New Year’s Resolution #4

Start. A. New. Painting.

the painting life

Finish painting this little meaningless cupcake. It’s been sitting like this for half a year, already signed (I sign paintings just as I start them not when they’re done, so the signature will fuse into the paint. And then I paint in thin coats on top of it. I’ve been trying and abandoning a lot of cupcakes, partly because, believe it or not, they inspire animosity. A good friend who takes herself very seriously said to me a few weeks ago, with regard to my cupcake paintings, “How can you sleep at night when you send junk like that out into the world?” (Those of you who know her will know exactly who I mean.) With that comment under my belt, I’m so dying to paint a fucking cupcake now. This one’s about a foot tall. I might even do one four feet tall and send that out into the world . . . maybe to one particular address . . .

This might help: scrape the rest of the three-week-old paint off my glass palette. Also, long-term, learn how to play “Blackbird” on that Fender Telecaster sitting on the floor in the upper right-hand corner of the shot (45-year-old guitar, BTW, but all I’ve got anymore is a practice amp my son used for the brief period when he gave guitar lessons a try and then stuck to baseball). Or buy a good acoustic and see if I actually remember how to make a chord. It’s been a while.

“I must go on. I can’t go on. I’ll go on.” That kind of commitment is my native element at this time of year. I’ve got half a dozen things that need doing every day, none of which have anything to do with painting or writing this blog. I’m hoping the half dozen will become merely three and I can get back to painting and writing about it.

A brief piece of writing like this feels like a blessing. You could unpack an eccentric little Nicholson Baker-sized diatribe about art by extrapolating on the insights from this little column in the New York Times. At the very least, I’m going to work on a long post this weekend, based my reactions to it. Here’s a sample:

It is a mistake to credit to an artwork meanings that primarily arise from our interpretative efforts. There is a fundamental difference between discovering meaning in an object and imposing meaning on it. A great work of art embeds categories of understanding and appreciation that we uncover in experiencing the work. It is quite another thing to use an object as a framework for displaying categories that we bring to it. The difference is between discovering a mine that contains gold and constructing glittering objects from dross. — Gary Gutting

What amazes me is how it’s nearly impossible to tell whether one of Rick Harrington’s barns is six inches or six feet wide, when you’re looking at a reproduction. The quality of the small work is indistinguishable form the large. Great, affordable work, and there are still a few that haven’t been bought . . .

“Freud said the goals of the artist are fame, money, and beautiful lovers. Based on my artist acquaintances, I would say this holds true today. What have changed, however, are the goals of the art itself. Do any exist?

“How did the art world become such a vapid hell-hole of investment-crazed pretentiousness? How did it become, as Camille Paglia has recently described it, a place where ‘too many artists have lost touch with the general audience and have retreated to an airless echo chamber’?”

Why the art world is so loathesome. Eight theories from Slate: MORE

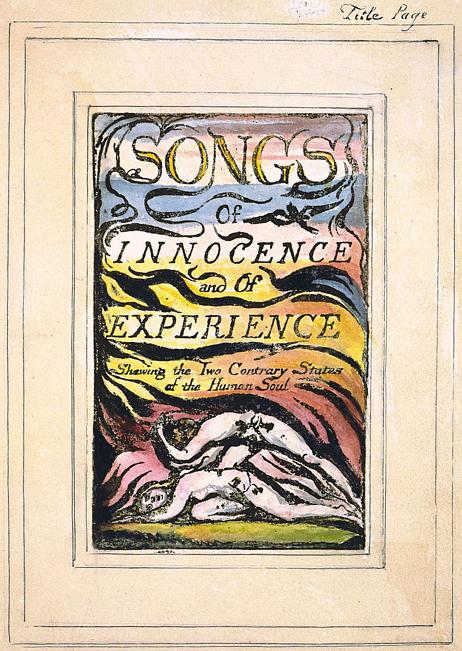

“In anticipation of the birthday tomorrow of the beloved William Blake – the greatest poet of London – it is my delight to publish his Songs of Innocence of 1789 today. When Blake was developing his copper plate printing technique that would enable him to become his own publisher and be free of the restrictions of others, he wrote, “I must Create a System, or be enslav’d by another Man’s.” So I think we may assume that if Blake were writing now he would embrace the opportunity of publishing his work freely upon the internet.” —Spitalfields Life

“In anticipation of the birthday tomorrow of the beloved William Blake – the greatest poet of London – it is my delight to publish his Songs of Innocence of 1789 today. When Blake was developing his copper plate printing technique that would enable him to become his own publisher and be free of the restrictions of others, he wrote, “I must Create a System, or be enslav’d by another Man’s.” So I think we may assume that if Blake were writing now he would embrace the opportunity of publishing his work freely upon the internet.” —Spitalfields Life

Little slow to see this, but have to pass it along, from The Guardian. “When I asked students at Yale what they planned to do, they all say move to Brooklyn – not make the greatest art ever.”

Candy! A language I understand. Finally. The basics of this election, explained with M&Ms. Finally, Barry and Mitt have my attention . . . Not to quibble, but could I get this in Reese’s Pieces?

Jim Mott, my friend the itinerant artist, is in the middle of his Great Lakes tour, which takes him through Buffalo, Cleveland, Detroit and a couple stops in Ontario. He stays with hosts who give him room and board in exchange for a painting of their surroundings. It’s probably the most radical way of being an artist I know. It takes money out of the equation entirely and puts him into a role somewhat like a mendicant monk, or the poet Basho, in his walk around Japan. This kind of itinerant art connects him with people in an extremely personal way—he’s invited to infiltrate their lives and reflect their world back to them through his quickly executed paintings. He becomes a humble servant rather than a seer, producing work that’s instantly recognizable and meaningful, rather than an image that requires deciphering and commentary by anyone other than the recipient. In other words, his project turns a lot of things upside down and the result is MORE

“A portrait is a painting with something wrong with the mouth.” –John Singer Sargent

For a two-artist show that opened last night at Oxford Gallery, where I’m exhibiting 26 paintings, along with a lot of tremendous work by Brian O’Neill, I printed two catalogs, one for me and one for him. I wrote a brief introduction for it, in which I tried to distill as clearly and succinctly as I could, why I paint. I’ve done this a number of time over the past five years, when an artist statement has been solicited for one exhibit or another. This time, I felt as if I came closer than I have in the past:

Painting, for me, is a non-conceptual way of apprehending life. It’s a philosophical stance as much as an aesthetic pursuit. In the process of making a representation of something, the world becomes a part of me in a way that rational thinking can’t achieve. Painting requires me to pay dispassionate attention to the way things are without any motive other than to be aware of them and share that awareness through paint. For me, that kind of mindfulness is entirely different from knowledge and intelligence. Painting isn’t about thinking or knowing. It’s about seeing what’s there; nothing more, but when it works you see more than what’s there as well. A good painting offers the viewer, subconsciously, an holistic glimpse of the world, not conscious information about some small part of it. A painting can function the way the taste of the pastry dipped in tea functioned for the narrator of Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past. In other words, it can summon an entire world from a simple act of perception. That kind of apprehension can offer pleasure, if the work is good, but that isn’t the purpose. It offers a calm state of impartial awareness—a glimpse into the way things are, in a way not accessible to conscious thought—and that kind of attention isn’t something highly esteemed in this contentious contemporary world. In that sense, a painting is a kind of meditation, for the one who makes it and the one who looks at it.

I drove to Cincinnati last week to attend the book party at Manifest celebrating the two annuals they’ve just published—INPHA 1 and INPA 2. The books are an overview of examples of what Manifest considers best in current contemporary photography and painting. These are beautiful books, packed with incredibly accurate reproductions of work from around the world—for INPA 2, out of 1310 entries from 452 artists, Manifest’s jury chose 118 works by 72 artists. As the organization says of the painting annual on its website:

As a carefully designed book, the INPA enables Manifest to assemble a diverse array of works from around the world, without the limitation of physical availability, gallery space, or shipping logistics. Manifest’s book projects support our inquiry into the creative efforts of artists working today and serve to document the exceptional results for posterity, distributing artists’ efforts outside our gallery’s geographic radius.

I’ve been thumbing through my copies every day since I got home, and I’m still finding surprises and incentives to get back to the easel. It was a slightly absurd distance to drive for a two-hour event, about 825 miles there and back, but I stayed the night at Rush Whitacre’s studio in Beverly to divide the distance, and that turned out to be half the fun. I pressed apple cider with Rush and his friend Butch on Thursday night, until midnight, and then drove to Cincinnati with him the next day. We got together right after the event at Suzie Wong’s for a late dinner with Jennifer and Randy Wenker, and laughed MORE

Last year, I was hanging around Viridian Artists, up to no good, and Simon Cerigo came in to visit, and we talked about a show at Zwirner which I’d just seen a few hours earlier. I was still raving about it. “Too finished,” he said, of Michael Borremans, which at the time I thought was funny, since the technique I’d seen was anything but finished. It was economical, supremely confident. Masterful. (I haven’t checked lately. Is it OK to say master, if you don’t say “old” first?) This painting reminds me of that work, in retrospect. The body is just sketched in. The wiry hair is preternaturally rendered without a lot of arduous specificity. Try doing that sometime, that hair. Maybe it’s just the way the canvas is lit. I wish. And it’s just a study for The Surrender of Breda. Thin under-layers of paint with hardly a second or third application. You mistake the weave of the canvas for the weave of the sleeve, the paint is so insubstantial. I think maybe I’ll try doing nothing but studies. Oh, yeah, this is how it looks after the incredibly successful restoration a few years ago. (Somebody, please forward this to Cecilia Gimenez.) Anyway, Simon, I understood what you meant. Exhibit A, see above. But you’d still probably say, “too finished.”

The New York Times this morning published a great, balanced overview of the farcical tempest that’s been brewing over the tenure of Jeffrey Deitch at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art. A couple months ago, a friend urged me to write about it, but I demurred, expecting someone more informed to do a much better job. Of course, as usual, that someone was the New York Times. As its story lays it out, the financially ailing museum had recruited Deitch to come in and turn things around, which he proceeded to do, by organizing shows and events, working outside the usual curatorial channels, bringing more people and more revenue through the doors, but alienating many supporters with big names. It would appear that Deitch believed getting people into the museum was more important than providing substance over style—for example, by hosting a show about Hollywood curated by Hollywood, meaning a James Dean exhibit curated by artist/actor James Franco, for example. However, he was doing his job. In short order, Deitch increased public awareness of the museum and lured people into the building. Once inside, the public was free to wander around and check out more substantial work. It’s a museum after all. That’s what these places do: offer anyone willing to pay admission a glimpse of ostensibly great art, if you’re willing to find your way to it. (Bread crumbs might work at the Metropolitan, which is always a challenge, though I’ve never tried it.) Long story short, Deitch infuriated a core group of highly-regarded artists and curators who “constitute a crucial faction here,” as the Times put it. Things reached a boiling point with one particular show: MORE

Not too long ago, Kat King thought her artwork was actually coming alive. One of the dragon models that she’d assembled from leaves and husks and flower stems seemed to be moving on its own. When she got closer, she realized small insects had hatched and were emerging from the pods and husks she’d found in wooded tracts not far from her home in Chicago. She fetched a pair of tweezers and pulled the burrowing bug out of her dragon and was astonished to realize this was an exotic insect she’d just happened to read about: the death watch beetle. A little fumigation solved her problem, but the resonant mystery of the event wouldn’t die.

What made this episode so bizarre was that a short while earlier she’d gotten the word paradox stuck in her head and couldn’t get it out. So she looked up its definition, and it led her to a Wikipedia entry on paradoxical or cryptic animals.

As she tells it: “I found centaurs, griffins and serpents, snakes, and then dragons and then, after that, there was something called a death watch beetle. So, not long afterward, I . . . noticed little brown bugs were emerging from my assembled dragon.”

“Let me get this right. You had these insects living in the models,” I said.

“Especially the dragons. The pods must have had these things in MORE

Also from the current Harper’s magazine, a glimpse of an exhibition at Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. In my view, more than almost any painting he did, other than one particular landscape in the phenomenal Whitney retrospective, (Heat Lightning,) this work fulfills Burchfield’s lifelong yearning to be a classic Chinese scroll painter It’s a bug he picked up while working as a guard at an Ohio museum. Every time I go back to his work, it looks more vital and original and somehow accurate. It shows you what’s actually there, not just what’s there to be seen. Those intense green marks of refracted sunlight at the top of the tree, echoing the little green notes at the bottom: you can almost hear this painting and feel the Indian Summer heat. I always imagine Burchfield, toward the end of his career, saying, “Oh, to have lived a thousand years ago in China.” I say, “Oh to be Charles Burchfield.”