The timeless secret of creativity.

“Being stuck in one place and bored out of your mind is the key to creativity.”

–Aimee Mann to Marc Maron

the painting life

“Being stuck in one place and bored out of your mind is the key to creativity.”

–Aimee Mann to Marc Maron

Big up to the paintings and the post at Hyperallergic. It’s on my list for a gallery/museum tour in a week or so. “Poons carries the torch, heralds the song, then asks us to abandon all knowledge as we stand in rapture. Empty.” Abandon all knowledge, ye who enter here. Yes indeed, as an approach to painting in general, not just Poons.

My friend Rick Harrington,just went through cancer surgery. They caught all of it, as they say, but the recovery laid him up for a couple months. Two months without painting and the mind begins to circle around how Quixotic the whole enterprise can feel. But he’s ready to gear up again and was in good spirits when I finally drove out to see his studio in East Avon, south of Rochester. He rents a house and studio next to a large expanse of farmland, which looked ready for a crop already, plowed and dark with snowmelt beyond the converted garage where he paints. (The temperature is back to 15 degrees today, so that melt meant nothing.) We had tea in his house and talked for nearly an hour and then spent another hour in his big studio, talking about painting. One thing we agreed on: this economy isn’t good for anyone, least of all artists. He had a couple years where he was selling work so fast, he could hardly keep up with the demand, and then came the real estate crash, the recession and this so-called recovery, which is mostly about Wall Street. His paintings still sell, but he doesn’t think he can map a path toward economic self-sufficiency as easily as he could have only a few years ago. The dream of forgetting about money and thinking only about how to do better creative work: how many artists can live that way? A lot fewer than were doing it before 2008.

Rick has a dog, Ulysses, who is closer to a Shetland pony than anything actually canine. He’s also more mastiff than Rottweiler (a cross between both) who was always at our sides, looking for affection, hugs, and stray crumbs of the chocolate chip cookies Rick had just baked for his two sisters who were also recovering from health issues. We talked about money, MORE

My Bloody Valentine, after two decades, finally released another album. I’m thinking, what’s the rush? I still haven’t exhausted Loveless, from 1991. There’s no point in repeating the legends about this album and how it was recorded over two years. It seems tailor-made for elitist hipsters, since it makes every effort to take the edge off the music’s beauty. It has to be one of the most manicured recordings in history engineered to sound as close as you can get to the effect you get when you’re hearing three radio stations at once near some Bermuda Triangle of the dial. For me, this is Ireland’s lyrical, melodious answer to Sonic Youth’s raw power, but more ethereal and yearning and, well, innocently hopeful. The trick is to zero in on the harmonies and melodies behind the disguise of distortion. It seems you’re hearing most of it, muffled and remote, from six or seven floors above your garden apartment. So you end up playing these tracks over and over, trying to clearly discern these songs you’ll never being able to quite pin down because . . . well, let’s try again . . . because they’re being played about a mile away, and they’ve been carried to you by the shifting wind. If only you could be right there where it’s happening, hearing it the way it really is! From only a quarter mile away, say. And that’s what keeps you coming back.

Like so much of life, it’s almost there, right in front of you . . . and yet . . . and yet . . . . Turn Loveless way down, lower than you play anything else in your collection. It still sounds incredibly loud, just farther away, at a lower volume. Listen with earbuds and the difference is even more distinct. What’s noise equalizes with the actual music and you still can’t understand a single word of the lyrics but the fuzz begins to sound like the innate sound of an electric guitar and the track relaxes and everything falls into place and an actual song, arranged with haunting complexity, floats up out of the auditory bed of white noise. And yet . . . the perfect experience of hearing it is still just slightly out of reach . . .

Is anyone as weary of the term “cutting edge” as I’ve always been? It is possible it will ever be retired? At N+1, you’ll find an essay built around the plight of Steven Cohen, a major art collector and the head of SAC Capital, currently under investigation for insider trading. The author of the piece Gary Sernovitz, draws loose comparisons between the “edge” that traders seek, which can drift into the illegal exchange of non-public information, and the “edge” that artists attempt to ride in their work. It’s more of a poetic play on words than anything else—both edges put you ahead of everyone else, by a little or a lot, but one is illegal and the other simply represents an exhausted idea of what matters in art. Both do represent something that can result in a lucrative advantage over competitors. The essay has a sort of proclamatory, elegiac tone that feels more enthralled by the notion of this elusive “edge” than the essay’s skeptical take on Cohen would seem to warrant. Some fine points are made though, especially these on the notion of edgy “newness”:

A visual artist hits his audience with a visceral punch. The potential responses to a work’s “newness” seems much more binary (than a response to the influence of previous writers in, say, fictional prose). One would continue reading prose that is Bellowish and happily let the author have her influences. One would wonder after seeing a Pollockish drip painting whether the painter was an ironist or a hack.

(Some of use wouldn’t wonder this at all, but a lot would.)

How hard it must be now for an artist when it seems that not only has every material form and format imaginable been tried to express Truth and Beauty but every idea has now also found material form. I watch in awe as artists rise to face that challenge, and even more so when they succeed. But sometimes I feel like I’m witnessing the strain. All artists respond to their inner life and the outer world and other art in some mix. These basic ingredients have not changed. But too often, after leaving a contemporary art exhibition, having hungrily wanted a powerful aesthetic experience, I wonder why I was left cold. . . it feels, sometimes, as if an edge has become the only ante to be exhibited at all. As if the edge has become the whole point.

(I’m not disagreeing, but the edge became the whole point a long time ago.)

Artists—traders—the Art Collector himself—are faced with the efficient market, the weight of precedent, all that has been and is being done. Every day it gets worse. But the best of them, like de Kooning, are mercury, racing to be first to an edge before it disappears.

This is now the template for the career of a successful artist: a few incandescent years, a few decades, and then repetition, self-parody, irrelevance, death. But that’s what we admire about them. Their fight against their condition is our fight against our condition. They are trying to fix a vanishing edge in a material form. And that struggle against the mortality of the edge, which is the mortality of every minute, which is mortality, is affirming and heroic and generous.

Just shoot me now. If “newness” is the game, then all of what Sernovitz says is totally on the money, as it were. If “newness” has ceased to be the point, and it has, then none of what he says really applies to the making of art. A compelling quality of freshness—not some critically-identifiable “newness” that can be extracted from a particular work—finds its way into the picture when the artist remains faithful to whatever compels him or her, individually, to get to work in the first place. That impulse, as with De Kooning, whom he was continuing to celebrate there in that last quote, used to come from an historical struggle with predecessors, a wrestling match with the anxiety of influence, as Harold Bloom called it, in another context. But the “new” is new now only in the sense that a particular snowflake or an individual person is “new”. Considered from one perspective, a work of art is just the same old thing, identical with all the rest. But get close enough, emotionally, personally, or just optically, and some work is utterly unique because it’s so utterly the person who made it. The quality and power of that quiddity—yeah, that’s right, I used the word quiddity—depends on qualities of the individual artist’s personality and character, not on where the work fits into any sense of historical “newness.” On the subject of not needing to be at the edge, one more quote from the interview with Ran Ortner I pilfered in my previous quote, about Rembrandt’s last years:

Rembrandt starts his career in Amsterdam . . . where there is lots of new wealth. He becomes extremely successful and buys an expensive home and fills it with antiques: Roman armor, fossils, collectibles. He marries a woman he adores, and they have four children. He has everything. And then three of his four children pass away. His wife dies. His work is no longer fashionable. Amsterdam moves into the second generation of wealth, and the nouveau riche prefer the rococo, the intricate and overdone. Rather than follow trends, Rembrandt becomes more and more direct and brutal, his style rougher, the work more immediate. His paintings don’t sell. He loses everything. But it doesn’t discourage his inner need to be fully who he is . . . when he paints his self-portrait in golden robes, he’s lost his home, is bankrupt, and is living in a poor part of town. Yet he paints himself as a king on a throne because he has his empire of dirt.

His little nod to a Nine Inch Nails lyric baffles me, since it was a song about moral desolation and addiction, not noble poverty, but you get his drift. No cutting edge to be found anywhere in this. No whiff of anything “new” anywhere in that scenario. The new was probably off doing something far less interesting at the time. Whatever’s merely new eventually gets old, and Rembrandt’s work never gets old.

What the word artist implies is looking for something all the time, without ever quite finding it in full. It is the very opposite of saying “I know all about it. I’ve already found it. As far as I’m concerned, the word means, “I’m looking. I’m hunting. I’m fully involved.”

–Vincent Van Gogh to Theo, from an interview with Ran Ortner, who paints the ocean.

From the interview:

It wasn’t until I read Thomas Merton that I came upon something that helped me. He said there’s nothing as old and as tiresome as human novelty. There’s nothing as immediate and new as that which is most ancient, which is always in the process of becoming. Wow, I thought, that is exactly how I experience the ocean.

Something happens to time when you’re painting. You’re able to bring the span of your entire life into this one moment and into these few materials.

That’s what makes art great. It’s a physical object that carries some of the magic back from the mysterious place. Something I have brought back with me from the descent, a token of the experience.

A scientist, a monk, and an artist are all looking for the same thing, some deeper reality outside of themselves, or inside themselves.

The rules of the contemporary art world are crystal clear . . . .if one works with representation one must use irony, social commentary or wit in the work to avoid becoming saccarine or decorative.

Sorry, but gonna have to break those rules . . . as Ortner himself does.

Rick Harrington emailed me this interview. Love it.

Rick Harrington emailed me this interview. Love it.

“Build up your self esteem to the level that might seem unwarranted. This will help you ignore both positive and negative responses to your paintings. Both are usually misguided, since they come from the outside. Be your most severe and devastating critic, while never doubting that you are the best thing since sliced bread.”

“The moment something works well and is under control – is the time to give it up and try something else.”

“Put all your eggs in one basket. Precarious situations produce intense results.”

“Forget subjective, it is mostly trivial. Go for the universal.”

“Schiller decided that there are really just two kinds of artists: naive and sentimental. Naive artist works with the first-hand experiences, uncompromised by self-analysis. Sentimental are works that are self-aware of their place in history, theory, etc. One usually sees this kind of work accompanied by an artist statement. I think I am more naive than sentimental in the things that inspire me.”

–Alex Kanevsky, Vivianite

I wasn’t able to attend the reception, but this show got a huge turnout. Can’t wait to see the other work in this catalog. A little shout out to the participants from Jason Franz on his Facebook page:

This one is a beauty! Including works by Shelby Shadwell,Joseph Crone, Aidan Jos Schapera, Elise Schweitzer,Shannon Hartman Cannings, Gaela Erwin, Rob Anderson, Bain Butcher, David Dorsey, Brett Eberhardt, Bridget Grady, Nathan Haenlein, Mark Hanavan, Phillip Jackson, Bo Kim, Kent Krugh, Anne Lindberg, Louis Marinaro, Laurin McCracken, Michael Meadors, Joseph Moniz, Douglas Norman, Ann Kaplan, Jose Sanchez (Felox), Benjamin Shamback, and Dennis Wojtkiewicz.

I know what this one looks like already:

“Given that the Venice Biennale has metastasized in recent years into an all-out plutocratic orgy featuring Louboutin-shod scenesters pushing and shoving to get onto Roman Abramovich’s yacht, “J.M. Coetzee, curator” sounds at first like a joke from some art world Onion—as unbelievable as Thomas Pynchon appearing on “Oprah” or Joan Didion doing a Reddit AMA. Coetzee may or may not be the greatest living writer in the English language, but he’s certainly the gravest. And while sending Coetzee to Venice may result in a fish-out-of-water surprise hit, I wouldn’t bet on it. He’s a writer whose whole career has been devoted to the virtues of seriousness, but in the funhouse of contemporary art, seriousness doesn’t look like a moral imperative. It looks like a stylistic tic, and I wonder if he realizes that.”

The New Republic, Feb. 7, 2013

A few days ago, I read another great piece from Roberta Smith. It’s ostensibly about how museums need to give far more prominence to folk art and outsider art. Yet it’s really about the need to break out of many of the preconceptions that have ruled art for so long. In it, she hit many of her refrains about how the art world needs to shrug off conventional guidelines for determining what’s “important” in art. She’s said it before, she’ll say it again. She suggests, sensibly, that it might stir new insights to give folk art far more prominence, juxtaposed with mainstream art from the same period. Her larger point, though is that it would also make sense to abandon the exhausted vision of art as marching forward through various periods toward something better, or more relevant, or more . . . X . . . pick the adjective of your choice. May I suggest scrapping the word “important,” since the best literature, movies, art and music aren’t about anything but the totality of life, which isn’t great or trivial, or important or unimportant–it just is. Being intensely aware of the odd fact of just being, and only that, seems to me the highest aim of art, even though it often seems to amount to nothing. The hard part is simply being fully aware of what’s there, the isness of whatever it is you behold. This used to be the imperative of art, to simply pay passionate attention to whatever it is that’s before you, even if it’s nothing more than the work itself, back before art lowered its aim so dramatically over the past fifty years. (Spare me the exceptions to this, I know there are a ton of them.) Smith has been a skeptic about a lot of fundamental assumptions through the years: that artists need to have an art school degree, that we should refer to making art as a “practice,” as if it were a profession like medicine or jurisprudence, and that the people who determine what’s great and what isn’t always know what they’re doing. Anyway, it’s a great piece, which extracts more significance than I ever expected from a subject that sounds at first as if it ought to be dusted off for a dry discussion on how to curate one’s permanent collection . . .

What surprised and pleased me, though, is that she brought to mind one of my favorite artists, Nick Blosser, a painter in Tennessee whose work I saw many years ago at a little solo exhibition at the Adam Baumgold Gallery on the Upper East Side, after spotting a notice in The New Yorker. Blosser strikes me as someone who works in a style close to folk art, and he doesn’t seem to fit anywhere into that old historical agenda that sees 20th century art as a march from one outmoded movement to the next, toward greater and greater . . . what . . . freedom? . . . (insert whatever adjective you picked to fill in the blank above.) He simply works in an extremely personal way, building very small pictures in a style that at first seems primitive and then achieves a kind of haunting, dreamlike music, full of the seasons, in love with the woods, and seemingly ecstatic about almost anything he happens to see. He seems to have paid no mind to the course of modern and postmodern art. He may look like one, but he’s no outsider. He’s won two National Endowment for the Arts fellowships and a Rome Prize fellowship. Yet he’s done it all without trying to fit into the cool, cerebral, ironic sophistication that has ruled visual art for so many of the years he’s been working. The vitality of what he does, for me, stands as a confirmation of what Smith says in her piece: the freshest and best can come from the most unexpected places and from people who could say, as Oscar said to Lucinda, “I don’t fit.” Now there was an artist I admire, that Oscar. He was so much of an outsider, he didn’t even exist.

What you would see in the sky if city lights didn’t obscure the stars. Great slide show in the Times.

I stopped into Viridian Artists last week to pick up a painting I’d shown in Endings and Beginnings, because I needed to ship it to Manifest for their current exhibit. With the parking maneuvers of an unlicensed limo driver, risking big parking tickets at rush hour, I got the job done, I’m proud to report. I’m getting as bold and improvisational as a seasoned New York driver, though I’m only an interloper in this town. I parked illegally at Second Avenue and 51st St., in the bus lane, and on a crosswalk. (You would think I was kind of a big deal.) I sprinted into UPS, plopped my big, pre-labeled pre-paid shipment onto the counter, and rushed back out to the car before anyone would have time to ticket or tow me. Gotta love those emergency blinkers. Before all of these urban scofflaw antics, I had time to catch up with Vernita N’Cognita and Lauren Purje, who were both on duty at the gallery desk. I lingered quite a while taking some iPhone shots of the current Viridian affiliate show, Disconnected Realities, getting in everybody’s way and in general feeling like an uninvited guest. It gave me time to warm up to the way the whole show looked. It seemed to hang together more coherently than most of the group shows we’ve had at the gallery over the past year, including ones I’ve been in. There was a lot of work on the walls, but it was hung in tight clusters of individual style that gave me a pretty clear sense of each artist’s strengths. It helped that most of the work was fairly small. A few quick impressions:

What I noticed about the photographs by William Atkins was how they captured contemporary sitters with techniques that give the MORE

. . . who died a few days ago.

Musee Des Beaux Arts

About suffering they were never wrong,

The old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position: how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along;

How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting

For the miraculous birth, there always must be

Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating

On a pond at the edge of the wood:

They never forgot

That even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course

Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot

Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer’s horse

Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

In Breughel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

–W.H. Auden

“The enemy of art is the absence of limitations.” – Orson Welles.

Taking a lesson from J.D. Salinger and Thomas Pynchon, Dave Hickeys says he’s retiring from his role as gadfly to the art world. He’s disgusted with the whole game, and he isn’t going to take it anymore. He’s going to quit writing about art. I’ll believe it when I see it. A museum director I’ve known for many years sent me one of the best recent pieces about him–the more you hide, the more they seek, if you’re famous. My friend sent me a link because he knows I’ve nourished myself on Hickey’s ideas since I discovered the man’s writing, belatedly, only about five years ago. (Two years ago, in Albuquerque, I walked up to Hickey himself and with dorky humility requested and got his autograph on the title page of my copy of The Invisible Dragon. Hickey was there to speak with Ed Ruscha at a symposium on fine art printing. He was kind and friendly and gracious but did not invite me to have a drink. Shocking! Ed Ruscha, sitting at the same table, bided his time and didn’t make eye contact even though I was attending with a friend of his.) The article I’ve just finished reading is by Laurie Fendrich, a professor of fine arts at Hofstra University. It’s a fine introduction to the man and his views. She lists his credentials, such as the MacArthur genius grant, his history as an art dealer, his editorship at Art in America, and his wild man bona fides, which unavoidably sounds like vicarious name checking when anyone gets down to listing his coolest acquaintances—Hunter S. Thompson and Lester Bangs, for example. (OK, now I realize I shook the hand of a man who was friends with Lester Bangs . . . ) But what she nails is Hickey’s central notion that “beauty” is the language of art. Ironically, French structuralism is his critical method of choice, yet he claims to practice a subtle kind of deconstruction distinct from the political cudgel postmodernism has become in American academia.

All in all, Hickey seems to be pretty busy writing for somebody who’s giving it up: coming out soon will be Hot Chicks (would it be named anything else?) on female artists, and Pagan America, to elaborate on his view that American life is, MORE

Mangroves from my parents’s back door at dawn

First of all, there’s one central irony in all this. I hate crickets. When August arrives, they emerge and begin that creaky, rhythmic din that at first seems seasonal in a nice way and then quickly begins to sound like a monotonous dirge announcing the heat death of summer. Soon, they begin to ride into our house on cut flowers and then crawl into our cabinets and start chirping in a way that’s nearly impossible to locate. Somehow they’re able to send out waves of throbbing sound for hours at a time and it seems to come out of all the walls at once. If I do find them—they’re tiny—I’m unsparing. They either die or are caught and tossed outside. So that’s my official position, for most of the year, on crickets. You may be amused by this as you read on.

That said, I spent most of last week on Longboat Key, a barrier island off the coast of Sarasota, helping my parents settle into their home there for the next four months. My studio stayed in Pittsford, NY, of course, so I’ve been unable to paint for almost a month actually, with my income-generating work as a writer taking up most of my time, which will continue for another week or so. I flew to Florida with them and stayed for five days and passed most of the first three days doing nothing but handling random simmering emergencies: restoring cable service, which took nearly 24 hours off and on; two separate plumbing repair jobs; grocery shopping at the new Publix (it looks like three Whole Foods fused into one shiny new uber-market); turning on the water heater which had inexplicably been turned off; resetting passwords; rebooting anything rebootable; and a dozen other tasks that neither of my parents is young/healthy/Internet-friendly enough to do. MORE

There’s a great article about photographer Garry Winogrand in the most recent Harper’s. (You have to subscribe to view it online.) It describes how, when he worked up a little steam, he would shoot his work continuously, exposing roll after roll of 400ASA film, sometimes taking shots as he drove around the city, obsessive, compulsive, in thrall to the shutter button. The speed of the film enabled him to do much of what he did, which feels to me like something a Beat generation writer would have done, as well as a body of work Walt Whitman could have fallen in love with. The endless series of shots, often left in undeveloped rolls, reminds me of Kerouac with his continuous scroll of paper running through the typewriter, typing furiously and never looking back. His methods, shooting as a knee-jerk response to nearly everything he looked at, has an indiscriminate Zen-like spontaneity, a ceaseless flow of shooting as a fertile shadow of seeing itself. Almost as if Winogrand was simply trying to leave behind a lesson in mindfulness. As if he wanted to achieve that pinnacle of attention that Eliot attributed to James: the ideal of having a mind on which nothing was lost. His voracious impulse to record the world also reminds me of the polymorphous appetite familiar in Whitman and Ginsburg both for celebrating just about everything that is. OK, so I guess I’ve gone and turned him into a writer. He was just the opposite. There’s always a subject, but rarely a story, in his work. As always, go see for yourself on Google image.

Here are some quotes from Garry Winogrand. Replace “photograph” with “painting” and these comments have just as much significance, more often than not. These are wonderfully written, but his pictures don’t need words. They’re all about the visual and totally “against interpretation.” Sontag would have loved the guy:

Just sent this off to Jason Franz and crew in Cincinnati. I know it’s a little suspect to praise a gallery for showing high-quality work when you’re own stuff is in the mix. But they’re doing more than just picking good work, and they do it in their own unique way. As I’ve said before, I wish they’d clone themselves as Manifest franchises in a lot of other cities. Even if I keep saying that, I’m sure it won’t happen.

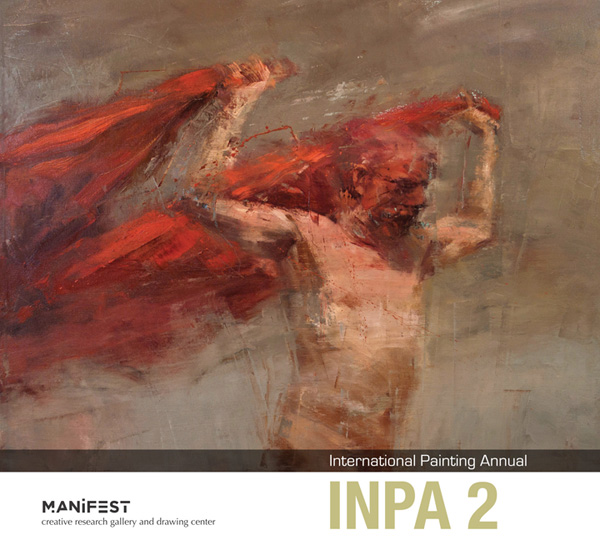

I loved INPA 2, both as a writer and a painter. You included samples of both my writing and my painting, so this edition of the book serves as a validating way for me to introduce people what I’m doing in both areas. Your publications work the way your exhibitions do. They give artists an opportunity to have their work shown alongside some of the best art being made nationally and internationally–without any reference to whether or not it sells or hews to any particular trend or critical school. The fact that the work you select for everything you do is usually less than ten percent of what’s submitted for possible inclusion–and also that your selections are based on the review of a committee rather than one or two jurors–authenticates the Manifest “brand” in a way that’s hard to find in other juried shows open to nearly anyone who makes art. I’m always pleased when I’m able to participate in anything Manifest puts together because its an honor to be selected from among a pool of such worthy art. Your shows and publications strike me as a rare way for people to find work that’s excellent but possibly overlooked by the usual gatekeepers: academia, museums, commercial galleries, commercial art publications, and the mainstream market in general. I also have the sense that Manifest cares about championing art that can communicate with the art world’s equivalent of what has been called, or at least used to be called, in the world of publishing, the “common reader.” The shows are always sophisticated, but they also seem to be driven by an ideal of reaching as large a public as possible–the common viewer if you will–rather than an elite group of initiates (insofar as it’s possible to do that with the way visual art has evolved in the past hundred years).