Archive Page 41

June 27th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Parquet Courts delivered. Sadly, the Post Office didn’t.

Represent is about the painting life. It says so up there on the banner. As of today, it’s also about shipping, which is a crucial part of the painting life (if you care to show your work to other people in a public way.) Mostly, over the past two years, I’ve been writing about the painting part, and not much about the life. So I’m going to correct that with a lesson on how not to attempt something absolutely essential to this pursuit: frugality. It’s always a good idea, in any field, to spend as little as possible, but especially as an artist. With that in mind, it would seem a no-brainer that I shouldn’t vacation in, say, Palm Springs. Or play golf. (Or visit New York City for that matter. You know how much parking costs in Manhattan? I don’t have the heart to tell you.) But if both your kids live and work in L.A., and you get to see them once a year when they come home for Christmas, going to L.A. for a week in the summer is the best option. This is because it’s exceedingly hot in the desert in July, when rounds of golf and rental homes are as inexpensive as they ever get there. During July, it would cost more to golf at many public courses here in Rochester.

So we save up my wife’s earnings from teaching second grade, and we spend a week with our kids in Palm Springs (much less expensive, actually, than staying virtually anywhere closer to L.A. itself), during one of the hottest weeks of the year. A round of 18 holes at Indian Canyons Golf, where my son Matthew and my son-in-law, John Bridge, and I will be playing every morning during our annual week in Palm Springs, costs $45 for eighteen holes, per player, unless you buy a summer discount card for a one-time fee of $65, which lowers the greens fees to $30 per person, every day, for the six days we play. A couple hundred dollars of savings! Beautiful. I’m a painter so, as you know, I can find the beauty in many things, including a vacation where the daily high will be 115.

Which brings me to the subject of the U.S. Postal Service. I know, that’s a pretty bumpy transition, but it will make sense if you stay with me. MORE

June 24th, 2013 by dave dorsey

In Pakistan they paint actual trucks and consider it art, as they should. They also paint billboards as an art form. Mahwish Chishty imagines, in her paintings, this tradition applied to drones. Mother Jones asked her:

In Pakistan they paint actual trucks and consider it art, as they should. They also paint billboards as an art form. Mahwish Chishty imagines, in her paintings, this tradition applied to drones. Mother Jones asked her:

MJ: So has the Department of Defense asked you to repaint any of their Predators yet?

MC: [Laughs.] No, but I was thinking that would be so cool. I probably should put in a proposal for that.

June 21st, 2013 by dave dorsey

Night Sky in Nevada

If you’ve got six hours to spare, this is what it looks like to sit in rural Nevada and gaze at the stars. You can see them just starting to appear in the post-sunset sky here. Warhol wishes he’d done this. Full disclosure: I watched about 30 seconds. Click to YouTube to see any or all of it.

June 18th, 2013 by dave dorsey

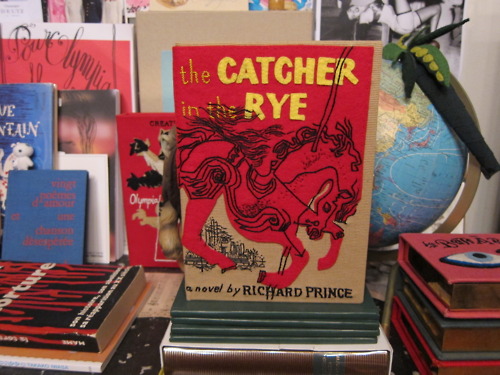

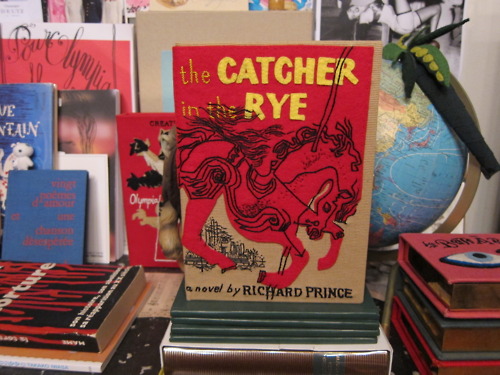

Catcher In The Rye, facsimile plagiarized first edition, Richard Prince, $62.

Warhol shrugs.

“Richard Prince has been in the news a lot lately for his courtroom battles against the laws of copyright as they apply in fine art. Some have even suggested that Prince’s courtroom behavior—ambivalent responses to simple questions about his work—is the latest stage of the artist’s protests against authorship and authority.” —Interview

The courage! Protesting the tyranny of authorship! Oh so postmodern. Isn’t the disappearance of the common reader and the death of the mid-list book enough? The Koran might look nice with Prince’s name on it, but he should check with Rushdie first. (Anyone else think the last Sonic Youth album was so more compelling than this interview?) Someone recently told me, “The internet is a beautiful and complicated web of glittery bullshit.” Sometimes it’s beautiful, sometimes not.

June 16th, 2013 by dave dorsey

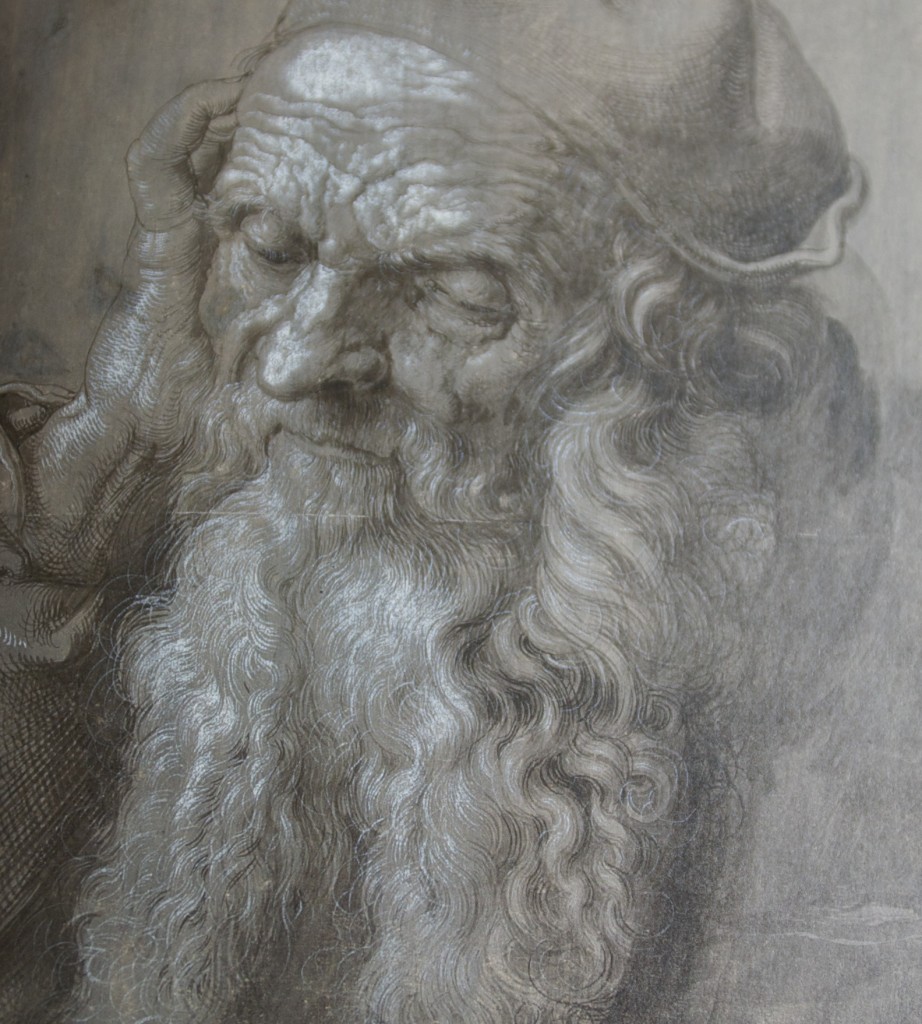

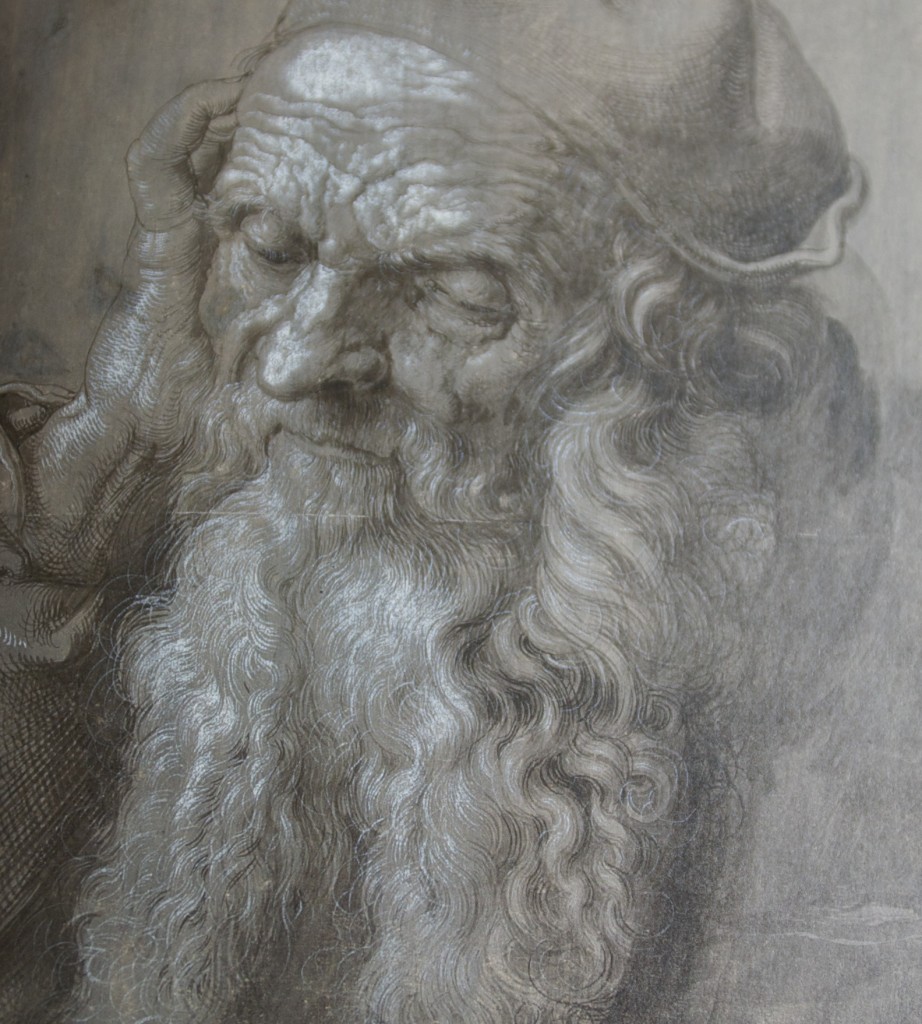

Detail, An Elderly Man of Ninety-Three Years, Durer

A week ago, I drove six hours, due south, from Rochester and arrived at the National Gallery during the final afternoon of the Durer exhibition in Washington, D.C. It would be a bit of an understatement to say a glimpse of some of the greatest art ever created was well worth the zigzag navigation of Pennsylvania’s state highways. Being able to stand a foot or two away from some of this work, from Vienna’s Albertina Museum, was a profound experience, and I walked away from this magnificent show with a much deeper awe over Durer’s genius. He may be the greatest draftsman who ever lived, not simply because of the accuracy and versatility of his representational skill—how true he could be to the way ordinary things actually look—but also, paradoxically, because of the idiosyncratic, obsessive extremity of his images, which always seem to convey something infinite and unknowable, even in the depiction of commonplace things. I’d be hard-pressed to think of any work of the Italian Renaissance that could compete with the intricate precision of Durer’s line.

It’s no accident that this exhibition focused on prints, drawings, and watercolor paintings—which, with Durer, are really drawings with color. His heart and soul, as well as his income, were in his drawings, not his oils. The show made clear he had a preternatural ability to reduce everything to line, especially when, standing close to one of his surfaces, you recognize that even when he was ostensibly “painting” on paper, he was often using parallel lines—as if he were doing an etching—to indicate shade. He established areas of mid-value simply by drawing straight or wavy lines, perfectly aligned and equally spaced, thick or thin, depending on the level of gray he wanted to evoke. Standing before some of this work, it’s hard to believe he could have done it without some kind of mechanical guide to steady his hand—the lines are so perfectly executed and uniform.

When Durer traveled to Italy, Giovanni Bellini refused to believe the artist could do what others said he could until he saw Durer demonstrate it. He asked Durer what tiny brushes he used, with multiple hairs that would produce the wavy parallel lines in his depiction of hair and fur and shaded areas. Durer showed him the ordinary, single-pointed brushes. “No, I don’t mean these but the ones with which you draw several hairs with one stroke; they must be rather spread out and more divided, otherwise in a long sweep such regularity of curvature and distance could not be preserved.” Nope, these are the ones, Durer said. Prove it, Bellini said. So he did. As Bellini later said, “Taking up one of the same brushes, he drew some very long wavy tresses such as women generally wear, in the most regular order and symmetry.” As a second observer recalled, “No human being could have convinced Bellini by report of the truth of that which he had seen with his own eyes.”The exhibition catalog expresses the same thing perfectly about MORE

June 15th, 2013 by dave dorsey

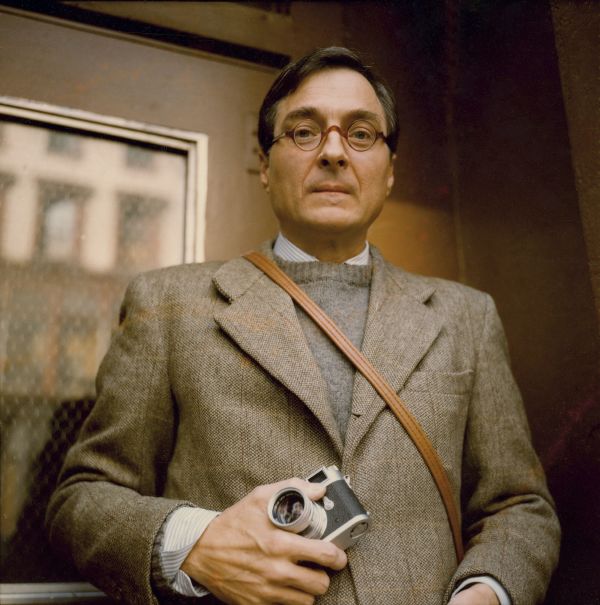

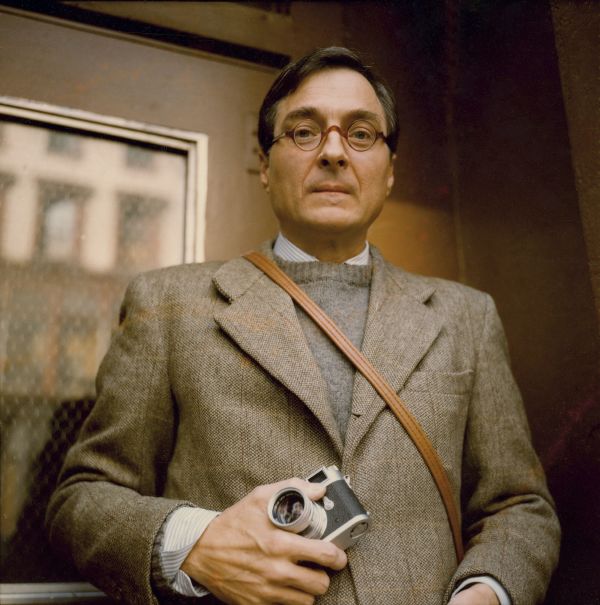

William Eggleston

From patriksandberg.com:

Drew Barrymore: How do you feel about cropping?

William Eggleston: I don’t.

DB: Thank you! Cheers. God bless you. There’s a part of me that feels like it’s not fair.

WE: You’re right, it’s not. It’s messing with things. There’s something sinister about it. When it’s cropped that’s not you anymore. So that’s one reason I don’t do it. Another reason is just one of those personal disciplines. I might have picked it up originally from [Henri-]Cartier [Bresson], who was a fanatic of never cropping. You know, I had a meeting with him, one in particular, it was at this party in Lyon. Big event, you know. I was seated with him and a couple of women. You’ll never guess what he said to me.

DB: What?

WE: “William, color is bullshit.” End of conversation. Not another word. And I didn’t say anything back. What can one say? I mean, I felt like saying I’ve wasted a lot of time. As this happened, I’ll tell you, I noticed across the room this really beautiful young lady, who turned out to be crazy. So I just got up, left the table, introduced myself, and I spent the rest of the evening talking to her, and she never told me color was bullshit.

June 14th, 2013 by dave dorsey

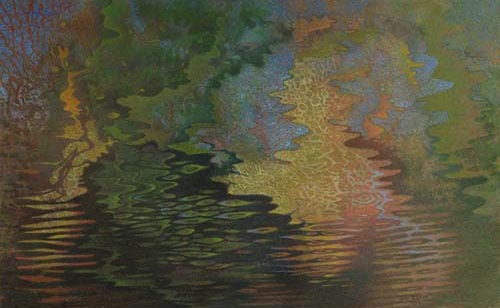

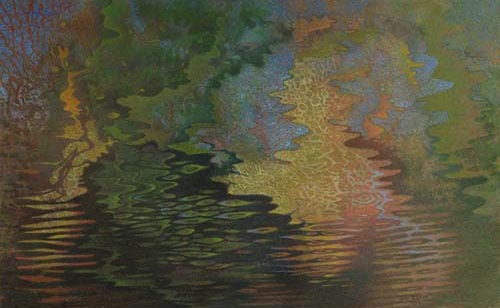

River Mosaic I, John Cullen, mixed media

There’s a fine show of John Cullen’s latest work at Viridian Artists. He paints modestly-scaled abstracts that begin with a kind of AbEx experimentation, where he allows thinned acrylic paint to drip down a sheet of paper. In other words, he lets water have its way, at the start, and then he begins to build on the trail it leaves behind with pencil and more acrylic. That may sound like a pretty dry way of describing an artistic practice, yet Cullen is all about the wet. His paintings evoke the flow of water in all its forms: streams, raindrops on glass, mist and clouds. While so much abstraction builds from geometric exploration, Cullen’s provenance is really physics: the irregular, organic waves evoked by light reflected on fluid. He ends up with mosaics that appear to have the intricate order of fractals. His colors glow and hint at different states of consciousness, not simply different angles on the outer world.

His current work builds from a wavy, warped grid, a skeleton, of vertical and horizontal axes, which provides an anchor for his improvisations with color. If you look long enough at some of them you realize he’s created an abstraction from an actual image of a scene reflected on rippled water. You see bits of blue become sky, and tiers of green resolve into trees that surround it. There’s a mosaic quality to his technique inspired by pointillism. Yet he found that Impressionism didn’t allow him to create the color harmonies he wanted MORE

June 9th, 2013 by dave dorsey

The Great Piece of Turf, Durer, 1503

“The piece of turf must have been dug not long after sunrise, for the florets of the dandelions are tightly closed, and the leaves below them are still moist with the morning coolness. Such a clump of plants and grasses might be found today along any country road, in Europe or America, where it dips down into the dampness of a hollow. Besides the dandelions there are the fleshy leaves of the great plantain, creeping Charlie, and a dwarfed feathery shoot of yarrow. As for the grasses, they are the most commonplace–meadow grass, cock’s foot, the thin spikes of heath rush. “In truth,” Durer wrote, “Art is implicit in nature, and whoever can extract it has it.” –Francis Russell

Wish I’d painted that.

Or written that.

June 6th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Rutabega, Amy Weiskopf, oil on linen, 2013

Size: 6 x 8 inches. Hirschl & Adler.

June 5th, 2013 by dave dorsey

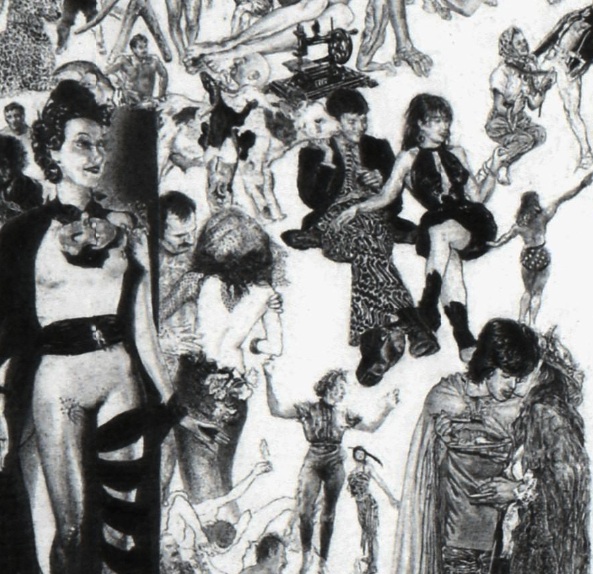

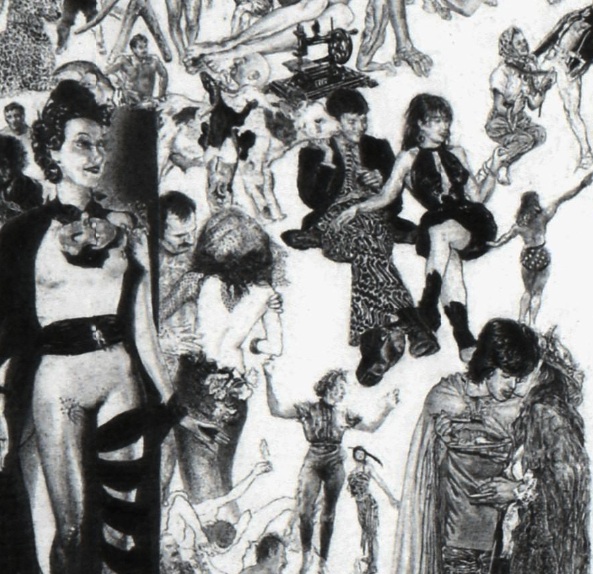

Detail from Libidinal Economics, Rafael Leonardo Black

“So the Dalai Lama says, there won’t be any money, but when you die on your deathbed, you will receive total consciousness. So I got that going for me. Which is nice.”

—Bill Murray, Caddy Shack

On the other hand, sometimes in the end there’s even a little money for all the effort: “Discovered at 64, a Brooklyn artist . . . “

June 4th, 2013 by dave dorsey

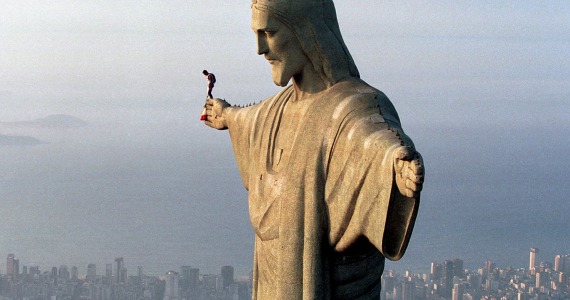

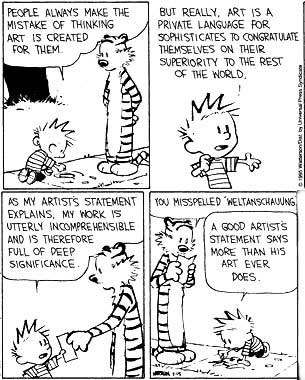

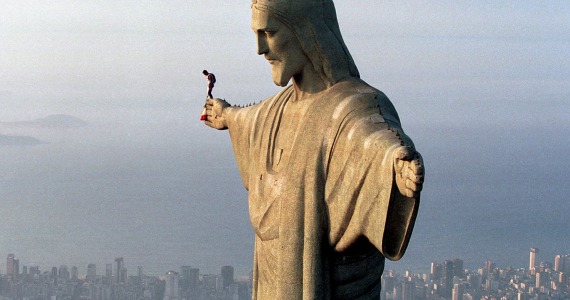

Oh, good grief

And then she Instagrams it. More here. (You have to check out The Scream. Just scroll down a bit for a munchable Munch.)

June 3rd, 2013 by dave dorsey

Eggplant and Bok Choy, oil on linen, 20″ x 36″ at Memorial Art Gallery this summer

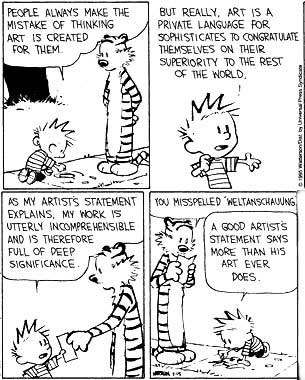

In July and August this year, visitors to our local museum in Rochester, the Memorial Art Gallery, will have the chance to press a few keys on their cell phones and listen to me and quite a few other artists talk about our work. This morning I recorded sixty seconds of commentary on painting and why I do it. I was fortunate this year to have three pieces chosen for MAG’s 64th Rochester-Finger Lakes Exhibition. All exhibitors were requested to record a brief artist’s statement for viewers to hear as part of a recorded tour. So, not only will those in attendance have a chance to see my work, but they can listen to me talk about it as they do. Off-hand, this strikes me as a little too much of David Dorsey for most people’s taste, but maybe it will be sufferable since I kept my recording within the time limit.

Once again, this has been a chance to face the challenge of the dreaded artist’s statement. I’ve approached this from many angles over the past few years, and it’s difficult to condense into a few words something as elusive and complex as the act of painting as well as the totality of what drives a person to paint. It’s like asking someone to say, in half a minute, why life matters. Especially if you have an aversion for sounding grandiose and/or pretentious, and I do have that aversion, despite all evidence to the contraryon this blog. So here’s what I came up

MORE

May 31st, 2013 by dave dorsey

May 23rd, 2013 by dave dorsey

It’s just air in there.

From The Atlantic, how performance art, essentially, helped save lives in World War II. Talk about art mattering.

May 22nd, 2013 by dave dorsey

Untitled, Gregory Crewdson

When it comes to photography, I’m a Gary Winogrand kind of guy. I like it spontaneous, fleeting, and unpremeditated. Like a good haiku. But I love Gregory Crewdson, whose shots are as artificial as a movie full of FX. Go figure. I first encountered him, without knowing anything about him, when I bought the Yo La Tengo album whose cover appears above, more than a decade ago. What looks like a great documentary about him was making the rounds this year and is now available on demand from Netflix.

May 18th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Seniors wearing nature on their heads. Some great shots.

May 17th, 2013 by dave dorsey

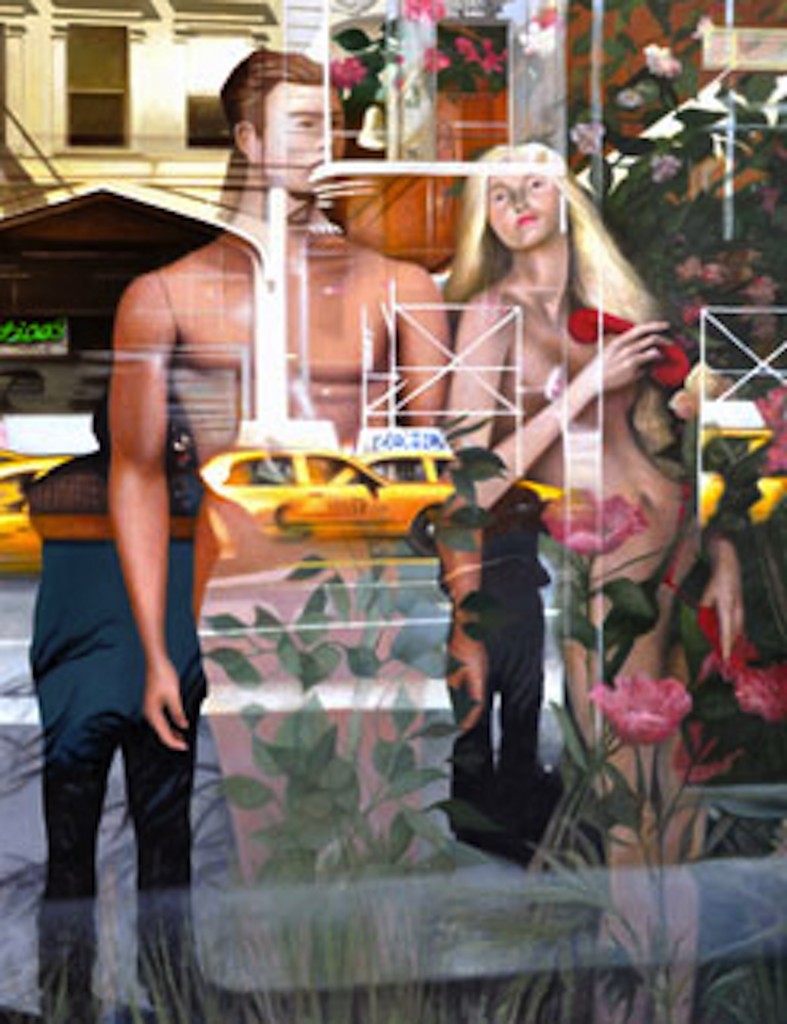

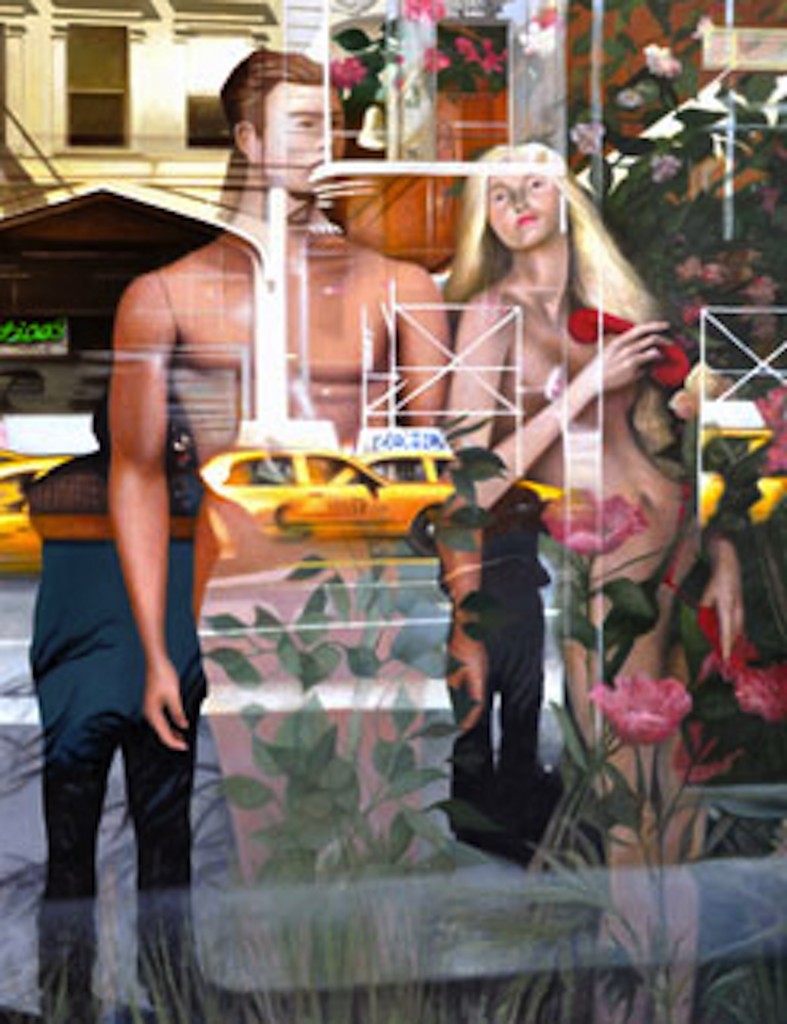

Adam and Eve on West 57th St., Thomas Insalaco

Thomas Insalaco’s new painting, on view at Oxford through June 1, is a beauty. It feels like a step into a new frontier for him, an advance toward something even more intriguing than what he’s done up until now. I’d walked through most of the show before I finally paused in front of this large oil, and I was stunned by it before I even realized who’d painted it. So much of Insalaco’s career draws from his love of Caravaggio, so the ambiguous complexity of this painting’s composition and color threw me off the scent. It’s not a bright image—much of his work looks and feels dark—yet the baroque murk that always lurked behind so many of his foregrounds doesn’t swallow any detail here. Even in the darkest passages, he has spent a great deal of time lovingly rendering significant and beautiful detail.

I have a lot more to say about it, but first some praise for the exhibit as a whole. Jim Hall has assembled an especially strong invitational show, built around Galen’s philosophy of the four humors: sanguine (pleasure-seeking and sociable), choleric (ambitious and leader-like), melancholic (analytical and thoughtful), and phlegmatic (relaxed and quiet). The ancient four elements—earth, air, water, and fire—can be aligned with the humors as well, and some paintings in this show take advantage of that. I liked the theme from the start, and, with the notion of earth/melancholy in mind, I painted Skull Unearthed Circa 1930—which will also be on exhibit in the Rochester-Finger Lakes exhibit at Memorial Art Gallery this year. Not everybody warmed up to the show’s theme as quickly as I did: I encountered some head-scratching about it at first from Brian O’Neill, for example who ended up contributing a fine abstract to the show. It’s clearly a stretch to see the connection between some of these paintings and the four humors, but that’s part of the fun with Jim’s themes: how, and if, you can connect the dots. Matt Klos submitted a tiny, pleasingly muddy painting of jars, which I actually like for its enigmatic brevity, yet to entitle it Air seems a bit like giving it an alias in order to smuggle it through the door. (Glad he did.) Some personal favorites: Evening of the Cold Heart, Fran Noonan; MORE

May 13th, 2013 by dave dorsey

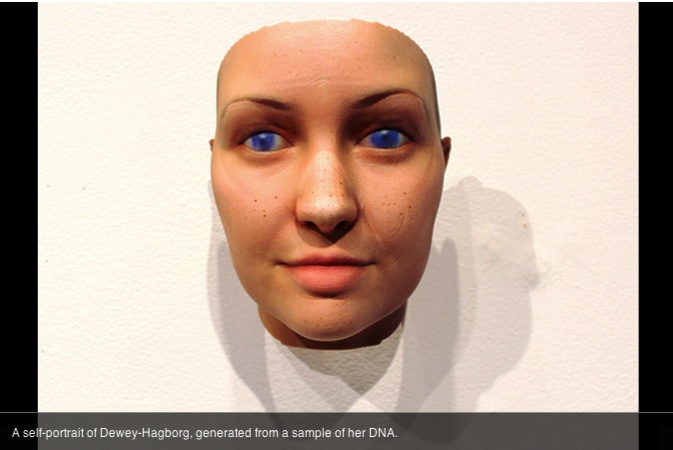

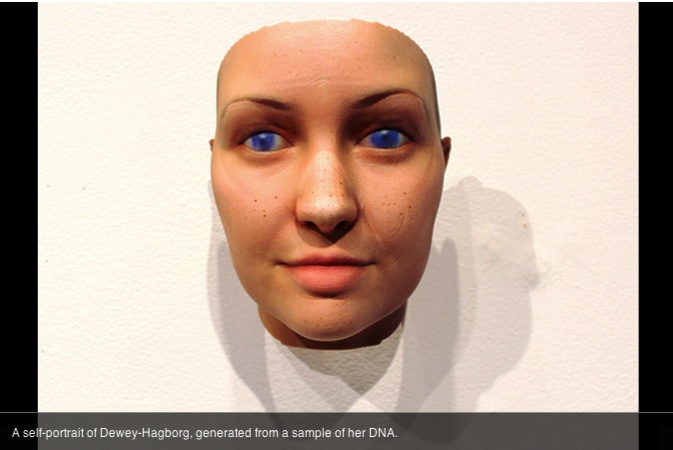

Give her a strand of your hair and she’ll do your portrait.

May 7th, 2013 by dave dorsey

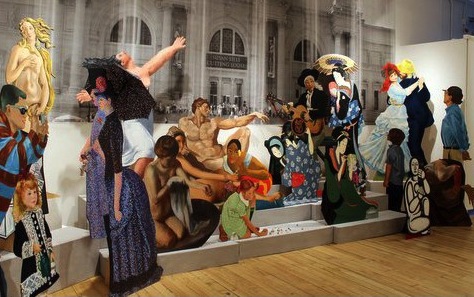

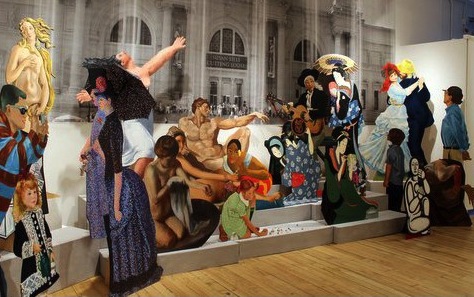

Cutting Loose, Susan Sills, oil on panel

Susan Sills has a delightful solo show of her work from the past two decades at Viridian Artists, perfectly titled Cutting Loose. It’s really two different shows in one, based on her cut-out portraits and figures—life-sized, enlarged pastiches of people lifted from paintings by modernists and Old Masters, painted on birch plywood. The main installation is really a single scene populated with close to twenty of her three-dimensional paintings, arranged as if each of the figures were loitering on the steps of the Metropolitan. An Ingres odalisque reclines in front of a Norman Rockwell girl playing marbles and a bather by Degas. Michelangelo’s Adam reaches for Manet’s guitarist, rather than God. Behind all of them is an enlarged photograph of the Met’s façade, created with wide-format engineering printers, on long three-foot-wide scrolls hung side by side. On the opposite and adjacent walls are shelves displaying the smaller portrait work—Van Gogh, Gauguin, Vermeer and others.

The show does exactly what it’s meant to do: it draws you into the lives of the original sitters while making you feel as if you’re living inside a painting rather than looking at one. It’s all about love and companionship, the love of art history, love of painting, and the love of people in general. Years ago, when I wrote for Buck & Pulleyn, a boutique ad agency in Rochester specializing in marketing for tech companies, on Fridays we often put together something called a “stair party.” It involved pinball. It involved ping-pong. Mostly, though, we hung out on the staircase in our mezzanine/atrium, drinking beer and congratulating one another on getting through another week. The “cutting loose” feel of that cocktail hour is exactly what Sills captures, yet with creatures you would find, normally, in captivity inside the Met, not milling about on the steps out front. The installation embodies for me the sense that painters I love, and even some of their individual works, have been, more than anything else, a source of friendship. Yes, past work and past artists serve as teachers, idols, source of inspiration, models for how to see the world, but mostly remain faithful good friends. My relationship with favorite paintings has all the complexity of feeling and understanding that friendship entails. When I walked into Cutting Loose, my first reaction was, hey, these are my people.

Susan’s been an artist with Viridian since 1979. I spent an hour at the gallery MORE

May 6th, 2013 by dave dorsey

A great reflection on how an artist statement can actually help, without sounding pretentious, obscure or condescending from Hyperallergic:

“I challenge artists to stop looking outside for language and to start digging on the inside for why they do what they do. No one else knows what gets you up in the morning and makes you finish a painting on the way to your day job, or what problems you’re trying to solve in the world by depicting characters a certain way, or why you found that imagery compelling.”