Archive Page 48

July 9th, 2012 by dave dorsey

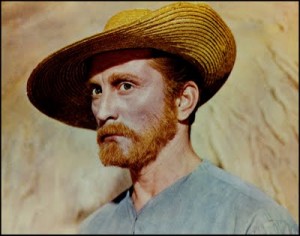

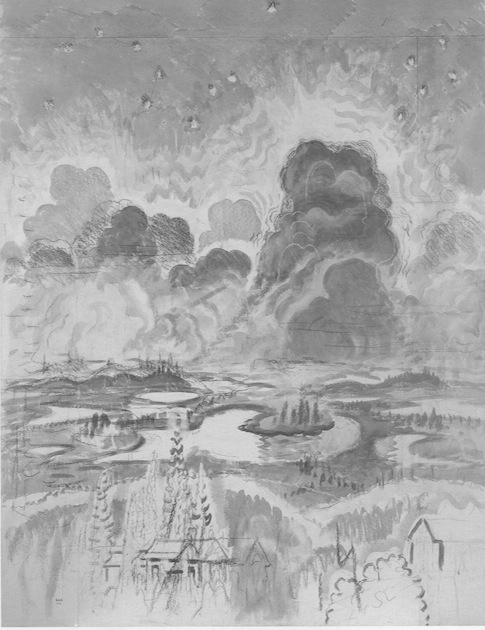

Fait II, Claudia Fainguersch

I spent most of Sunday helping to hang the new group show at Viridian Artists, on W. 28th St., juried by Chrissie Iles, a curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art. It was interesting to watch her silently visualize how each piece would look, deep in thought, while the rest of us moved pieces from one wall and to another and then often back onto the original wall, at her request. She required the center of each piece to be exactly 57” above the floor, so I helped Bob Mielenhausen, a fellow Viridian artist, in measuring each one, then bisecting it with a little plastic dot sticker. We then held up each painting to align the sticker with a levelled mark running along the wall at that height. It was something I’d never thought to do before: having the center of every work at exactly the same height in relationship to the floor and the viewer’s eye. No doubt it’s the most elementary rule in the curatorial book, but it was nice to finally learn it. It really made a difference in the look of the whole show when we were done.

As all of this went on, Chrissie was sensitive to distractions. “I don’t want to see those phones,” she said at one point, referring to a diptych involving a cell phone and a more traditional handset. So I would move them out of her sight. Same with a couple other paintings that seemed to keep getting shunted off to some place out of view. I was beginning to feel their pain. I’ve been ostracized; I know what it’s like. Finally, though, she would hit on the exact spot for a particular work and up it went, never to be reconsidered. Those seemingly neglected phones, in fact, were the first to find their home, long before everything else in the show. But for a long time, it was, “Just move that one somewhere else.”

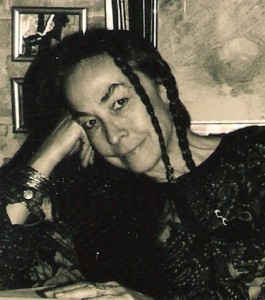

She specializes in film, as well as film and video installation, and Minimalist and process-based art of the sixties and seventies. She is part of the curatorial team formulating the overall artistic policy of the Whitney Museum. For our day’s work, I joined our director, Vernita Nemec, her assistant director, Lauren Purje, and Bob. It took us six hours, from start to finish, with an hour break for brunch at the Half King a couple blocks away, where you get free Bloody Marys with your meal, their tomato juice loaded with bits of shrimp and hot sauce. When Chrissie came back from a long phone call from Europe, she started telling us about her close friend, the legendary international performance artist, Marina Abromovic.

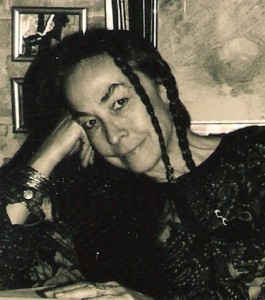

Chrissie Iles

“I’m currently writing the text for a book on her performances. I did her first retrospective at Oxford,” she said, giving us a lot of background about how close the Abromovic family was with Tito in Yugoslavia, before it broke apart along ethnic lines. “The key to a lot of her work was her mother. Really rigid woman. Really awful.”

I wanted to hear a lot more, but our conversation was kept short by her long conference call with Europe and the need to finish hanging the show. Whan we got back to the gallery, the level of care she continued to put into every detail of our group effort impressed me enormously. The work was of varying quality, with many well-realized pieces More

July 6th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Vernita N’Cognita

Vernita N’Cognita is heading to a 16th century castle in a little town near Frankfort, Germany next month for a new performance, with a partner this time, David Rodgers, and she’s trying to raise money for the trip through Kickstarter. In this evocative Old World location, they’ll explore the clash between the European past, with it’s traditions and rituals, and the 21st Century world. They’ll attempt to portray the conflicts and contradictions we all face on a daily basis. Their performances will be a mix of theater, music and dance.

The work will be called “Trail of Sighs and Whisper,” and will be as feminist as most of her work and, from the way she describes it, slightly mournful about the sadness of human relationships. She’ll perform at the town of Homburg, at the invitation of a university there. I first heard about the performance at the meeting of gallery members last week when Vernita announced: “I’m looking for a wedding dress. I’ll probably do bad things to it.”

Here’s how she described the project on her website:

I’m going to Homburg, Germany where David Rodgers & I are performing at the end of August for the Sommerakadamie of Kunst in Schloss Homburg, which is an annual art institute and creative gathering in the small town of Homburg-am-Main, in Bavaria, where Rodgers has been participating and performing since 2008. It’s called The Trail of Sighs and Whispers, a performance inspired by the ritual of marriage and the age-old tradition of “walking down the aisle”. In a twisted tale told through Butoh movement, costume and voice, I, The Bride, will take aim at this ritual of culture and seek to shed light on “The Wedding” and the difficulty of wedding the complex paths of two lives in the world of the 21st Century. Utilizing studies of Japanese Butoh, which I have practiced for over a decade, I will use masks and movement to create a work with feminist overtones. In this work, I will be using the streets and main plaza of Homburg as my stage, traveling by foot and bringing the audience to the entrance of the Church of St. Burkardus, where I will be joined by Rodgers as I finish my quest and he begins his. Our performances will be interrelated and collaborative, but conducted as individual performances. They will take place on Saturday, August 25, 2012, at 8 PM.”

Rodgers’ performance is called The Music of the Spheres. It dramatizes an imaginary encounter between 17th century astronomer Johannes Kepler and remarkable astronomical events of 2012, which he was able to predict mathematically in the 1600’s. The performance will explore how he reacts to finding himself 400 years in the future and learns to communicate his vital scientific discoveries to the people of the computer age. In this theatrical spoken-word performance, staged in the courtyard of the castle, Rodgers will work with local musician David Hartmann, who makes and plays all of his own unconventional musical instruments, providing the live soundtrack music to accompany Kepler’s journey through a new world.

Over lunch, on the day we put up the new juried show at Viridian, Vernita went into a little more detail on the spirit of this new work. “I’ll probably do some bizarre things along the way. I’m examining and confronting the underside of femininity,” she said. “All the things women do to make them who they are. I’m also exploring the impossibility of welding two lives together in this culture.”

She is preparing a Kickstarter project to raise money to cover the airfare to Germany and back for her and Rodgers. Other expenses they expect to cover themselves.

July 5th, 2012 by dave dorsey

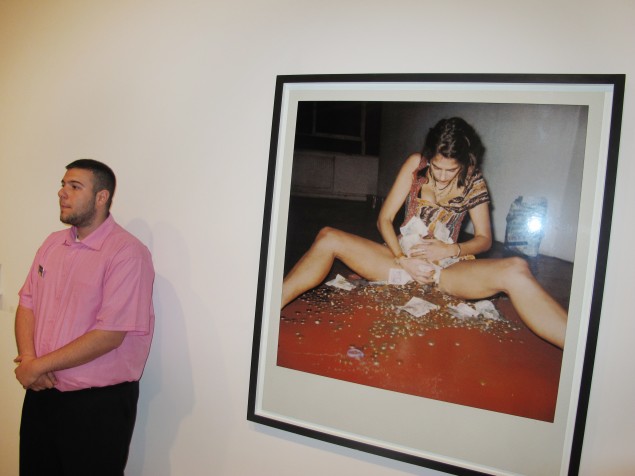

Natalie Frank, Portrait of S at Fredericks & Freiser

I got home yesterday from a busy four days in New York City. I rode my R1150R down and back, and took it over the upper level of the George Washington into the city almost every day I was there. Though it was very hot most of the time, for the most part, it was bliss, not only the ride down through the Catskills but also the feeling of being able to weave and carve an original path along any Manhattan street clogged with cars. There is no such thing as a parking problem for a motorcycle in New York City. You just back the bike between two parking spaces, or at the front of a row of them, and you’re good to go. (I did bolt a lock to the brake disk.) I learned a lot on this trip, not only about riding a thousand miles on two wheels in four days, but also about a couple artists I thought I already knew fairly well and a slew of others I didn’t know at all. I also learned some basic rules about hanging a good show from Chrissie Iles, a young curator from the Whitney Museum of American Art with a British accent I loved, who showed up on Sunday—just back from Spain—to direct us in our attempt to properly exhibit the summer show she’d jured for us at Viridian Artists.

More on that show in another post, but the most fun I had on my visit was a day I spent with John Lloyd, a Brooklyn artist who joined me for a tour through various Chelsea galleries. Our conversation about art is something I want to share, mostly because it’s what I enjoy most about visiting the city. All the talk. The conversations about art and life. He’s fun to be with, because his knowledge ranges over a number of disciplines, and he touched on only a couple. John and I were comparing work histories and we followed similar paths, in terms of our art. In college, we both came to the conclusion that we needed to do something other than make art to pay bills, and I didn’t want to teach. Mostly, I wanted to paint without anyone else meddling with my head. I wanted to do what came naturally to me, not mold myself into a “career” based on what work was being done successfully at the time. John said, “I never did the bohemian thing the way our friend Lauren is doing it. I wanted an income so I learned computers and went to work at the stock exchange.” That’s more or less what I did as well: I worked two years as a staff associate for the United Way, as a way of making rent money, and then went back to grad school for an English degree, but again decided I didn’t want to teach in departments where people had to name-check Derrida while doing some savage deconstruction of Little Women or The Great Gatsby. So I got a second master’s in communications and became a reporter. I kept painting, and now it’s finally becoming more central to who I am. I do not miss the bohemian stage of being poor and struggling at all. When I’ve stayed with younger friends in Brooklyn, sleeping on an air mattress, it isn’t for the romance of faux poverty: it’s a free way to stage my visits into Manhattan, that’s all. I’m not trying to live out my twenties again in some way I missed in the past. If I had friends in a $3 million house in Brooklyn More

July 3rd, 2012 by dave dorsey

Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, by Sargent

I’ve started another candy jar painting, part of a series I’ve been doing for several years now, off and on. This one’s a quarter the size of my usual work with these jars, which are a little over four feet by four feet. A while back, a friend at Viridian Artists, Bob Mielenhausen, suggested I try some of these in this smaller format, only two feet square, and so that’s what I’m doing, as a test, more or less. I’m also working on wood panel rather than on canvas or linen, as well as using a higher-quality paint—and I’m loving the changes—they’re teaching me a number of things about technique, but that isn’t what’s on my mind. What strikes me again and again about this series of candy jars, regardless of the materials I use, is how the results keeping reminding me of Renaissance painting. Feel free to say, Really, is that all? You and Michelangelo on the same page now? Lonely bloggers are allowed to make comparisons like this. It’s one of the perks of isolation. But that isn’t what I’m saying. I’ve never wanted to paint the way anyone did during the Renaissance—OK, that’s not true, because I’d give almost anything to paint nearly anything Bruegel painted, but I mean I’ve never attempted to adopt any methods or conventions from the Renaissance. I’ve never had the urge to paint one of Piero Della Francesca’s scenes. So I’m not entirely sure why the way I render a little oblong bit of translucent sugar reminds me of a Biblical scene from centuries ago. (It’s a coincidence that I’ve recently been reading about Italian painting from the 12th through the 16th centuries—and not because of any conscious connection between my intentions and what motivated painting during the Renaissance, but simply because I want to get into Vasari’s head, as a critic and historian.) Last year, this same similarity occurred to me. I remember looking at a previous candy jar I’d done, one that I exhibited at the last Halpert Biennial, and I thought that the loose way I’d painted some of the candy reminded me of Michelangelo. I know it sounds ludicrous to say this, but it was purely formal: the quality of the color reminded me of what the figures were wearing on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, and there were other connections: the clarity of line I can get with these paintings, and also for some reason the organic curves of these oval objects often remind me of parts of the human body—a length of someone’s arm, or a shoulder. More

June 19th, 2012 by dave dorsey

The Apparition to Brother Augustin, Giotto

Vasari’s The Lives of the Artists is an amazingly readable book, full of lore and wonderful detail about particular painters, even though it was published nearly five centuries ago. The author’s voice is as alive and vivid as a contemporary writer’s, and his enthusiasm for his subjects seems as if it ought to be a model for all art criticism, especially now. He wrote about human beings, in terms any commonly educated reader could grasp, and it’s clear why the reader should love the work he described. He wrote about what he admired, and his appreciation for the art he saw around him was boundless. The preface, amusingly, says that “in some respects Vasari’s vocabulary is limited. For example, he employs the adjective beautiful over and over again, much to the despair of all his translators.” It sounds less like a limit to his vocabulary than a sign that he adhered to the highest standards in what he treasured about art. There’s something ingenous and innocent in that little fact that he kept calling attention to the beauty of the work; it’s endearing. Tough luck for his translators, I guess, but great news for anyone interested in the Italian Rennaisance.

I ordered a used paperback of this book because I was eager to read about Giotto as much as any of the other painters in his dozens of biographical stories. I’ve always considered Giotto an austerely religious genius who initiated naturalistic depiction of individual human beings in Western painting. Instead, what seemed to emerge, while reading Vasari, was that Giotto advanced the depiction of the human figure as a necessity for conveying the reality of a human being’s inner life. He managed to show extreme human emotion in figures which lie somewhere between flat Byzantine icons and the full realism of the later Rennaissance. His work was almost exclusively devoted to Christian subjects, so when I came to learn how worldly he was, and how witty, it took some getting used to. He was a smooth, charming, totally at ease with anyone. His skills were legendary.

Vasari considers great draftsmanship as the foundation of visual art, a way of capturing More

June 3rd, 2012 by dave dorsey

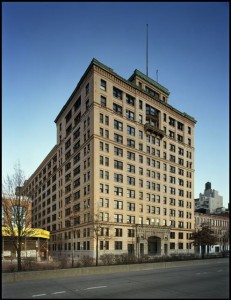

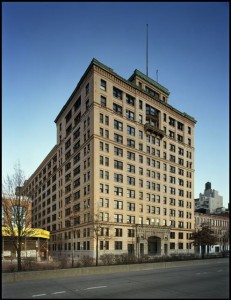

Westbeth, Greenwich Village

Nicely written reflection in the NYTimes this morning on the high-end art market from Adam Davidson, from NPR. Loved his last paragaph:

The value of any artist’s work is determined by an insider world of cultural arbiters who coordinate with one another. They know long before the rest of us which new artist is going to have a big show, who is going to be trashed in a review or whose piece was just sold privately for a small fortune.

Because the art market isn’t regulated like financial securities, insider dealing is generally not illegal. In fact, being a truly influential insider is so rewarding that the slots are zealously guarded. Larry Gagosian, perhaps the world’s most influential gallery owner, needs a nearly impossible combination of skills — deep art knowledge, master salesmanship, charm, ruthlessness, financial savvy and the respect of the artists themselves — to maintain his edge and root out competition. When you start a consulting service or invest in an art fund, you are an outsider seeking to make money in a shadowy market filled with brilliant insiders just like him. No wonder it rarely works.

As I talked to art advisers and economists, I kept thinking of my childhood in Westbeth, a subsidized housing complex for artists in Greenwich Village. Our neighbors, painters and sculptors among them, were decidedly not rich. To them, the very idea that art should make someone wealthy was laughable, even offensive. It makes me happy to think that this world of art-as-investment is a minuscule fraction of the art world overall. Most people who create, trade and own art do it for a much simpler reason. They just like it.

May 31st, 2012 by dave dorsey

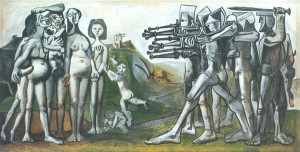

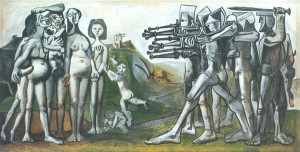

Picasso's Goya

I got two thoughtful responses, via email, to my posts about Arthur Danto. Rick Harrington reacted as a practitioner suspicious of theories divorced from the actual practice of art. I agree that theory ought to arise as a response to art, not the other way around. (Tom Wolfe, in The Painted Word, suggested that in the middle of the 20th century, criticism began to be the basis of a lot of art, rather than a response to it—and, as conceptual art began to emerge, his notions seemed to be confirmed. Art can often becomes little more than the illustration of an idea. Once you understand what’s being conveyed, you’ve exhausted the act of looking at it.) Yet Rick is saying something more practical, that an artist creates out of a struggle to make a work of art in a certain way, physically and emotionally, and if that means working in ways artists from previous eras have worked, then it’s a perfectly vital way to create art. To prohibit any attempt to immerse oneself in past art and internalize it, and even to try to create art in the same way as previous artists, seems like hubris on the part of a critical theorist. To say it’s pointless to paint as Caravaggio painted, using his techniques, would ignore the work of an artist who might have something illuminating to offer by doing just that. Superficially, the work might look anachronistic, yet it might also seem alive and rich because of that. Dave Hickey, in The Invisible Dragon, talks about distinguishing what an artwork embodies, in its formal qualities, and what it denotes or signifies—the meaning a work of art assumes in one age can be transformed when future generations look at it with new eyes, but what remains the same, and what enables it to endure, is what it embodies, the craft and physical qualities of the work that continue to convey the same indefinite energy and awareness to a viewer. Great work stays alive from one era to the next, precisely because of its formal qualities, not because of what it is assumed to mean. In other words, the work’s beauty survives its ostensible significance to a particular generation. And because of that, a new generation can find new “meaning” in the image. I think Rick is suggesting something similar. Danto, it seems to me, equates the forms of previous art with their meaning, as if a Byzantine mosaic must mean only one thing to a viewer, and was most meaningful only within a certain historical period, and has no value whatsoever to a 21st century Buddhist, say. Rick says, More

May 30th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Pablo, Yan Pei-Ming

David Zwirner’s gallery is first on my list whenever I’m in the city, and he rarely disappoints. His current show, Black Paintings, by Yan Pei-Ming, expands this Chinese artist’s ambitions, which until now seem to have centered mostly on large-scale portraiture. He was unable to achieve an education in art in his native China, and he moved to Paris to study painting, where he has remained and has found himself swept into international art fairs, high-priced sales for his work at auction, and even a small conceptual-looking installation of his paintings at the Louvre. Nice work if you can get it. In 2009, he exhibited his portrait of Obama at Miami Art Basel. Last year, his portrait of Mao sold for half a million pounds in London, with bidders from 11 different countries. And only a few days ago, Zwirner unveiled Yan’s portrait of Lady Gaga at the Hong Kong International Air Fair. Hey, nobody’s perfect.

With this new show, Yan’s reached much further than before, and he’s succeeded. These heroically scaled paintings—they feel as wide as a movie screen—are done in his typical grisaille, and in this new show he’s taken the values down into Tonalist territory, as dark as you can get and still depict something, with subjects almost obscured by the enveloping gloom. His vigorous brushwork brings to mind Lucien Freud, Natalie Frank’s portraits, even Jenny Saville, if she traded her flesh tones for oils pigmented with charcoal. Ostensibly inspired by Goya’s late wall paintings, which include visionary scenes and nightmarish depictions of horrific and occult subjects, these paintings seem even more liminal than the Spanish master’s. Up close, you recognize almost nothing but an impenetrable ocean of paint, and it’s a rough, choppy ride for the eye, from any angle. But the further back you stand, the more the images slowly resolve into life. The artist’s previous work has had political overtones, and it’s present here in Ghadhafi’s Corpse and his near-copy of Goya’s Execution and even in his apocalyptic painting of crows, if you look long enough to recognize the setting. Yet the Goya pastiche reproduces that collective murder in a void, with no indicators of time or place. The three paintings that form the heart of this show seem to take his anxieties to a spiritual precipice: his portrait of Picasso as a penitent young man, a depiction of a lifeboat adrift at sea, and a storm of crows swirling and darkening a night sky in Athens. All Crows Under the Sun are Black! feels like a scene Hitchcock might have crafted for his version of the Book of Revelations: oppressive and inexorably foreboding. The end of something enormous is at hand, or the beginning– Democracy itself (depending on where you live) given the Parthenon tucked into shadow under that sky. The horror he shows you seems near and alluring in a weird way and maybe is an expansion on his image of the Arab Spring. You want to slip into that image and find a place to hide, or participate. In Moonlight, he seems to have offered a slightly more hopeful version of Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa, a lifeboat tossing in the sea with the beacon of an oncoming rescue vessel on the horizon. It’s oddly uplifting, unlike its predecessor, which feels like a melodramatic summer blockbuster by comparison. With his portrait of Picasso, he’s envisioned the artist as a young man on his knees, his head bowed, apparently dressed for a ceremony, obedient and humble. It’s the most interesting image in the show. This legendary alpha dog of visual art is posed as a servant or vassal or devotee; and this is a man who probably represents for most of us the paradigm of the artist as a someone who lives by his own rules, governed only by his self-assertive male prerogatives. Instead, Picasso here is seated on his knees in a supplicant pose, hands placed carefully on his legs, his gaze averted, as if he’s waiting for instruction or an inner rescue or blessing. These paintings are as large as anybody’s ego, yet that spectacular scale is undercut in every way. The images are vulnerable and understated, with a reverence for uncertainty and the unknown, and they offer only enough information for the imagination to do most of the work. They feel like an almost unwilling personal exposure: exactly the way Goya’s Black Paintings did, meant only for his own eyes and no one else’s. These few images, together, have a tremendous impact, both emotional and imaginative, and as black as they are, they aren’t oppressive, but thrilling. They balance horror with a life-affirming awe, and the despair they seem to embody has to contend with a far more interesting and artistically defiant note of transcendence.

May 29th, 2012 by dave dorsey

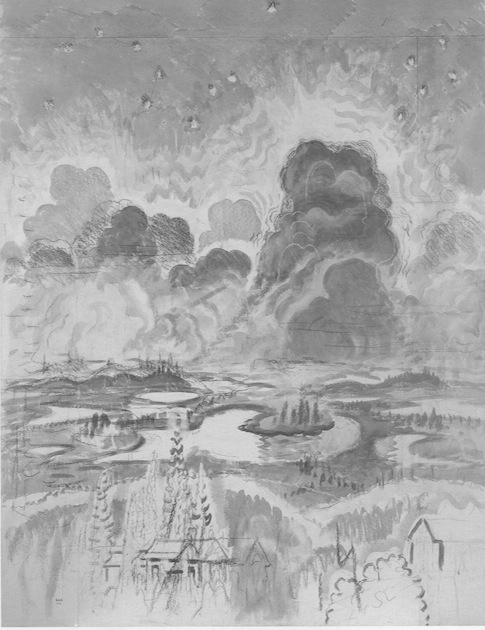

Heat Lighting, Charles Burchfield

Having just finished rereading After the End of Art, by Arthur Danto—I quoted from it in my previous post—I remember why I had such mixed feelings about this book the first time I read it. The history of art is over, and we’re now free to do anything we like. That seemed to be his vision, through most of his book. If a work is visible, it can be considered art. So anything is possible. Yet, in his last chapter, he suddenly lowers the boom and says that yes, visually, anything goes, but that doesn’t mean that we’re free to do anything at all. Essentially, you can work with styles and tropes from the past, but you have to put it all in brackets: it has to be ironic. If it looks exactly like a Rembrandt, and it was painted last year, call someone for some emergency deconstruction. Namely, someone with Danto’s credentials.

The sense in which everything is possible is that in which all forms (of visual art) are ours. The sense in which not everything is possible is that we must still relate to them in our way. The way we relate to those forms is part of what defines our period . . . one can without question imitate the work and the style of the work of an earlier period. What one cannot do is live the system of meanings upon which the work drew in its original form of life. Our relationship is altogether external, unless and until we can find a way of fitting it into our form of life.

That last phrase sort of opens up all the possibilities again, in a sneaky way: “unless we can find a way of fitting it into our form of life.” Well, duh. These passages I’ve quoted above strike me as incredibly awkward attempts to dance around the phrase “form of life” as a way of remaining true to the postmodern orthodoxy. There is no universal truth; there are no eternal verities in human life. We’re all simply living through a period in which fleeting cultural forces have shaped our behavior and thinking, and we need art that addresses these temporary economic, social and sexual realities, unique to our time, until they are gone and the work we’ve done becomes a fading way of making sense of our “form of life.” So, Danto at first says that history is essentially over, for art: artists are liberated to do absolutely anything and call it art. (Whether it gains cultural traction through the respect and admiration of others is another question.) Yet then he reverses himself and says artists can’t simply make art the way previous artists did, because that “form of life”—ancient Athens, say, or Renaissance Italy or ancien regime France—no longer exists and the art of that period represents its own matrix of meaning that has no application in our postmodern world. In one More

May 26th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Arthur Danto

My friend and fellow painter, Jim Mott, once asked Arthur Danto if it was okay to paint landscapes again. It makes me laugh to write that, and I’ll bet it made Danto laugh to hear it, or at least smile. I don’t think Jim seriously thought he needed Danto’s permission, but he got a nice and predictable reply: “Yes, it’s okay to paint landscapes again.” Or do anything else and call it art, for that matter, as Danto points out in After the End of Art. Jim also got a bonus observation from Danto that Jim’s project as an itinerant artist was also a bit of performance art, with the landscape painting as only one element of the endeavor. It isn’t every day you get a favorable comment on your work from Arthur Danto. Or any day, for most of us. One passage from the book I just mentioned stands for me as justification for what I do as a painter, in the way Danto’s reply to Jim’s query works as an argument in favor of what Jim does in his painting. The passage I’m posting here ofers a wonderful, concise overview of why the pursuit of the New in art makes no historical sense anymore, though the experience of seeing with new eyes will always remain, for me, the goal of painting:

The history of Western art divides into two main episodes, what I call the Vasari episode and what I call the Greenberg episode. Both are progressive. Vasari, construing art as representational, sees it getting better and better over time at the “conquest of visual appearance.” That narrative ended for painting when moving pictures proved far better able to depict reality than painting could. Modernism began by asking what painting should do in light of that? And it began to probe its own identity. Greenberg defined a new narrative in terms of an ascent to the identifying conditions of the art, specifically what differentiates the art of painting from every other art. And he found this in the material conditions of the medium. Greenberg’s narrative is very profound, but it comes to an end with pop, about which he was never able to write other than disparagingly. It came to an end when art came to an end, when art, as it were, recognized that there was no special way a work of art had to be. The history of art’s quest for philosophical identity was over. And now that it was over, artists were liberated to do whatever they wanted to do. Paint lonely New England houses or make women out of paint or do boxes or paint squares. Nothing is more right than anything else. There is no single direction. There are indeed no directions. And that is what I meant by the end of art when I began to write about it in the mid-1980s. Not that art died or that painters stopped painting, but that the history of art, structured narratively, had come to an end.

May 16th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Luis Gonzalez Palma

May 16th, 2012 by dave dorsey

My good friend Donna Rose at artbrokerage.com sent me a link to a wonderful interview with her favorite art teacher, Fritz Scholder, who died a few years ago. It ranges all over the place, and it’s all refreshing. Some samples:

- All kids draw. I never stopped. I was real shy, and all I wanted to do was stay in my room and draw, so I wouldn’t have to deal with people. This, at the time, was difficult. But in retrospect, I always knew what I had to be. There was never any question. It was all that I could do. Plus, I was a rebel, right from the beginning. If someone told me to do something, I’d do the opposite. So I was, in a way, a bad boy in school . . . . You have to realize that at times art was really pretty foreign. For most people, an artist meant going to Paris and starving in a garret. No one was making a living in this country, except for Georgia O’Keeffe and Thomas Hart Benton. And so, what one did was to get degrees and teach at a university, and if you were good, you might be able to get an artist-in-residency. So, it was pretty bleak to think that you could be an artist.

- Picasso would paint way into the night. He’d wake up at two in the afternoon, and he always woke up grumpy. Françoise Gilot had to be there when he woke up and hear the same litany every day. “Oh, I feel terrible! It’s a terrible day. I have no friends. Matisse hasn’t written to me.” And he would go down the line. More

May 15th, 2012 by dave dorsey

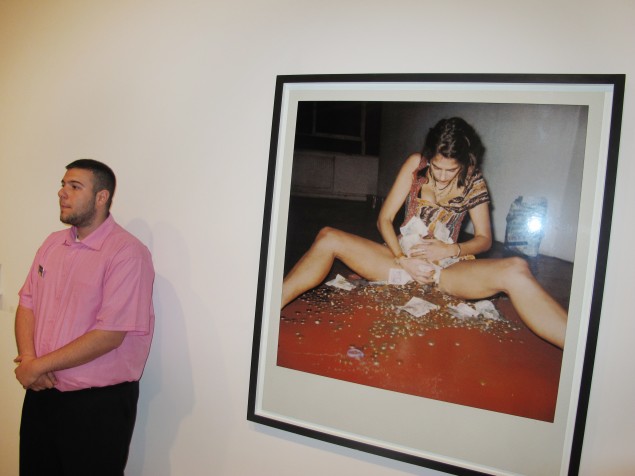

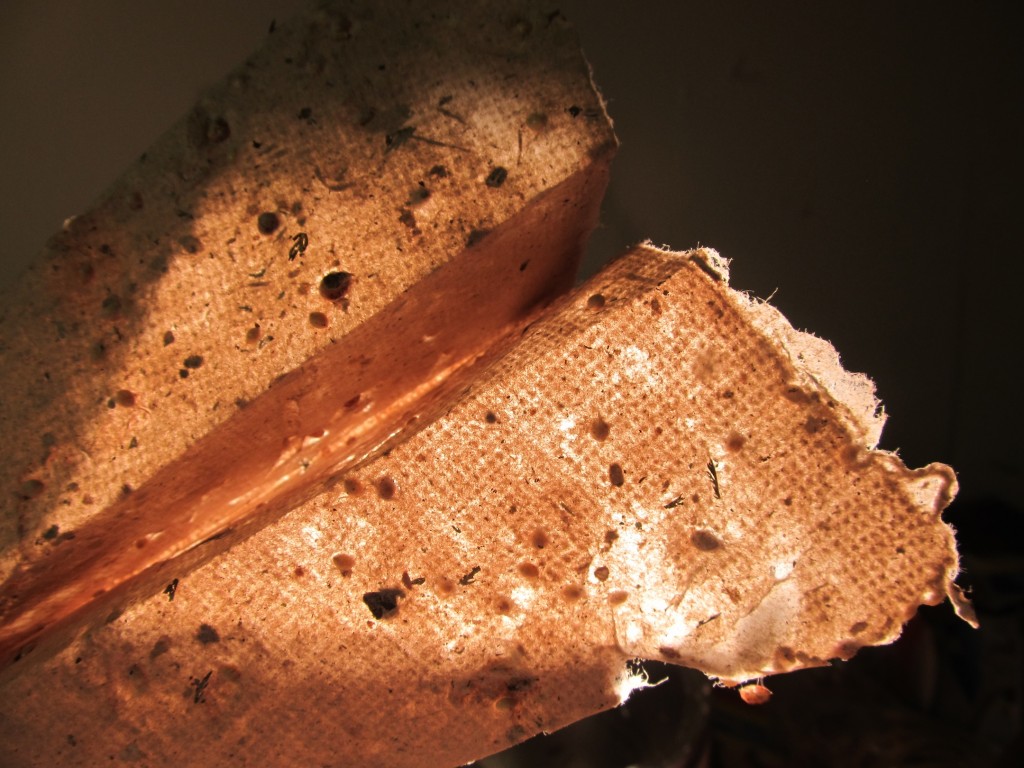

My seed-laden airplane in the Finger Lakes

As I sit in our family room with the laptop, I watch robins and chickadees land on our brick patio to gather bits of burlap and downy seeds and fibers from temporary flowerpots, and then fly off to build nests. We’ve got a lot of nests in our yard this year, and two catbirds yesterday were opening flapping around in our birdbath, which I’ve never seen before in the two decades I’ve lived in the Rochester area. Normally those slender gray birds are secretive, shy and usually stick around enough for only a quick drink.

It’s been looking like a great year for birds around here, so that’s partly why, yesterday, I drove down into the Finger Lakes, and found my way to an overlook above one of the gorgeous valleys that surround the Canandaigua area, about an hour south of where I live, and I tried to launch some of Jennifer Wenker’s paper airplanes into the great wide open of a sunny spring day. She’d made the paper by hand, impregnating the pulp with wildflower seeds. I’d been hoping to film the slow descent of my aircraft to the bottom of the valley, but the wind—as I’d feared—was not going to let it happen. Not matter how I aimed them, they made a sharp turn and headed north or south, along the line of the hills, or else they did a U-turn and flew back over my head. One made it far enough down to do the job it was made to do—dissolve in the rain and let the seeds drop into the soil and germinate. Ultimately maybe a few of the seeds will provide food to birds in the area. That the idea, anyway.

It happened to be the morning of Mother’s Day when I did all this, and I hadn’t thought of it at the time, but the act of launching these seeds was a mothering thing to do: trying to offer food to smaller, more vulnerable creatures. It was also my first act as a performance artist. In a way, Jennifer’s project is an open-ended invitation for anyone to become a conceptual/performance artist on behalf of the environment. She makes the paper. But it’s up to you to fold it into an airplane and sail it off toward some receptive patch of soil where it might grow into food for birds whose resources for nutrition grow scarce in places where farming and lawns and human landscaping have taken over. Jennifer made the airplanes as a project to complete her MFA at University of Cincinnati this year. She was inspired to create this campaign in response to a USDA program for poisoning “nuisance birds”: “Bye Bye Blackbird” in which, she says, 2 billion birds were poisoned in 2009.

My attempts to get planes to fly accurately into places where their payload could sprout taught me a few things I’m sure Jennifer had in mind when she hatched this project. First of all, you become aware of how resistant the land is to any incursion of new life, at least when it’s the cargo of small triangular aircraft. It gets stuck in the little twigs. It flips around and lands on gravel. It snares in tall grass. Most of the soil is already occupied—and a sunflower or thistle seed has to be lucky to drop into a tiny patch of available, sunlight topsoil. And that was in the wild of a New York State park. I came home and decided to aim another plane directly into a berm in our backyard where all sorts of untended and usually unwanted things will often grow. But it was, proportionally, a very small area in what is essentially a homestead packed with grass, flowers, trees, or mulch. Even so, plants still appear where I least expect them. I see how seeds can find places to grow on their own every year: strawberries that pop up in the brick walk to our front door—somehow having made their way from behind the garage—or new Shasta daisies three or four feet from the parent cluster. And the weeds always find a way. But the welcome volunteers are few and far between. More than anything else, this project has shown me that I had to drive quite a way to find a place open enough for the seeds I was offering. The closer you get to home, the more you realize how other forms of life often have to find a way to live despite the presence of people.

May 14th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Rush Whitacre

Next week, I’m going to visit Brooklyn one more time to help Rush Whitacre load up his pickup and head back to his home and studio in Ohio. He’s had his fill of New York City. I’ve gotten to know Rush well since we met last summer. He offered the use of his truck to Viridian Artists, where I show my work, when the gallery moved to its new location on 28th St. in Chelsea. He had me laughing that first day, and he’s kept me laughing every time we’ve met since then. I’ve described him before: tall, massive, with blondish-brown hair and a cropped beard. He wouldn’t have looked out of place sitting next to Joe Namath in a lounge somewhere back in the 70s. Yet Rush doesn’t pretend to convey that kind of cool: he’s a guileless hugger, who brings out the nicest qualities in the other people around him, always trying to make someone else a little happier while he’s around. (Often, this involves the consumption of beer, though not always.) In a way, his entire approach to life is anti-Cool. He’s extremely intelligent, and yet he doesn’t impose any of it on anyone else. Just before his move to Brooklyn, he finished his Ph.D. in fine arts at the University of Cincinnati and, as I’ve pointed out before, he has a total of five college degrees, including ones in biology and bio-chem. He’d rather come across as the happy, enthusiastic midwestern country boy who listens to Taylor Swift and paints huge sunflowers without a whiff of postmodern irony.

I’m disappointed that Rush is leaving, but I don’t think he came to the city in order to break into the art scene. He seemed to be using his year to absorb as much art as he could and return with a large inventory of memories and photographs for teaching back in Ohio. On my last visit I let him use my Nikon D40, and we plowed through most of the galleries at the Metropolitan, where he shot nearly 300 images for use as teaching aids if he gets the job he hopes he’ll land for More

May 13th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Being a painter generally means feeling like an object of curiosity or affectionate sympathy—I do admire his work, love the guy, but how does his wife put up with him? Sometimes I think I’m looked upon with vague suspicion, as if my street’s property values will immediately edge down if word gets out about what I do with my time. Making a painting doesn’t strike most people as work. It’s fundamentally irresponsible, usually requiring other sources of income, and is essentially a strenuously sedentary form of play. Like, say, high-stakes poker. No sweat is involved, but money can be made, though not very often and only by a few of the luckiest practitioners.

There are other problems. Those of us who devote long hours to the act of painting tend to hang together, forming little suspect coteries of marginality—grown men and women who want to make pictures, dress in age-inappropriate ways, or gender-inappropriate ways, or species-inappropriate ways, and usually earn less than enough to make ends meet. We look at one another and think, yep, she has the disease too, thank God, because it means I’m not alone. I see Richard Dreyfuss sculpting a mountain with his mashed potatoes at the dinner table in Close Encounters of the Third Kind, as his children weep with the conviction that daddy has gone bonkers, and I say, Keep going, keep going, Roy, it will all make sense in the end! But I wonder. Will it? So I hang out with fellow artists and drink beer and talk about how badly other people handle their paint, or how amazing Richter is when you see his actual canvases, or how so-and-so is a clever sell-out—and in the end we go our separate ways and feel more energized, but just as alone. Because the solitude is essential, even if sometimes intolerable. You have to isolate yourself and work on self-imposed deadlines for a solo show where months or years of labor may go up and come down with only one or two sales, no reviews, and maybe much less praise than you’d hoped to get. And then, after these necessary bouts of doubt and loneliness, you rush to hang out with other artists again and talk your way toward 3 a.m., hoping that the friendships will support you, emotionally, until you arrive More

May 5th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Not sure what, or if anything, all those little figures mean–or how many Chinese workers it took to make them, probably–but this is just cool, even though that fed-up Ph.D., whose rant I liked a lot, in my previous post might question whether or not it’s worth anything as art. More Gormley work at http://www.mymodernmet.com/profiles/blogs/remarkable-geometric-human-figures and http://www.mymodernmet.com/profiles/blogs/antony-gormley-field.

May 4th, 2012 by dave dorsey

From “I’m Sick of Pretending. I Don’t Get Art.” from someone with a Ph.D. in art:

“You know what? I’m sick of pretending. I went to art school, wrote a dissertation called “The Elevation of Art Through Commerce: An Analysis of Charles Saatchi’s Approach to the Machinery of Art Production Using Pierre Bourdieu’s Theories of Distinction”, have attended art openings at least once a month for the last five years, even fucking purchased pieces of it, but the other night, after attending the opening of the new Tracey Emin retrospective at the Hayward Gallery, I’m finally ready to come out and say it: I just don’t think I “get” art.”

Read the rest here: http://www.vice.com/en_uk/read/im-sick-of-pretending-i-dont-get-art

April 30th, 2012 by dave dorsey

A shipment of small, light aircraft arrived at my door yesterday in Pittsford: a dozen sheets of hand-made paper impregnated with wildflower seeds. I will fold them into airplanes and then “return them to flight” wherever I can find a place they might actually germinate. I know exactly where I’m going to set at least one of these birds free, maybe all of them—from a promontory in the Finger Lakes near Bristol—and I’m betting that nobody else is going to get the hang time I’ll get, if the wind is at my back anyway. (I’m a guy, so I think everything’s a competitive event, even if I’m totally alone . . .) But I also want to try for an urban area or two, maybe Central Park when I’m in New York in a few days, or Brooklyn.

Jennifer Wenker made the airplanes as an art project to complete her MFA at University of Cincinnati this year. She was inspired to create this campaign in response to a USDA program for poisoning “nuisance birds”: “Bye Bye Blackbird” in which, she says, 2 billion birds were poisoned in 2009. I met her on a swing through her school with Rush Whitacre on my way to Louisville recently. So now I have a stack of wonderfully pebbly sheets of paper, some with wildly random deckle edges, and my next step is to turn them into planes.

I love this project because I love birds, and planting things, and the unassuming childlike simplicity of the whole project. The image of the airplane, the concept behind the project—it’s all tremendously simple, yet loaded with poetic resonance. As Jennifer put it: “We’ve taken over so much of the landscape, it can be hard to find a place where seeds can More

April 24th, 2012 by dave dorsey

In a fine article in The Brooklyn Rail about pursuit of spectacle and the influence of money on art, Dore Ashton quotes Friedrich Nietzsche:

Far from the market place and from fame happens all that is great: far from the market place and from fame the inventors of new values have always dwelt.

April 12th, 2012 by dave dorsey

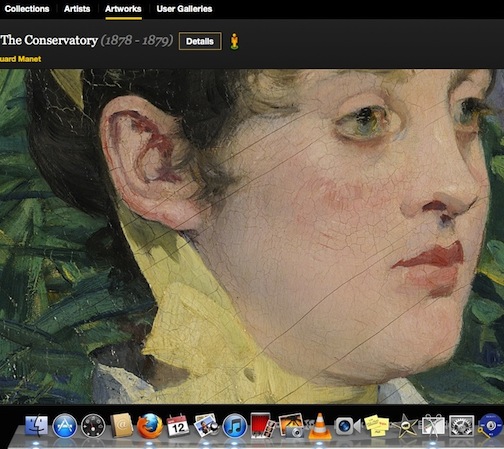

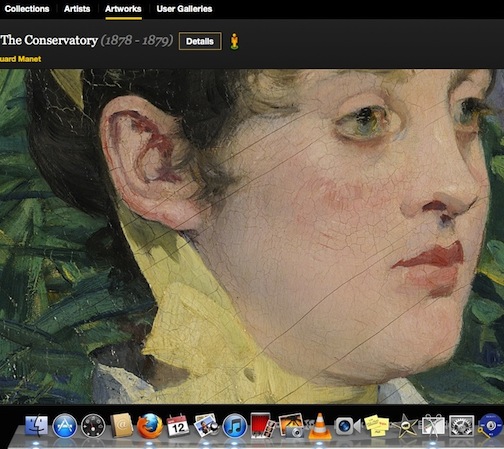

Screen grab of Manet zoom

I’d forgotten the Google Art Project existed until I read Roberta Smith’s celebration of it in the NYTimes just now, on-line. It has expanded considerably since last year, and though I don’t think this is going to suck as many hours out of my life as Halo has, over the years, it could be a contender. It’s frustrating to read how resistant many museums and rights-holders continue to be, given the potential for total access this project could offer to nearly anything and everything ever painted–and what a gift that would be to nearly anyone interested in art. Painting is meant to be seen, not stored away in private rooms. The sad reality of art, in general, is that the public has access to only the tiniest tip of the iceberg. Of work that’s been done over the centuries, the vast majority sits in vaults or in places only few can access–it’s as good as gone, a sea of unreachable, unknowable dark matter for most of us. Those rights-holders who continue to stand aloof from the Google project should bear in mind that there continues to be no substitute for actually standing a few feet away from a work of art: no reproduction can fully capture what you see by looking at the living, physical object. I spent years scratching my head over Bonnard’s critical standing until I turned a corner at MoMA and stood before one of his surfaces, astonished. And I’ve also felt deflated looking at work that thrilled me in books or on the web, only to see how clumsily the painter actually handled the medium. Yet if my quick sample of Google’s project is any indication of its potential, it could come pretty close to the experience of seeing the actual work, and this would be an enormous boon to both artists and scholars. When I went to this site this morning, I clicked on the first image that appeared, Manet’s In the Conservatory, and double-clicked to zoom a little closer. Then I did it again, expecting blur or those squiggles of photographic compression. Yet the image stayed crisp. Again, I clicked, with no loss of resolution. By the time I was done, I was as close as a kiss to this lovely model’s face. Nothing but her cheek and lips filled the screen–a pleasant prospect in and of itself, but it also showed me the actual surface of the canvas so distinctly I could make out how the thing had been rolled for storage. The diagonal cracks in the oil paint clearly showed that someone had removed it from the stretcher and rolled it, starting with the point of one corner and ending at the opposite one. I don’t especially need this information, but someone else might, and yet what I do want is to see the quality of his paint, the perfect, delicate skin tone, the evidence, yet again, of Manet’s seemingly cavalier brushwork, all the effortless mastery so clearly there in every square inch of his best work. So bring it on, Google. Get it all on-line. Everything. Picasso! Braque! Artists I’ve never heard of. Right now, I am Gary Oldman in The Professional, crazed and, well, frankly a little goofy with bloodlust, telling his henchman: Bring me everyone.

Whataya mean everyone?

Oldman roars: EVERYONE!