort to cobble together, slowly and haltingly, a view of what painting has the potential to do, when it is at its best. Heidegger’s thinking represents a personal cornerstone in this effort, based on what little he wrote about visual art–though Sheehan’s essay doesn’t address the philosopher’s views in a way that helps me much with that right now. Still, it’s lucid and brief and apparently controversial among some core Heideggerians. But this is what I gather second-hand, because I don’t “follow” philosophy. I’m a layman dogged by philosophic questions, and I have only few un-entitled opinions to air about it.

Which brings me to the good news. Entitled Opinions, where I discovered Sheehan, is back! I’m only two podcasts behind in the new season. The Stanford University radio program had been gone for more than a year. I can’t wait to hear Robert Harrison’s new discussions as they become available. I can hear echoes, in the paper, of things said in conversation with Harrison, about how Heidegger did little to address the subject of ethics as a philosopher (and made some questionable ethical/political choices as an individual). But mostly the content of the paper is distinct from much of what Sheehan has said about Heidegger on this podcast. I hope he’s on deck, or at least somewhere in the season’s line-up, to talk at length about his new paradigm for understanding the philosopher.

October 8th, 2015 by dave dorsey

This made me laugh, as was intended, maybe because Renoir is my least-favorite Impressionist. BBC coverage of an anti-Renoir demonstration:

The Boston Globe reported that they chanted: “Put some fingers on those hands! Give us work by Paul Gauguin!” and “Other art is worth your while! Renoir paints a steaming pile!”

October 1st, 2015 by dave dorsey

Gifts, oil on linen, 53 x 53

1

Starting this spring, and all through the summer, I’ve worked on only one painting. I’ve never invested this many calories into a single painting, this much obedience to the act of looking at a particular set of objects. I suppose this can’t be an entirely good thing for a person, but I’m pleased with the results. For me, painting is rhythmic, like factory work—you do a certain amount each day, on a regular basis, and at the end of X number of days you have a painting. This one has been different. Most days, since early May, I’ve put in several hours of writing every morning, first thing, usually from 6 a.m. to 9 a.m., which enables me to pay the bills, then another four to six hours of painting, seven days per week. I took much of July off, in the middle of all this, when I went sort of rogue, insofar as that’s possible at my age, and I rode 1,700 miles around New England and into Canada on my eleven-year-old BMW R11050R motorcycle, mostly staying with friends. Then I came home and got back to painting, wielding my brush with the wrist I’d made sore during a couple weeks of using it to twist a throttle. Around four each day I would settle into a chair for a while or go for a run. Writing this blog took a backseat, as did most other things. My absorption with this painting drew me away from a number of other activities, and last week I more or less finished it. I say that provisionally, since no painting is ever finished until you store it somewhere you won’t see it again, preferably in the home of a new owner–or send it off for exhibition. I’ve already entered in in a show at Manifest, so that means it’s done.

This newest painting is an overhead views of a tabletop’s corner, with wedges of Persian carpet beneath, and various household objects strewn at random over the white tablecloth, some like tropical birds perched on snow. I’ve been doing these tabletops for twenty years, probably finishing a dozen of them in all, and I think I secretly hope this one will be the last. I undertook it partly as an effort to complete a definitive version of this personal genre.

I started doing these tables in the 80s after a long obsession with Braque. MORE

September 30th, 2015 by dave dorsey

I’m emerging from a tunnel of work on a single painting I began in May and finished last week, so I’m only now catching up with what friends have been up to over the summer. Rick Harrington moved back to the Northwest, where he grew up, and is now living and working in Portland. I was sorry to hear he was going to be on the other side of the country, probably from now on, but I hope to keep in touch, and I also hope he keeps exhibiting at Oxford here.

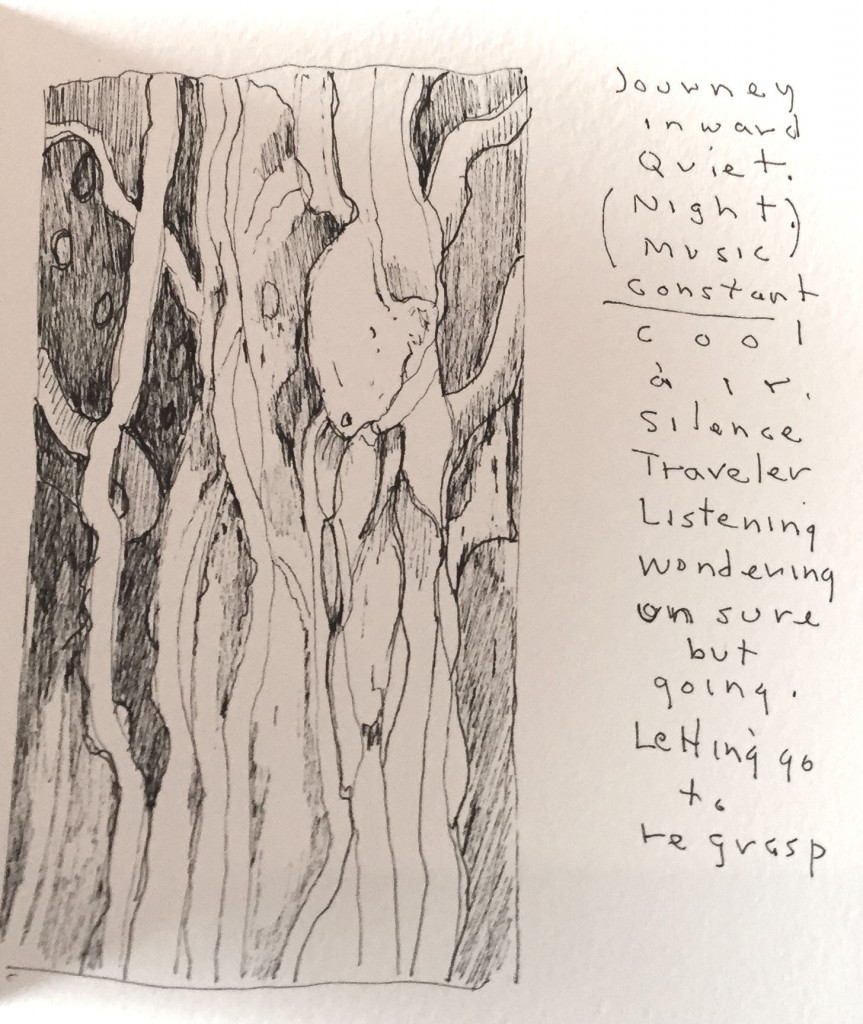

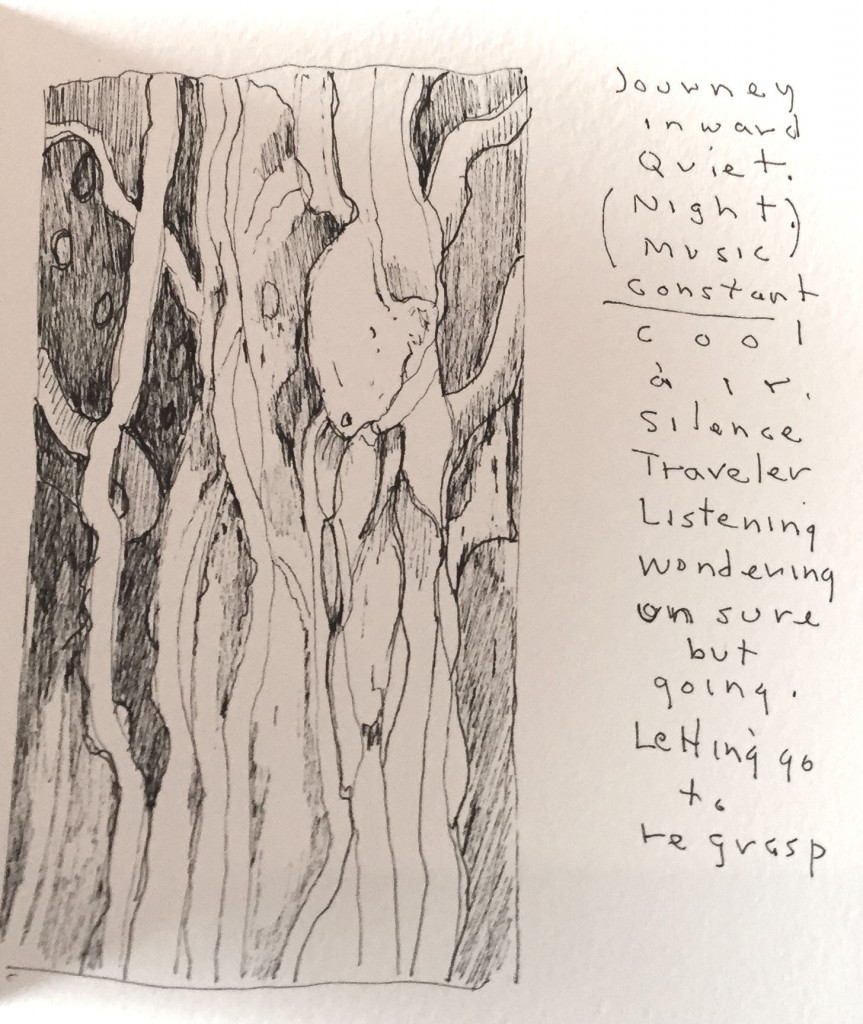

Bill Stephens has been on the road this summer, heading east to a retreat and then west to travel around the mountains and do sketches of what he was seeing. He’s creating notebooks that are a nice combination of text and image that he ought to try selling, a little touch of Basho on his journey. The line drawings in ink are assured and fresh and calming. With an economical use of line he puts me wherever he was from one day to the next. I’ve posted one of them above.

Bill Santelli is very busy, showing his work both here in the next Oxford Gallery show and right now at ArtPrize in Grand Rapids, Michigan. ArtPrize is an open international art competition decided by public vote and expert jury. It awards grants to 25 recipients, and has as well as offering a Fellowship for Emerging Curators program. The $500,000 competition runs from September 23–October 11.

My friend Rush Whitacre is teaching now at Washington State Community College, and he’s recruiting people for a fantastic tour of Italy next March: 10 days and six cities, Rome, Florence, Venice, Assissi, Sorento and Pompeii. You can learn more and sign up here. If I had the money to spare, I’d already be signed up.

Jim Mott is still on the road, as far as I can tell. He’s usually off the grid as he makes his way across the country and stays with his hosts on one of his itinerant painting trips. He ought to be somewhere in California by now. Send some images of what you’re doing, Jim, if you see this.

September 28th, 2015 by dave dorsey

High Falls, Bryce Ely, oil on board

There’s a great show in its final days at Oxford Gallery, abstractions from two artists whose work took me by surprise. The invitation card didn’t convey how effective their best paintings are, and, as usual, the work was powerful insofar as I was mystified by what exactly enabled their imagery to succeed. I’d seen Phyllis Bryce Ely’s work before, when it won an award in the Memorial Art Gallery’s biennial Finger Lakes Exhibition in 2013. I admired her style without finding myself arrested by it as I walked around the exhibit back then. This time, I found myself coming back many times to particular paintings, seeing more as I stayed with it. Her work hovers right on the cusp between representation and abstraction. It’s always a distillation of a landscape, often involving swirling or falling water. This time, moving from one painting to another, I was reminded of both Charles Burchfield and Arthur Dove, yet her work departs from both influences. Where these two earlier artists were more concerned with careful depiction of a heightened vision of nature, Ely wants to create and convey a quiet energy by giving priority to the paint itself, making visible the way it flows from her brush, creating line and form with the edges of her strokes and slightly unpredictable modulations of tone that flow from the brush as it moves. (Many artists try to paint this loosely; it takes a gift to make it work as consistently as Ely does.) It gives her a special affinity with the subject of moving water–her paint seems a slow, loping doppleganger of the rushing flow it enables you to see. She’s very much in your face about how she pushes paint around. It’s the first thing that meets the eye, before your eye resolves the paint into a scene. Her most effective work looks as if, with Welliver, there’s not much “going back over” for her. So she’s also in a zone between what’s spontaneous and what’s calculated, and yet despite this irrevocable quality in how she applies the paint, the effects are often amazingly evocative–she’s still rendering a scene, with subtle effects of depth and distance, inspiring you to feel there’s more detail in the image than is actually there. With so much emphasis on the surface, and the quality of the paint, you still have a distinct and subtle assurance of a hazy, glowing light source. Or to put it in layman’s terms: you clearly see the, uh, sunlight. It’s remarkable. She makes you imagine more than she requires herself to show, which is the magic of painting at its best. Her technical mastery, from one painting to another, conveys a vision of nature in turbulent motion, but going nowhere in particular, an illuminated world giving a cold shoulder to the eye that eagerly takes it in.

Todd Chalk, of Buffalo, has included some of her latest work–I counted three different personal modes. Some are more conventional abstracts. One especially powerful and effective small painting represents a glance upward through bare branches into an illuminated sky–it’s one of the best pieces in the whole show–and, finally, a series of square watercolors on yupo paper. I confess I’d never heard of that paper before, but it sounds like the perfect support for the green-minded crowd: synthetic, yet recyclable and “100% tree-free” as a promotional website puts it. I love it when artists explore unusual materials, and in this case, the qualities of what seems to be primarily an industrial paper made her intricate, small abstracts fresh, crisp and vibrantly colored. Watercolor on waterproof paper suggests an unconsummated tension as paint and paper fail to merge. She puts that romantic suspense to use: by keeping all the pigment right on the white surface it adds a special intensity to her beautiful explorations of color. Chalk has created a suite of improvisations with color and form, composing intricate Klee-like inner worlds as layered with overlapping tones as a looping song. For an artist thriving and innovating into her eighth decade–if her listed birthdate is true–these paintings offer hope for all of us embarking into the final third of our lives.

Todd Chalk, of Buffalo, has included some of her latest work–I counted three different personal modes. Some are more conventional abstracts. One especially powerful and effective small painting represents a glance upward through bare branches into an illuminated sky–it’s one of the best pieces in the whole show–and, finally, a series of square watercolors on yupo paper. I confess I’d never heard of that paper before, but it sounds like the perfect support for the green-minded crowd: synthetic, yet recyclable and “100% tree-free” as a promotional website puts it. I love it when artists explore unusual materials, and in this case, the qualities of what seems to be primarily an industrial paper made her intricate, small abstracts fresh, crisp and vibrantly colored. Watercolor on waterproof paper suggests an unconsummated tension as paint and paper fail to merge. She puts that romantic suspense to use: by keeping all the pigment right on the white surface it adds a special intensity to her beautiful explorations of color. Chalk has created a suite of improvisations with color and form, composing intricate Klee-like inner worlds as layered with overlapping tones as a looping song. For an artist thriving and innovating into her eighth decade–if her listed birthdate is true–these paintings offer hope for all of us embarking into the final third of our lives.

September 27th, 2015 by dave dorsey

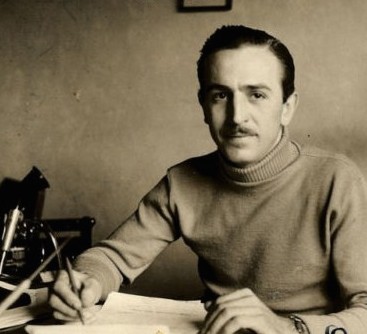

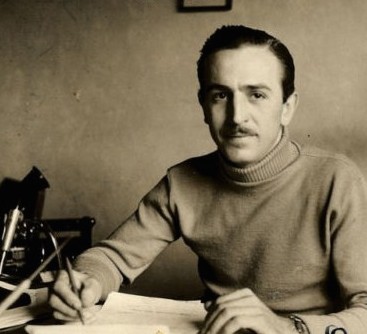

There was a fantastic two-part bio of Walt Disney on PBS recently. It’s worth the time if you have a chance to see it. Here is a near-quote from the broadcast about a time in his life I considered one of the most interesting moments in the story:

Underway was Cinderella. . . he seemed wary of fully investing himself in his film. Yet he left most of the hard work to his staff. Disney was . . . beginning to wear down and he kept a trained nurse in the studi0. Hazel George showed up every day to massage his back and his hips . . . she becomes one of those very few figures in his life . . . with whom he could talk. It wasn’t a sexual relationship but she was one of those figures with whom he could say anything and everything. It was difficult to say he had any close friends with whom he could share . . . he thought I’m never going to make anything as good as Snow White.

She suggested he attend a model train convention in his home state of Illinois . . . so he goes. The ride transforms him. When he arrives back home, Walt Disney was building these trains with his own hands. All in the zest for invention, for creating fantasies . . . Walt was happy to have the good reviews of Cinderella, but it was no Snow White as far as he was concerned. He builds a scale model of the old Marceline (his impoverished childhood home) barn for hours designing a (railroad) track and the engine. It was the toy he never had as a little kid, something that was pure fun and a pleasure to do. There was more in that train than just fun for Walt. When Salvadore Dali visited . . . Dali was taken aback. Such perfection did not belong to models. “It was comfort and salvation. I can’t control my workers. I can’t control the larger stage, I can’t control my company. . . but this is a world I can create down to the smallest details, down to the tunnels under my wife’s flower bed, that is mine and safe. I want you to work on Disneyland he told one slightly confused artist, and you are going to like it.”

September 25th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Two days ago, I hitched a ride south to Bristol to help my friend, Ed, buy some lumber for a pencil post bed he’s making. He bought more than $500 worth of wood simply to finish the frame for the bed—he’s already made the faceted posts. While he was selecting his long boards, I picked up about $25 worth of scraps, little flat blocks of ash and oak left over from the longer planks someone else had bought. (I’ll use them in small informal still lifes, with a couple objects resting on them, because I want to see what I can make of the raw wood’s texture and grain.) Ed needed a hand because he has a ruptured disk. Surgeons will fuse two of his vertebrae in October and, until then, he has to watch how much he lifts. We talked most of the way down to the little lumber place—it’s a specialty shop located in the Finger Lakes near the Bristol Mountain ski resort. I brought him up to date on the book I’m helping Peter Georgescu put together on income inequality and the need for the private sector to stimulate the economy by raising wages. Peter is a former CEO himself, not an academic. So far, it seems publishers feel more secure if an academic is solving economic issues, rather than someone who actually knew how to make a payroll once upon a time. So we’re involved in—how shall I put it—a gradual process of finding a home for his book.

“That’s what’s wrong with academics,” Ed said, though I hadn’t really offered any criticism of them, per se. I was intrigued by this logical leap, though. He brought it into focus as he talked: when it comes to actual market dynamics, how things get made and bought and sold, in his last job before retirement Ed watched an academic come in and mess with his company, a distributor of electronic components. “Before I retired, a guy took over the company who had never run anything, but he’d been a professor. I had a fantastic group of sales people. They started without much experience but were super smart and full of energy and ideas. This new guy decided that we should get rid of any client who was doing less than a certain level of sales with us. We had hundreds of clients. According to this new rule, we were to say goodbye to all of them but seven. I ended up having more sales people than we had customers. I had to let go of everybody. They were exceptional people. It was unbelievable. I became the only guy on the team because they didn’t need anyone else to handle the customers we had left. You couldn’t tell this CEO anything. He’d made the decision, and that was that. We lost hundreds of customers.”

“Organizational life is always a mess, but that sounds like a sure way to ruin a company,” I said, and then, MORE

September 18th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Paintiing Cart, detail, Brett Eberhardt, oil on panel, 69.5 x 41

September 14th, 2015 by dave dorsey

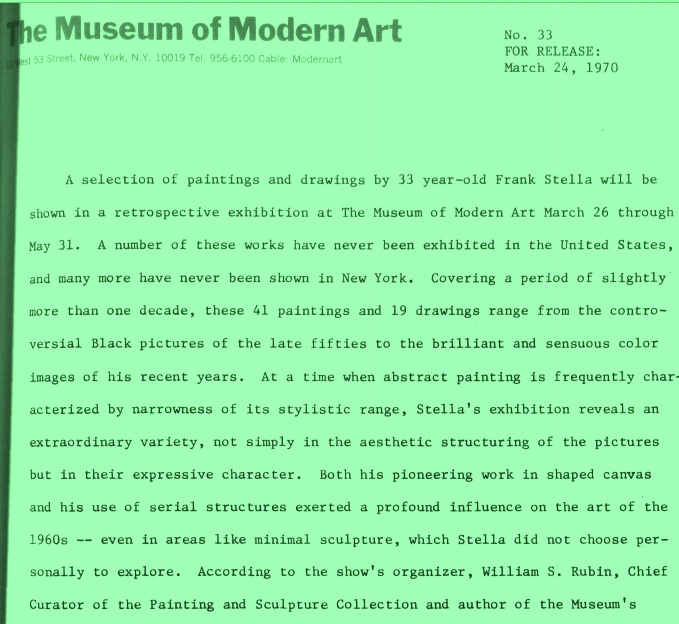

A week ago, as I was looking for a photograph of the Stella catalog I mentioned in the previous post, I came across this pdf of a typed press release from MoMA about a Stella retrospective in 1970. Everything about this bit of public relations made me intensely nostalgic for that period in American art and happy to have stumbled onto something so congenial to my sense of what a painter ought to be. The quotes from Stella at the end are what really made me smile, since there’s such humility and honesty in his words. I especially loved reading the phrase, “the Benjamin Moore” series, named after a brand of house paint. You won’t find a trace of the BS that infects so much talk about visual art in anything Stella says, plus he shares my admiration for Matisse, which makes me love Stella’s work even more:

In the past year, the interlaced, fan and rainbow patterned Protractor series have partly given way to paintings in which the protractor is used to create lyrical, almost floral patterns close in value and tender in their color — the most decorative stage of Stella’s painting. He sums up this recent development: “My main interest [in these pictures] has been to make what is popularly called decorative painting truly viable in unequivocal abstract terms. Decorative, that is, in a good sense, in the sense that it is applied to Matisse….Maybe this is beyond abstract painting. I don’t know, but that’s where I’d like my painting to go.”

September 13th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Frank Stella

There’s a great, lucid profile of the great Frank Stella in this morning’s New York Times: the photograph of him standing with his work in the background says it all. I’ve been working since May on a large still life, another in the series of tabletops, and it depicts, as an earlier one did, a Frank Stella catalog from MoMA, published for a retrospective many years ago. The cover of the book has been difficult to paint, especially the sans serif typeface of Stella’s name, which I’ve done over three times in an attempt to get it right. I may have to settle for “right enough”. We had a few friends here for dinner last night, from our previous neighborhood, and one of them was looking at the nearly-done painting and asked, “Who’s Frank Stella?” I sent him this profile from today’s Arts & Leisure section, about the upcoming Stella show at the Whitney. Without ever saying it in so many words, it conveys, at least for me, that most of Stella’s work has been, if not actually a visualization of joy, at least a reliable source of it. Some of my favorite passages from the piece:

Mr. Stella has done more than any other living artist to carry abstract art, the house style of modernism, into the postmodern era. Yet his passion for form, for contemplating weight and balance, has made him an outlier in an age of nutty auction prices and art that adopts the global economy as its very subject. By his own admission, Mr. Stella does not keep up with the current scene. “In all honesty,” he said, “I never got beyond Julian Schnabel and that generation. He was the ’80s, right?”

What does he think of Jeff Koons, whose shiny balloon dogs and other pop trophies made up the most recent retrospective at the Whitney? “You know what I always thought he was like? The Franklin Mint. He’s from Pennsylvania, and he outdid them. He outshone them! It’s for very wealthy people with no taste.”

Mr. Stella does confess to admiring at least one mid-career artist, Kara Walker, whose monumental sculpture of a sphinx-like deity was displayed to great acclaim in a former sugar factory in Brooklyn last year. “I saw it on YouTube,” he said. “I thought it was interesting.”

And, at the end:

Mr. Stella could have been talking about himself when he told me, “De Kooning was once asked how he felt about celestial space” — the heavens, the stars, and all that. “He said he was only interested in the space he could reach with his hands.”

September 6th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Joy Williams, right, with Bud Schulberg to her left, and Richard Wilbur, far left

Gratitude is the only mood for a painter who realizes the most significant word in this sentence, from an unpublished essay by Joy Williams is “undeserved”: Behold the mystery, the mysterious, undeserved beauty of the world. The second most important word is the one she underlined, of course: behold. Excellent profile of her in today’s New York Times Magazine. The other woman in the shot is Lynn Kaufelt, the author of an obscure book I actually bought long ago on one of our annual visits to Florida: Key West Writers and Their Houses.

September 3rd, 2015 by dave dorsey

Jim’s boots

From Jim Mott:

There is gift-exchange in my life, to be sure, but even I have never had the nerve to try an experiment as full as the one you undertook. Bravo! – Lewis Hyde, author of The Gift, praising Jim Mott’s itinerant art project

Traveling Artist Seeking Hosts for Cross-Country Painting Project: Fall 2015 [2015 tour webpage]

Nationally-recognized landscape painter Jim Mott is celebrating the 15th year of his Itinerant Artist Project (IAP) with a coast-to-coast painting tour this fall, September -December 2015. Traveling New York to California, his route will be determined largely by where he finds volunteer hosts.

Each stop along the way is typically 2-4 days, during which Mott paints a set of small oil paintings in response to the surroundings. One of these paintings is given to the host.

The Itinerant Artist Project – “art for hospitality across America” – is about sharing non-virtual connections, a sense of place, and a sense of life’s journey through art.

You can share the adventure by being a host. Or by forwarding this message to friends and colleagues anywhere who might be interested in the project. This IAP announcement is not just about finding hosts but also about sharing the ideas behind the project. Spreading the word freely, without any need to feel responsible for specific outcomes, is best.

Links:

Email:

August 27th, 2015 by dave dorsey

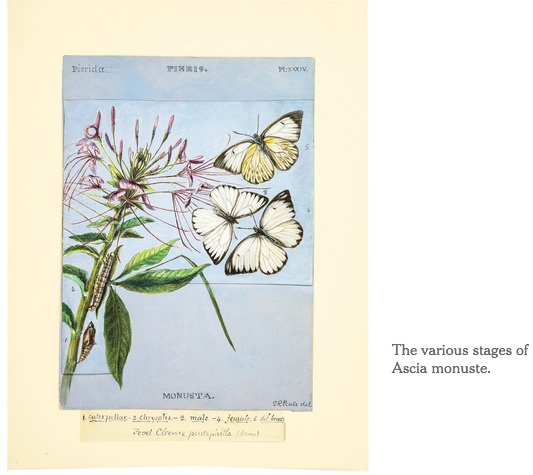

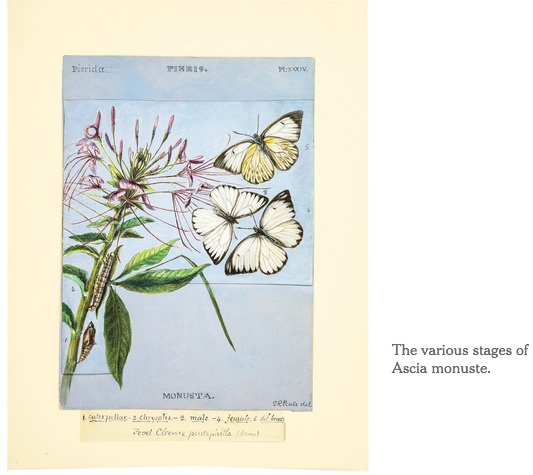

A New York Times review of a book about butterflies and moths, unfinished and never published in its author’s life, sounds as if it’s worth a look. I see there will be illustrations of leaves in it. I’ve been laboring with the job of rendering peony leaves in oil paint over the past couple weeks–it might do my morale good to see how someone else succeeded or fell short in the effort. But I’m interested in this fellow’s project on its own merits. A few days after my wife and I moved into our little A-frame-like gingerbread house in Utica, New York, back in the 80s, we found a cecropia moth slowly fanning its wings on a rock in the little overgrown garden left behind by the previous owners. It seemed more animal than insect. With wings spread, it was as large as my hand. The symmetrical patterns in those scaled appendages, intricate and abstract, looked like eyes or planets. And this, in turn, reminds me that I have yet to write a full response to the fantastic retrospective of Emmet Gowin’s photographs at the Morgan–this book of lepidoptera coincidentally echoes Gowin’s humble, obsessive two-decade photographic pursuit of butterflies and moths in South America.

The book described below, The Butterflies of North America, includes the drawings by a fellow artist/observer, Titian Peale (who seemed to be named after two earlier artists.) Anyone who undertakes any artistic project that stretches over decades is automatically interesting, yet the names of his winged insects alone are a treat:

. . . you’ll discover the Mexican dartwhite and the Pacific orangetip, the yucca and the duskywing skipper, the coontie hairstreak and the sunset daggerwing, the stinky leafwing and the patch checkerspot — not to mention the Eastern comma and the mourning cloak. There are moths here, too: the yellow-necked prominent, the white-marked tussock, the satellite Sphinx and the snout.

The book, unfinished and unpublished when Peale died in 1885, represents more than 50 years of work. The manuscript ended up in the rare book collection of the American Museum of Natural History, where it somehow languished after it was donated by a family member in 1916. All of Peale’s artwork and some of his field notes from the manuscript are being published next week as “The Butterflies of North America: Titian Peale’s Lost Manuscript.”

Peale, who spent much of his life as an assistant examiner with the United States Patent Office, could never have lived up to the original title; there are, after all, several thousand species of Lepidoptera in North America. But what he did leave us is revelation enough.

“Butterflies” features more than 200 works of art — in gouache, watercolor, ink and pencil — that through Peale’s sharp but sensuous eye show the life cycle of moths and butterflies, from egg to caterpillar to pupa to winged adult. These striking illustrations are complemented by notes, studies and sketches in Peale’s hand from his field books.

Peale “considered scientific description and graphic representation entirely commensurate and complementary modes of attention to the natural world,” the art historian Kenneth Haltman writes in the book’s biographical essay.

Each caterpillar, often paired with its preferred food, is precisely drafted. Peale takes clear pleasure in depicting each foot, bristle and segment in tiny strokes. “Walking, bending, and inching up branches, Peale’s caterpillars are a tour de force of observational art,” Tom Baione, director of the museum’s research library, writes in the introduction to the section.

We may marvel at the sheer biological persistence of the 17-year locust, but consider: Titian Peale’s lost illustrations are finally seeing the light of day after a metamorphosis lasting nearly 200 years.

August 18th, 2015 by dave dorsey

New brushes from Dick Blick

Hope and confidence both. Can’t buy me love. Can’t buy me faith. But I can buy a little accessory to hope. Is there anything more like a fresh start than a set of new brushes? For a painting I started in May, granted, but I’m getting that campfire in the gut while working on it.

August 16th, 2015 by dave dorsey

I think I might become absorbed with my tomatoes in tough times as well. The divide between the work and the life is something a lot of critics can’t get past. The personal life is inconsequential compared to the achievement. From The Paris Review:

INTERVIEWER

What happened to your biography of Picasso?

McCULLOUGH

I quit. I didn’t like him. I thought I would do him as an event, the Krakatoa of art. He changed the way we see; he changed the imagery of our time. But then I realized that strictly in terms of what would work for me, his wasn’t an interesting life.

There’s an old writer’s adage: keep your hero in trouble. With Truman, for instance, that’s never a problem, because he’s always in trouble. Picasso, on the other hand, was immediately successful.

Except for his painting and his love affairs, he lived a prosaic life. He was a communist, which presumably would be somewhat interesting, but during the Nazi occupation of Paris he seems to have been mainly concerned with his tomato plants.

And then his son chains himself to the gate outside trying to get his father’s attention; Picasso calls the police to have him taken away. He was an awful man.

I don’t think you have to love your subject—initially you shouldn’t—but it’s like picking a roommate. After all you’re going to be with that person every day, maybe for years, and why subject yourself to someone you have no respect for or outright don’t like?

August 14th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Dan Witz, Agnostic Front Circle Pit, 48″ x 82″, detail, oil/digital media, Jonathan Levine

Pieter Bruegel, Peasant Dance, detail

August 12th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Piet Mondrian, Red Dahlia, 1907, (detail), Opaque and transparent watercolor over graphite on paper. 12 7/16 x 9 7/8 inches Morgan Library

I discovered this watercolor of a dahlia by Piet Mondrian in the Morgan Library’s current retrospective of Emmet Gowin’s photography, a small show that was both astonishing and humbling when I ducked in to see it on my way to JFK on Friday. It’s so great I almost didn’t want to sully it with words, though I’m sure I will soon. Instead, I wanted to stay and study it for a few days, make myself at home, but I had that late flight back to Rochester at Terminal 5. The catalog lists everything on exhibit, but doesn’t offer images of more than a fourth or a third of it, and I was disappointed not to be able to revisit, in the catalog, many of the startling and powerful pieces, reaching back centuries, from the Morgan’s vault that Gowin chose to include in the exhibit. Since I’ve been growing dahlias for nearly a decade and painted many of them, this little revelation surprised and pleased me, especially since it’s so well done, but also because it demonstrated how artists can’t really stick to one thing for long, and how polarities can energize their work.

I had no idea that, while he was realizing his identity in his famous primary-colored grids, Mondrian continued to draw flowers, work that represented the exact opposite of his oils, in formal terms. Nothing could be further from Mondrian’s career-making grids than this dahlia, yet maybe these flowers are precisely what sustained his investigation of the spare music he found in rectangles and squares. (Frederick Hammersley’s dialectic of working in both geometric and organic shapes comes to mind.) Gowin shifted gears a number of times himself and was intensely absorbed by opposing, contrary states: light and dark, harrowing desolation and domestic rapture, butterflies from the rain forest and craters from the wastelands of nuclear testing. I will save for a future post what he communicated to me with these images toggling between garden and gehenna (to adopt the Biblical mythology Gowin absorbed young and then deployed as a foundation for his mature artistic vision and for this show.) His deep immersion in William Blake’s writing and visual art is what drew me to the show, and he’s a worthy heir to Blake in his own photography, an earlier genius who drew from Gnosticism as the foundation for a deeply original vision. Two of Blake’s best, from his illustrations for the Book of Job–both of which I saw previously, in an earlier show at the Morgan–are included alongside Gowin’s photographs.

Gowin is a great soul, and this exhibit is a profound experience, a major discovery of the breadth and depth of his sensibility, and it’s impossible to do justice to it in a blog post. But maybe, if I can respond to this show the way I’d like in a little while, I can encourage a few to see what he’s done, because of the quality of work Gowin produced himself, but also because everything in the show appears fresh and new in the context of this photographer’s long and slow curatorial excavation of art from the Morgan’s permanent collection to pair with his own photography. As the curator of this show, Gowin has put together a visionary work of art itself–everything you see feels as if you’re glimpsing something for the first time. More often than not, it was literally my first look at the work. I felt regret simply pulling myself away from one image hanging on the wall in order to see what was mounted next to it. With the time available to me after a day’s working visit to the city, I picked the one exhibit that could not have been equaled (in the artist’s reverence, awe, decency and quiet authority) by anything else on view in New York City right now. Apparently, my luck continues to hold. And so does my mournful hope that quiet, deeply humble art, grounded in genuine wisdom and an affirmation of all human experience, can prevail. Gowin is a sage. Joseph Campbell would have loved this show.

August 10th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Hsin Wang, No. 24, pigment injet print. From I Love You Bedford, 294 Bedford Ave., Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Aug. 6-24. From the artist’s diary:

” eventually

everyone will

leave me.

I will leave

everyone.

everyone will

leave

everyone. “

August 8th, 2015 by dave dorsey

I like to watch. It’s one of the few things I have in common with Chauncey Gardner. (I’ll let you know if I ever walk on water. Still failing at this point.) A new service will allow me and others to eavesdrop on other artists as they work, and communicate with them as they do their work, though it’s hard to imagine why anyone would want to watch me in the studio. Maybe as a coffee break from the more emotionally taxing act of watching grass grow. It’s called Sywork, (Show Your Work), and it’s in beta at the moment and is mostly a medium for illustrators to get together and learn from one another. It’s an interesting idea though it sounds as if it consumes what I never have enough of–time. From an interview with the founder:

Today, a company called Sywork (shorthand for “Show Your Work”) launched its new live-streaming service for artists and illustrators. Ever wonder what the process is behind beautiful oil paintings? Comic books? Well now you can find out . . .

Each artist has their own channel, which you can subscribe to of course, and you’re notified when they’re live. A few of the illustrators I’ve watched have been heads down making things, with music bumping in the background. Much like Twitch, there’s a chatroom to the right, where people who are watching talk about what they’re seeing.

I spoke to one of Sywork’s founders, Marcelo Echeverria, about the site:

TC: How did you come up with the idea for Sywork?

ME: We are creators ourselves. We’re also big fans of games, movies and comics, and wanted to see our favorite creators livestreaming as they worked.

We were looking for a place where illustrators could show their process and realized that a lot of artists have the same problem. Artists we talked to were trying to find a place to live stream. They were using google hangouts, paid live streaming platforms or even gaming platforms like Twitch. But there wasn’t a place created specially for them.

We want Sywork to be a place where creators can engage with each other and fans, build their audience and make extra money doing it. There are thousands of people who want to watch artists work live. We went to Comic Con this year and saw how passionate people are about their favorite artists.

August 5th, 2015 by dave dorsey

I’m back from my wandering in New England and Canada, 1606 miles on two wheels with a duffel bag, back to the easel and the laptop, and I’m catching up on some DVR content after two weeks almost entirely devoid of TV viewing. I watched Kacey Musgraves open for Dale Watson, the “Antichrist of Country,” on Austin City Limits and in the quick interview following his performance he quoted John Lennon: “One’s originality comes from the inability to emulate your influences.” I loved that quote. It reminded me of how Van Gogh’s failure to be an Impressionist led him to become himself as a painter, as did Braque’s unfulfilled desire to be Cezanne. What seems like a limitation in technique or style can be exactly what lays the ground for authentic work, if you embrace it.