Archive Page 7

July 1st, 2021 by dave dorsey

Texas Louise, Frank Bowling, acrylic on canvas, detail

You can get a powerful overview of Frank Bowling’s work at Hauser and Wirth on 22nd St. in Chelsea. His efforts in moving paint around can be epic, but he also imported into his abstract expressionist technique images from the world map. A triptych visible as you walk into the gallery shows three images, not of Africa, but of South America, repetitive as a Warhol portrait, but in subtle and rich earth tones, striking and simple. The show runs to the end of July. From the gallery’s website:

The exhibition charts Bowling’s life and work between the UK and the United States. Born in Guyana (then British Guiana) in 1934, Bowling arrived in London in 1953, graduating from the Royal College of Art in 1962. He later divided his time between the art scenes in London and New York, maintaining studios in both cities. London is the city where Bowling trained as a painter and achieved early acclaim. New York is the city that drew him to itself at the height of the Civil Rights movement, where he became involved in discussions of Black Art – New York was a place of fresh energy and ideas for an artist in search of new ways to make paintings.

June 28th, 2021 by dave dorsey

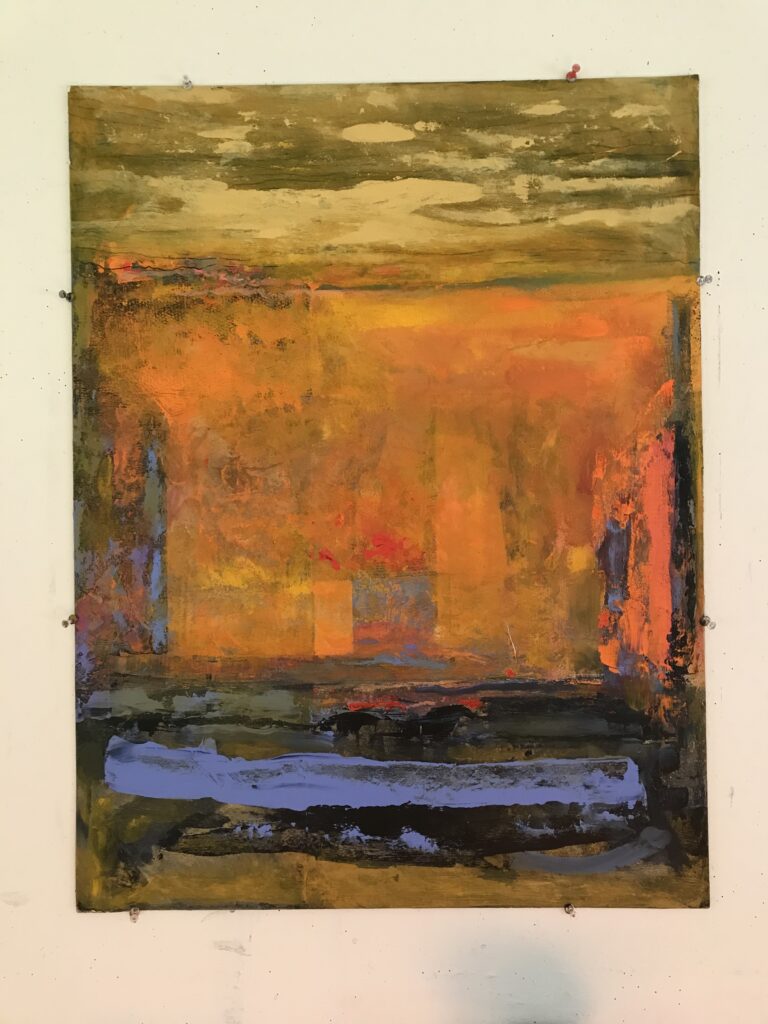

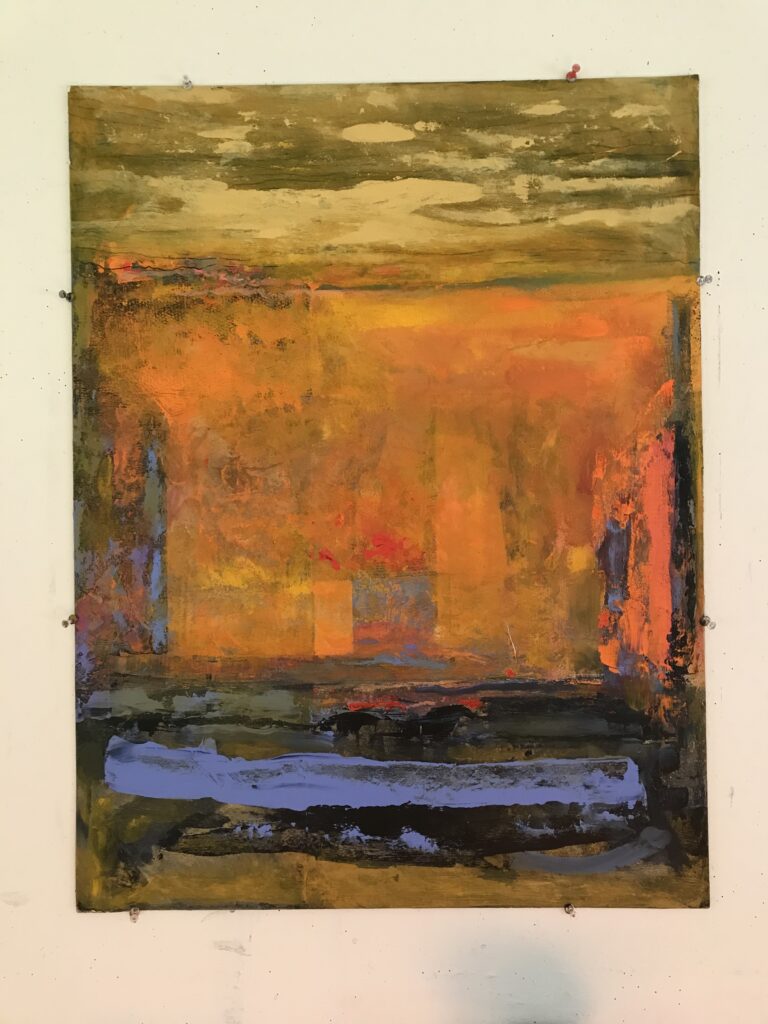

Bill Santelli, Appearance of White, acrylic on canvas at his home

I saw this painting, Appearance of White, completed years ago, at Bill Santelli’s home on my recent visit for coffee with him and Bill Stephens. I was stunned by the mastery of his paint handling here, the restraint of the color, and the rigorous simplicity of the composition. It looks like a visualization of both an internal state of illumination but also simply an evening sky, with the abstract and representational elements so resolutely distinguished from each other, Santelli forces them to wrestle for dominance, the black geometry jutting up from below and also sweeping down across what seems to be a beautifully, naturally executed image of a cirrus-swept evening sky. The long black rectangle, like a squeegee, seems to swipe across the sky from the upper corner, turning that muted purple atmosphere to rusty orange, as if the sun has broken through just at the horizon to immediately tint everything with one last memory of warmth. The angular black voids reach a minor truce with this abstract sky in the bottom right corner, where the sky bleeds into the black and offers a gradual, lovely but precipitous fade into night. The little strip of white, along the edge of that squeegee blade, hints at a greater illumination, and I imagine it takes pride in the fact that the title’s more interested in it than anything else in the painting.

June 25th, 2021 by dave dorsey

Gerard Richter, the Cage paintings.

In the May issue of AEQAI, Ekin Erkan makes an interesting argument against the role of chance in Gerhard Richter’s paintings. He’s responding to an exhibit of Richter’s Cage paintings, a series of abstracts produced according to John Cage’s guidelines for composing music randomly. This sounds like a dry and cerebral exercise, but the paintings themselves are anything but. They’re gorgeous, in large part because, like Rothko, they reach back and employ some of the basic structures of landscape painting and conceal/utilize them in these square fields of smeared, squeegee’d paint. What’s most powerful about this particular series is Richter’s lyrical restraint in the use of color. Deep, rich, and subtle blues and greens peer at you through the gray fabric, the haze, that dominates a canvas. You feel as if you are trying to find your way through a wilderness in the fog, where you get disorienting, tantalizing glimpses of the forest’s beauty, while thoroughly lost. In other words, Richter’s abstraction here seems much more rooted in the the brain’s prehistoric training to look for sky, horizon, land and water, the brain’s predisposition to spot both predator and prey. It isn’t hard to imagine a horizon line across the center of these canvases and see woods, sky, reflections in a lake, evoked by the smears of Richter’s intentionally limited palette.

Erkan seems intent on debunking the role of chance, the “aleatory” element in the production of these, or any paintings, because what evolves in the process of making them has been structured and determined in large part by the rules, conscious and unconscious, the artist observes in the use of paint. This is accurate, and applies even to Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings, which have to be the most random canvases ever produced. But any painter knows how, in its most crucial ways, a particular painting is utterly unrepeatable. The exact proportions of paint in any mixed color will always be subject to the accidents of mixing them in the heat of a session at the easel: there is no way to precisely duplicate anything that happens in the execution at any point in the making of a painting. The Pointillists may have tried. Conceptual artists who simply write out the instructions for the production of a particular work, like Saul LeWitt, might be said to have eliminated chance from the game. Or someone who devised elaborate, scientific guidelines for how to mix favorite colors and how to apply them. Yet ordinary mortals who have only once done an entire painting in one sitting, alla prima, know how magical the process can be when it turns out exceedingly well. What goes into these results, what produces them, remains mysterious: a certain intense quality of attention, a compelling desire, a hunger, to put certain colors in certain ways on a canvas, a certain level of pleasure in the unfolding results that intensifies the desire, and so on, all of which have as much to do with unrepeatable happenstance as they do with conscious control over the process itself. In other words, it’s a state of flow, which is as difficult to achieve as a great painting–they are one and the same, the flow and the outcome of it. Yes, years of practice and discipline make it possible. Yes, it’s the outcome of rules and intentions. But no, it is not without dozens or hundreds of unpredictable and happy accidents, unrepeatable because they weren’t learned and can’t be taught. What’s most crucial in a great painting isn’t the outcome of empirical knowledge and can’t be predicted: otherwise you could teach anyone with a certain level of skill how to make a great work of art. The act of painting can also involve moments of despair when the entire thing seems hopeless and lost only to emerge again in success–by misdirections you find your direction, to paraphrase Hamlet. None of which is predictable. The unintentional results, the moments and outcomes that surprise the artist, as well as the viewer, are what make painting such a life-affirming calling, why it is a quest, not a job.

There’s a great summary of John Cage’s approach in the essay:

What is distinct in Cage, and something difficult but not impossible for a visual artist interested in “chance” to capture, is that in Cage’s “chance” works—e.g., Music of Changes (1951), Two Pastorales (1951-2), Seven Haiku (1951-2), For M.C. and D.T. (1952)—Cage utilizes a compositional tool over which he does not have control. In 1958, Cage introduced his ideas regarding indeterminacy in Darmstadt, Germany, in a lecture entitled “Composition as Process.”[1] At this period of his life, Cage had discarded the ideas and methods underlying his earlier compositions, which had included: numerical structures, considered improvisation, unambiguous notation, and preconceived form. In this lecture, Cage presented his ideas of “non-intention.” In “Composition as process,” Cage lectures on composition that is indeterminate with respect to its performance, remarking that:

“… [t]hat composition is necessarily experimental. An experimental action is one the outcome of which is not foreseen.”[2]

“… [t]he early works have beginnings, middles, and endings. The later ones do not. They begin anywhere, last any length of time, and involve more or fewer instruments and players. They are therefore not preconceived objects, and to approach them as objects is to utterly miss occasions for experience.”[3]

“… constant activity may occur having no dominance of will in it. Neither as syntax nor structure, but analogous to the sum of nature, it will have arisen purposelessly.”[4]

If Cage aims at music which is unforeseen and purposeless, it is because this music is free from the intentions and expressions of the composer’s mind. But this is not something simply left up to improvisation—for one’s “feeling” of being a conscious driver of their artistic process does not mean that they are not acting out of intention, wittingly or not. Thus, Cage implemented models for the realization of this kind of music.[5]

Chance in music, and in visual art, cannot simply “happen” due to the improvisational whims of the artist and their “feeling” of not being in control. It is necessary to provide a mechanism within which it will operate. Thus the composer of a “chance work” or the artist of a “chance painting” must first design some system in which chance has a role to play. A system must therefore provide for certain “givens,” or fixed elements: e.g., collections of musical materials that are to be manipulated, such as the overall structure of the work. This system must have a collection of rules or procedures to be followed so as to produce the final score (or painting), where these rules draw upon the given materials and structures to make decisions based on some random factor, such as the toss of a coin or a computer-generated random number.

Designing the system in which chance has a crucial role in the outcome is not the same as controlling the outcome, nor does it create the other extreme, where the results are entirely random. Painting is a balance between intentions and fortuitous accidents. The optimum spiritual or mental state for an artist to achieve while painting is a perfect balance between what can be predicted and repeated and what cannot–like a surfer staying upright on an enormous wave. What makes a painting strong, up to a point, can be duplicated again and again–what makes it great is another matter entirely. And that factor may not entirely be aleatory, but it can’t be controlled. It’s a gift.

June 22nd, 2021 by dave dorsey

Woman in White, Picasso, oil on canvas, 1923

If you can say what beauty means, then you’ll be able to explain what any great painting means. But, as Iris Murdoch observed, the more clearly you see beauty, or truth, or goodness, the more mysterious it becomes, the more inaccessible to the easy manipulations of reasoning–and the more it becomes something you serve rather than understand and control.

The reactionary, neoclassical work Picasso did after the cataclysm of World War I represents his greatest and most heartfelt struggle to capture what drove him to paint again and again: the beauty and allure of women. He expressed this in so many ways, some far more impressive in hindsight than others. In the neoclassical work, his only showmanship was in easy ability to convey profound gratitude through a series of edges drawn with brilliant, childlike simplicity and proportion. I came upon this example during my visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art recently. Every time I see work like this from the past, I feel I’ve never really fully appreciated it until now, which is exactly how I felt when I saw another example of this period and style from Picasso at my last visit to LACMA . In such a delicate image, I am always surprised, up close, to see how rough he could be in the way he applied the paint, applying it more like joint compound or spackle, smeared, scraped, and generally handled with expedience and no regard whatsoever for how the marks will look up close. Velasquez and Sargent would weep at his heedlessness, and I almost did as well, but not in disappointment. Picasso’s gift was nearly unique, a line as rare as Ingres, but there’s so much more heart here, so much more of a surrender to the essential mystery of what he’s yearning to show you. Beauty like this silences you on the spot, this post notwithstanding.

Anyone who wants to understand Picasso’s comment, sent along to me months ago by Bill Santelli, about the meaning of painting has only to look at Woman in White to understand that a great painting can be utterly meaningless and also the embodiment of everything you most need to see:

Everyone wants to understand painting. Why not try to understand the songs of a bird? Why does one love the night, flowers, everything around one, without trying to understand them? But in the case of painting people have to understand.

From Christian Zervos, “Conversation avec Picasso” in Cahiers d’art, 7/10, Paris, 1935, p. 178

June 19th, 2021 by dave dorsey

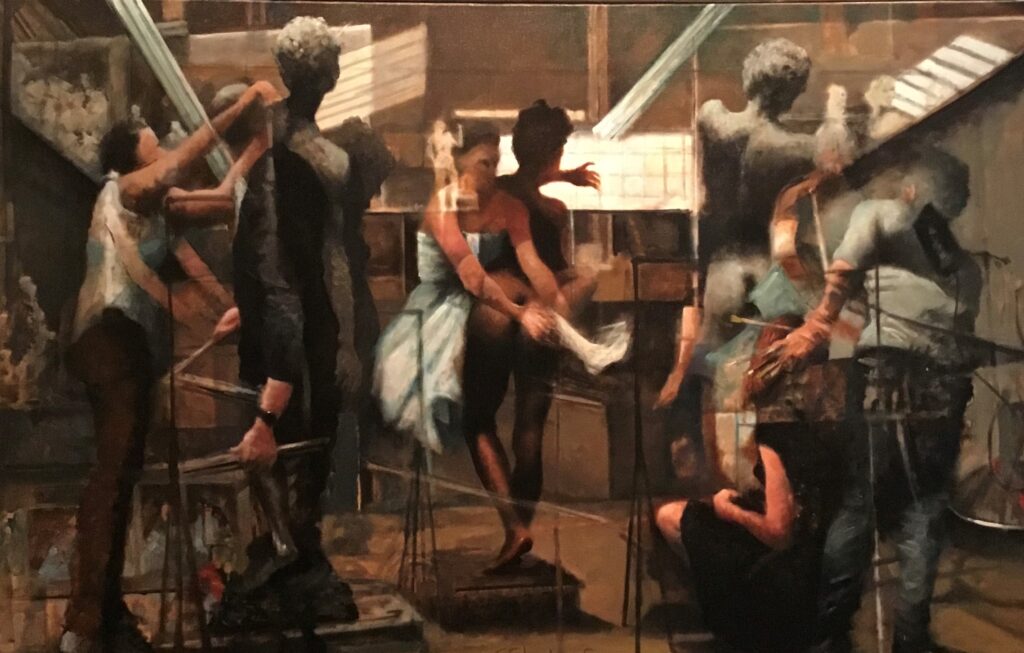

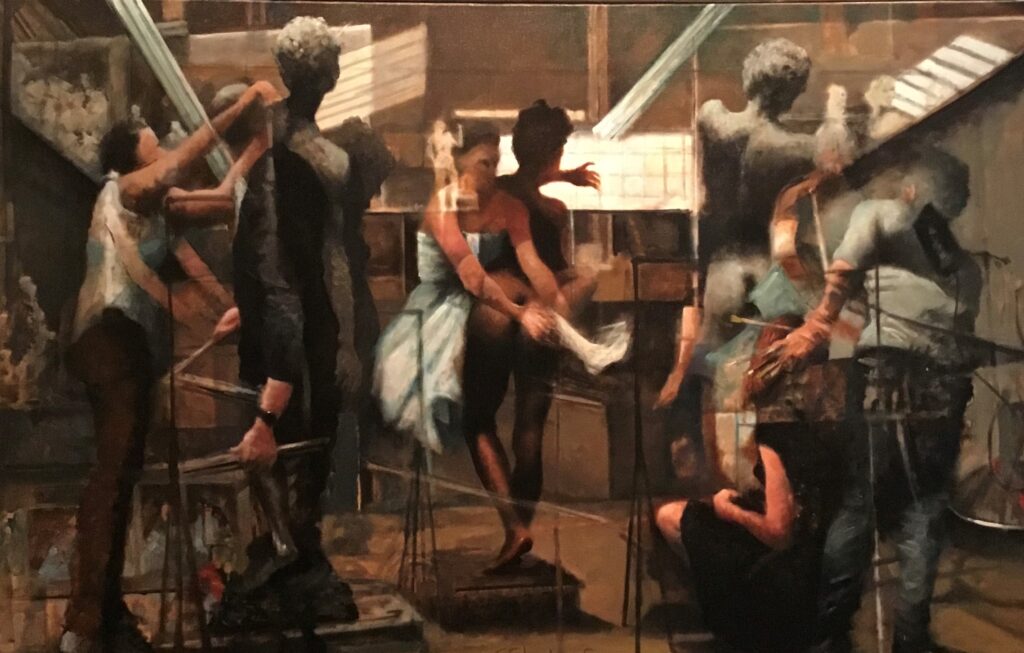

Tom Insalaco, one in his new series of studio paintings

For quite a while now, Tom Insalaco has been working on a suite of paintings that remind me of the world Braque inhabited–both pictorially and spiritually–at the culmination of his career when he was painting abstract images of his studio. Braque spoke in his notebooks about transformation as the essential thrust of painting: to take what’s seen and magnetize paint around the imagery the visible world lodges in your soul. Insalaco has immersed himself in painting after painting of artists at work in various studios, finding sources in films on the Internet and then transforming what he observes into what could be interpreted literally as double-or-triple exposures, scenes superimposed upon one another. But he’s after something outside time and space, indefinable, one’s true life, in accessible to the daily conscious mind. And focusing on the studio as the portal, a window, into this extra-temporal reality, he’s trying to get at why we paint at all. It isn’t to change the world. It’s to witness what’s actually there, everywhere, inaccessible to our chattering, busy minds. Of course, every painter I know and love is trying to do exactly the same thing, but in his or her own way.

Here what appears to be a dancer either stretches or practices in the center of the painting. Layered over this, a remote scene of a performance on stage, a singer or actor, like a remote, lonely puppet, and finally what gives the painting its structural coherence, a studio where two sculptors are working from a nude male model. What’s easy to miss is what appears to be a little quote from Velasquez, as it were: a slightly jumbled hint at Las Meninas, maybe the greatest studio painting in Western art. Insalaco didn’t consciously put that there, but he saw the unintentional reference himself, when I pointed it out. The seated woman in the foreground seems part of the scene with the dancer. Everything melds together into a unity that has its own dreamlike disengagement from familiar time and space, which is Insalaco’s true north, the disorienting transcendence of the surrealists, but closer to Chagall’s ecstatic Cubist-influenced dreams of his love for Bella, his heart’s home, where gravity knocked but never got in. Time here is Proustian, and space is both as small as the amount occupied by a mosquito arrested in amber and as large as the Milky Way.

June 16th, 2021 by dave dorsey

Social Network, Bernard Siciliano, oil on canvas, 2019, 76″ x 100″

I had an exhilarating visit to Manhattan three weeks ago. It’s been a year and a half since I went into the city to see the Salinger relics, as it were, at the New York Public Library. (I have yet to finish a post about that, though it’s nearly done.) The pandemic started a few weeks later and the world seemed to come to a halt. Time stopped. It has restarted. On my weekend in the city, things were hopping, much more alive and back up to speed than I’d thought the place would be. Saturday foot traffic was actually pretty heavy throughout Chelsea and SoHo. Midtown, where I stayed a couple nights, was sketchy and a little weird, as if the idleness of the pandemic drew people into stagnant eddies in alcoves, on corners, everyone just idling in public, harmlessly enough, people discarded by that more purposeful river of humanity to the north and south. Trash everywhere was overflowing nearly every visible container. That New York scene of urine was detectable at regular intervals. A mile uptown, in Central Park and along Fifth Avenue, as well as on the West Side, things seem quietly jubilant and populous.

The galleries were open but not packing anyone in—in other words, back to normal, but with masks. Zwirner had plenty of visitors, but I didn’t want to stick around. Ray Johnson’s solo exhibition was amusing. The motto on the wall as you walked in: “If you take the cha-cha out of Duchamp you get what a dump.” On display in a glass case were some rubber stamps he’d created that made me laugh. With them you could ink some labels onto an envelope or sheet of paper: Collage By A Major Artist, Toilet Paper, Odilon Redon Fan Club. Somebody could make some extra money with an extensive line of rubber stamps in that vein, if people only used paper to communicate now. I spent most of my time at Arcadia, Meisel, Hauser and Wirth, Paul Kasmin and wherever I could find representational painting of one sort or another. Much of what I saw in the galleries I visited was rewarding and, in the galleries I didn’t check out, much of what I could see through the windows seemed clearly avoidable. I caught the last day of the curated group show of figurative painting at Sugarlift, which was the highlight of my weekend. If Sugarlift can make a go of it in Manhattan, after holding its own in Brooklyn, good things remain possible in the world of painting. I rode the elevator up at Pace (what next, an escalator like the ones at Target a few blocks away?) to see the Agnes Martin show, a selection of nearly all-white stripes with only one or two bearing the faintest colors. I felt as I’d felt seeing her retrospective at the Guggenheim. She’s such an enigmatic figure, her abstraction seems intensely personal, cherishing her Platform Sutra, periodically living in isolation, creating one horizontally striped canvas after another, paintings that seem to belong at Dia Beacon next to Robert Ryman. Somehow, though, they are more poetic and wistful, albeit almost as minimal. Why her painting works this way for me, I have no idea, other than the general mystery of painting and what undetectably goes into it and then comes back out. Yet again I was struck by how idiosyncratic her paintings felt, the lines she seemed to have drawn free-hand in graphite to define the stripes, so that the pencil meandered like a lady bug leaving a trail around the little irregularities in the surface, a tiny trickle of graphite (it would appear) that looked serpentine from a few inches away but straight from six feet. Seeing a small collection of her work on view together, the repetitiveness, the sense of slight variations within the confines of a voluntarily apophatic format, gave me courage to keep painting my repetitive images of taffy, seeing where it will lead. (But the work proceeds so slowly, like Issa’s snail. I told Tom Insalaco when I went to see him in his studio last Friday that doing this series takes so much time, it feels like trying to sprint through a swamp.)

My visit to the Metropolitan on Sunday, more than at any previous time, made me feel as if I hadn’t ever understood paintings I’ve looked at many times before, either there or in reproductions. Again and again I thought, I’ve never really seen what was going on in this painting as clearly as I do now. It’s a great state of awareness, to look with that kind of fertile attention, especially in that museum. I spent a lot of my time in the gallery spaces devoted to the evolution of Degas, an artist I’ve begun to admire more and more, though I hardly gave him any attention when I was younger. It was humbling and awe-inspiring to see him grow from a conservative realist to a man who succeeded in getting pastel to do things it hadn’t done before through candid and intimate images of women rendered in long parallel single-hatch marks. But these long lines of color, furrows almost, with the gauzy effect of pastel rather than the crisp marks in a Durer, say, using the tools of drawing or print-making. Those parallel lines that surfaced and receded across the image gave it a vibrating energy, a pulse, that worked in counterpoint to the soft, diffuse light pastel typically gives off. Seeing his transformation from earlier and brilliant academic work to these late, radiant studies drenched in rich color, as I moved from one work to the next, was like watching a caterpillar shape-shift into a butterfly in a time-lapse film.

I had dozens of surprises like that: a Lee Krasner that was reminiscent of Matisse, painted a decade or so before she died; a de Kooning that, up close, revealed that he’d pressed newspaper pages into his gesso, or whatever ground he was using, to leave a ghostly image of the words and pictures pulled from the newsprint, reversed, the way kids once did and maybe still do with Silly Putty; a pair of worn shoes from Van Gogh that reminded me of Heidegger’s famous quote; a vertiginous overhead view of a long table and floor from Sheeler that was part of my inspiration for the series of large tabletop still lifes; one of Braque’s great paintings from his middle period, along with the gueridons, a pool table also seen from directly above, but shaped like an hour-glass; one of the Ocean Parks from Diebenkorn; and maybe my favorite paining from Cezanne, View of Domaine Saint-Joseph, a painting closer to the work of the Impressionists than most of what he did, but with an utterly unique sense of color. He knew how to create a network of marks across a canvas, where every spot of color lives in its own subtle purity, no going-over, no pentimento, once and done, each mark unique—creating maybe the most complex and lovely greens of any landscape ever painted—and yet despite all that energy and perfection in the mark-making, considered on its own, it also serves to convey the humming, brilliant energy of a summer day in the hills. The Metropolitan was full of people. The line for the Alice Neel show was half an hour long, according to the guard. Skipped it, but nice to see things are heating up. All that waiting-in-line patience has been honed by deprivation, probably. On the other hand, the guard told me that shows in the near past have drawn lines that snake out the front door and around the block.

I got the distinct impression that right now might be a rare opportunity for a gallery that wants to open or re-open in New York. For years now, art galleries have had to make more and more money to remain operational in Manhattan. George Billis has left, moving his space to Westport. OK Harris closed a while back, though not simply because of the cost of renting the gallery space. Danese/Corey ended its brick-and-mortar exhibitions, which felt like another Gotterdammerung blow to anyone who longed for islands of sanity and taste in the anarchic and often underwhelming sea of visual art. Five years ago, Steven Diamant packed up and left his gallery in New York to open exclusively in Los Angeles, first in Culver City and then in Pasadena. Both of those locations looked bigger and brighter than the one he’d had in SoHo. He spent five years trying to adapt to California. When I came into the gallery he was in his office, available to visitors as always. I asked about his move back to New York and he said he hated California. I went down the checklist sardonically, after he said he didn’t do yoga. Sushi? Never eats it. Pilates? As if. Charlie don’t surf, and I gather neither does Steve. I found him, as usual, on site in his office, there to answer questions and talk about the show, and his other artists. And this is where he told me some things that ought to signify a little inflection point for the art scene in Manhattan—or maybe a window of opportunity this year, at least. He said that his location is far better than he’d ever had in Manhattan and his exhibition space on W. Broadway at the edge of SoHo is now larger than any space he’s previously had and yet the rent is lower than what he paid twenty years ago.

People should be flocking back and locking in long leases. In major cities and across the country, the real estate mania is driving inflation in housing prices—even as commercial real estate looks more and more like a graveyard for burying cash. The pandemic drove people out of the cities, many of them for good, and is still driving them out, because so many city dwellers learned they can work remotely. Offices are emptying out. The pleasant surprise is that, commercial real estate is getting cheaper. It would seem to be the time to get a deal and open galleries like Sugarlift, dedicated to genuinely good new art, for those who love good art, rather than investors seeking an alternative to precious metals. To put it precisely: do all the gallerists out there realize that this represents an opportunity to move back into a prime location at a much lower rate than before? This undoubtedly won’t last, with all the money the government is pumping into the economy. But, as the city opens back up, maybe some galleries can move back in.

June 13th, 2021 by dave dorsey

Detail from The Healers, Ali Banisadr, oil on linen

After a year and a half of not having crossed a bridge or driven through a tunnel into Manhattan, the most impactful exhibit I saw on my quick tour of Chelsea and SoHo two weeks ago was Ali Banisadr’s work at Paul Kasmin on W. 27th. The Iran-born Brooklyn painter has found a way to tap into the period when European Surrealism morphed into American Abstract Expressionism, and by re-inhabiting that fertile sea change, he’s uncovered something exceedingly rich and strange. In a way, he’s put himself back into the same position as Arshile Gorky, halfway between the two movements, exploring missed opportunities that could have emerged then, using the fulcrum this gives him to create his own eerie and strangely riveting canvases that have more than a little in common with Gorky’s.

Banisadr paints slow-motion and silent battlegrounds or communities of unnatural creatures, the spiritual equivalent of a Star Wars cantina. They’re the sort of beings a feverish child fears or covets in the closet or under the bed at night, little exotic pet-like entities with no recognizable morphology. They don’t look fierce; but they don’t look innocent either. Soft maybe, but not cuddly. They’re too uncanny to completely trust, more like random mutations of a fantasy video game cast or some occult catalog of spirits. It’s as if Hieronymus Bosch had returned and found a new way to embody human impulses as creatures from a weird children’s storybook. Yet there’s none of the repellent suffering you see in Bosch; instead, everything is as quiet and lovely as life in a tropical fish tank under black lights.

The Healers

These scenes lure you with the pleasure of their silky transitions from one rich color to another, the energy of their execution, the velvety quality of the paint that looks as if the support itself is plush and black. Everything seems to emerge from that black ground. What you see at first is just the quality of the paint—smeared, speckled, striped, MORE

June 10th, 2021 by dave dorsey

Lacoon, Julio Reyes, egg tempera on panel, 16″ x 16.5″

You have a few more days to catch the exhibit of egg tempera paintings from Julio Reyes at Arcadia on W. Broadway in SoHo. They are well worth the visit. He has an ability to use figurative painting to convey internal states of mind and heart. He searches for objective correlatives, as T.S. Eliot referred to the poet’s quest, for these complex internal worlds. Some of his oils are included in the show, but mostly you’ll see his recent efforts in this medium that’s been around far longer than oil. Steve Diamant, who is almost always at the gallery when it’s open and ready to offer commentary on the artists he has chosen to represent for years–the old-school way– shook his head with admiration when I asked about the process. He said it’s arduous, time-consuming and requires the building up of an image through many coats of paint, mixed from pigment and raw egg yolks. The medium was used by artists as diverse at Botticelli, Thomas Hart Benton and Andrew Wyeth. Up close, the mark-making is a marvel. It’s essentially an impressionist technique, where Reyes builds up his forms through thousands of repetitive marks, but each one has its own distinctive and precisely defined shape. The images are luminous, dreamlike and suggestive of heightened states of perception and feeling, and the workmanship is masterful, personal, fully-realized.

shook his head with admiration when I asked about the process. He said it’s arduous, time-consuming and requires the building up of an image through many coats of paint, mixed from pigment and raw egg yolks. The medium was used by artists as diverse at Botticelli, Thomas Hart Benton and Andrew Wyeth. Up close, the mark-making is a marvel. It’s essentially an impressionist technique, where Reyes builds up his forms through thousands of repetitive marks, but each one has its own distinctive and precisely defined shape. The images are luminous, dreamlike and suggestive of heightened states of perception and feeling, and the workmanship is masterful, personal, fully-realized.

June 7th, 2021 by dave dorsey

New work from Bill Stephens

I sat down last week with Bill Stephens and Bill Santelli, outside Santelli’s home studio near Powder Mill Park. We talked for three hours about many things including my exhilarating recent visit to New York, and their work. I saw one older painting from Santelli hanging on his wall that knocked me out–I’ll post it next. Stephens sent me these two recent pieces, continuing evidence that he and his wife, Jean, are the most experimental painters I know at the moment. Their work continues to morph into new areas, sometimes gradually, but also abruptly and unpredictably. These two acrylics by Bill are marvelous in entirely different ways, the one Rothko-ish and the other drawing comparisons to Monet from Santelli. Yes, if Monet had been at the bottom of his water lily pond looking up toward a sunny sky . . .

May 24th, 2021 by dave dorsey

Zoey Frank, Pool Party, Oil on canvas, 114 x 96”

Art isn’t a contest. There are plenty of art competitions, yes, and there are hierarchies of talent, but the idea of scoring Piero against Giotto . . . what would that even mean? However, if painting were a competition, after seeing Zoey Frank’s current work, painters with a competitive itch might want to consider something comparatively easy as an alternative, like running a three-minute mile.

Frank is freakishly talented, a technical virtuoso whose work often has a cool, emotionally remote tone. Her chill facility hasn’t exactly been a hindrance. It was no surprise when Danese/Corey decided to sell her work. As I’ve followed her, I’ve often felt her greatest strengths were the ability to capture and convey fine gradients of inarticulate feeling—my favorite kind—where it’s almost impossible to distinguish between feeling and perception. She achieves this through her amazing discriminations of how light falls in different ways on objects depending on their distance from the viewer and position in a particular space. Her spaces seem quietly more alive than the objects that occupy them, her scenes hauntingly discernible, but in an indeterminate way.

She’s never content with representational prowess, constantly requiring the viewer’s visual understanding to flip back and forth between two and three dimensions, flattening her image into abstract patterns and then popping it back out into what’s easily identified, often without feeling the need to make the image entirely coherent. Much of this is at the core of what the perceptual painters tend to do, but she does it in an especially complex way, and the complexity often feels like something she has pursued for its own sake. Her surfaces are intensely alive, offering no place to rest. She gives her scenes an allover quality that dispenses with anything like a focal point, in the way a Persian rug greets the eye, but without its regularity and symmetry. She wants that middle ground between verisimilitude and geometry, but she also wants to create an almost Escher-like visual tension in a scene that often seems visually impossible so that the abstract and representational elements don’t quite abide each other. This strategy disorients the viewer, taking you out of familiar time and space, pushing you into a waking dream, vaguely nostalgic, that sometimes just flattens into a pattern that might as well be a strip of contact paper stuck to the canvas. With her, it’s sometimes like seeing the world whilst being a tad high on a controlled substance. It isn’t surrealism. She has none of that dark weirdness. Looking at her epic scenes of social gatherings, her teeming hives of cheerful and happy human activity, it’s more like remembering a sunny summer love-in from the Sixties than some episode from the subconscious. It isn’t about the recesses of the mind. She’s is an intensely outward-looking painter.

Her latest post on Instagram won me over. It’s one of the large paintings she will be showing, starting Thursday, at Sugarlift, a thrilling little operation, full of hope, piss and vinegar–the breakfast of all champion painters and gallerists–in its view of the current art scene. There’s a bit of Artsy in its business model, I think, but it has a new, cool brick and mortar space on W. 28th St. It seems to operate less like a traditional gallery and more like a continuous flash mob of quality painting outside the mold of the big white cubes where the most ridiculously priced work gets shown. (Pay a visit to Zwirner in Chelsea right now, if you want to see a depressing contrast of big money chasing diminishing returns for the viewer. It will intensify the glimpse of sanity that Sugarlift represents.)

MORE

May 8th, 2021 by dave dorsey

Through the Hedgerow, Jean Stephens, encaustic on board, 8″ x 8″

Jean Stephens has one of her newest paintings on view at the Annual Spring Member’s Exhibition at Mill Art Center and Gallery in Honeoye Falls. It’s a small landscape in encaustic, Through the Hedgerow, an example of how she’s working more loosely with her medium, with impressive results. It’s a more experimental phase for her, part of a transformation in her work over the past couple years, and she’s getting some remarkable results. The show includes the work of a couple dozen member artists, all of it interesting. Stephens also has an excellent figure drawing chosen for a national show at Main Street Arts, on view now as well in Clifton Springs, juried by Steffi Chappell, assistant curator at the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse. Both exhibitions close on June 11.

April 29th, 2021 by dave dorsey

Bartlett Pears, 12″ x 16″, oil on linen

My life the past two years has toggled between slow-burning family emergencies punctuated by intervals of regular, predictable daily hours of painting. The crises have morphed into ongoing obligations to care for family members who need assistance, but this is a shift toward regularity that allows me to restore the concentrated, monotonous, repetitive attention essential for painting. I’m finally emerging from unpredictable interruptions and, if I’m lucky, I’m hoping I can look forward to quite a few years of being able to put in significant daily hours of work. It’s what I need to finish a suite of paintings I started more than two years ago: images of salt-water taffy I haven’t been posting because I want to complete most of the whole series in order to decide what to put on view. I’ve completed only ten of these paintings so far—even the smaller ones have taken four to six weeks, with six weeks as the average for painting the largest of them. Even at that deliberate rate, I should have completed far more than ten, but for the entire summer two years ago while providing care for my father I was unable to sit at the easel and then I had several months helping my brother get my mom’s life in order in his absence. Then my son and daughter-in-law left California to stay here in Rochester during the pandemic, finally deciding to actually move here when Laura realized she could work remotely as a video producer—which Matthew may be able to do as well once they hire help for childcare. A freak automobile accident created a situation similar to what we faced with my father two years ago—but Laura eventually recovered enough for them to buy and move into a home a mile away. And then she had a baby, their second son. Her recovery and the new grandchild are a blessing, but also—in a wonderful way—it has provided fresh excuses to do things other than paint. All of this has prompted me to go dormant for periods on Instagram and this blog, still working pretty diligently, but not communicating much about what I’ve been doing. MORE

April 24th, 2021 by dave dorsey

Mark Tennant, untitled from Instagram

Mark Tennant ought to be understood as one of the perceptual painters, but he doesn’t really adhere to any of the half dozen implicit rules the hardcore members of that group observe: the delicate balance between flatness and the illusion of depth; the preference for middle values, the slight fetish for letting one’s process show through a palimpsest effect that, for example, allows the viewer to see pencil lines through thin layers of paint or ghosts of earlier and abandoned shapes; their willingness to repeatedly rework a surface, groping toward a final resolution; a preference for middle values; and a general avoidance of photography. Tennant doesn’t adhere much to any of this, but his work shows random glimpses of mundane life in a way that works as both representation and almost gestural abstraction, which seems the prime directive for most perceptual painters. Tennant always works, it seems, from snapshots. His paintings seem intensely immediate and present—an impression of human motion frozen by an explosion of light. The work of the perceptual painters seems closer to the indeterminacy of memory, its slightly faded moodiness, than to the crisp detail of what greets the eye here and now. Tennant’s work oddly toggles between past and present, but it seems to make the past look contemporaneous, rather than the other way around. The look of a snapshot evokes the past, by definition, but what you see in one of his paintings seems alive and ready to move, something that caught your eye fifteen minutes ago. He loves the baleful glare of flash photography and the way it gives relief to figures, nudging them toward the viewer by coating them with dark outlines, penumbras of visible shadow that often seem, by some inexplicable leap, to hint at moral decline.

What’s so remarkable about his paint is the way it looks fresh, spontaneous, alla prima, and yet so astonishingly accurate—each little painting is like a visual haiku, the scene reduced to the fewest possible descriptive details, a face nothing but spots of color with three tiny marks to indicate eyes and nose, no need to even indicate a mouth. But nothing looks all that worked over: he’s giving you just what’s there, minus all the information you simply don’t need. That’s classic painting, but it feels, in his hands, like something fresh and unfamiliar. (And that’s great painting.) So simply executed, yet that little face of the woman in the center of her cocktail party chatter, that visage the size of a fingerprint, would be instantly recognizable to anyone who knew her, whoever she is. How is that possible? The eyes—like the tiny eyes in a very small El Greco I saw in New York years ago—convey a whole world of personality and experience, a soul. But Tennant has nothing else in common with the Greek. There’s no transcendence here, just that unforgiving flash of light and the darkness it only briefly penetrates. At first, his brushwork seems to descend from Matisse and Porter, looking loose and bold, everything quick as a sketch. But he’s intensely accurate, and his sensibility is brooding and ironic. His process may be much slower than it looks, so the painterly effect probably goes back more to Manet and Sargent, where you have a sense of mastery closer to Velasquez than the Impressionists, and they share Tennant’s vision of how metropolitan sophistication draws some of its energy from decadence. Matisse and Porter use color and tone for their own sake, presenting the joy of natural light just as it is, reaching out and embracing the world with love and appreciation; Tennant inhabits a spiritual world as distant from theirs as Alaska is from Africa. Perhaps what continues to awe me with the work he posts is how much it has evolved and crossed some kind of qualitative border late in his career into this recent mastery. Decades of work leading to the alchemy of this transformation after so much effort: Porter crossed that border too in his last decade. You can see something similar happening as well in the work of some other painters, like Stuart Shils, on Instagram. It’s marvelous.

April 20th, 2021 by dave dorsey

There’s a nice video on YouTube about Philip Reed, a professional model builder: “a man who has committed his life to his craft; a lifetime of scrutinising detail, obsession, perfectionism, and in the end, something truly beautiful.” The short film is more reverential than instructive, if you want to know how he actually does what he does, but some of his comments in the video certainly resonate:

I remember Gerald Cooper, a very renowned painter. One day he just stood and looked at us for a while. He said, “I’m going to tell you the secret to happiness. Get up every morning and paint a flower before breakfast.” That is what he loved to do. So the first thing he did in the morning was that which he loved.

I think of them as three-dimensional paintings.

There are many times when little is achieved. There is frustrating research to be carried out and dead times when nothing seems to move forward. But then there are many others when the work just flows and you enter a very quiet space. Time passes effortlessly.

I go through very dark times sometimes. A recent model I’ve been building, every day has been struggle. It’s difficult. I need focus. The work is very fine. I don’t want to be there. But if you keep going you discover something new and suddenly it’s as if the sun’s come out and I’m loving what I’m doing again.

There are moments of excitement and pleasure when you start to see it come together. If you can get the tone, the color, and everything blend together, that final stage, working through it, is a joy.

Engaging in creative work can be, at its best, a mystical experience. I don’t know what is behind the creation of art. It’s something innate in man. It’s one of the profound mysteries in human life: creative work and art.

April 16th, 2021 by dave dorsey

Four Figs, Two Swans, and Pair of Scissors, 2017, oil on linen, 10.125 x 10″

Matt Klos invited me to sit in on a group Zoom last week with Susan Jane Walp, hosted by Klos and Candice Hill, who teaches in the English Department at Anne Arundel Community College, where Matt teaches painting. Walp has a quiet, distinguished career, living in Vermont, studying Tibetan Buddhism and painting and doing little else, having moved there from Soho where she worked in the 80s. It was a long, interesting conversation partly because so much of it felt attenuated by Walp’s difficulty in putting the most essential elements of what she does into words. That’s refreshing, a person of few words in an era where we live under a tsunami of social media inanity. A lot of the discussion was about a series of improvisational paintings she’s done as a meditation on the loss of her husband six years ago, paintings that somehow remind me of Jung’s The Red Book images, not in form but in spirit—as if she has been sketching emotional and spiritual archetypes drawn from her own subconscious. These are quite different from her core work in still life. What I found most useful was the discussion of these still lifes on linen.

The most interesting questions and answers were on how her work in oil resolves itself into something she considers finished; how she manages to keep the process feeling alive and risky after investing long days and weeks or months into a given painting; and what her primary considerations are, the core values, she tries to observe in the process of making a painting.

This last issue was very appropriate to this particular conversation, because Candice Hill specializes in lyric poetry with a focus on Emily Dickinson and found many parallels between Dickinson’s sidelong, elliptical poetry and Walp’s spare, improvisational watercolors. Walp has said she draws inspiration from Dickinson’s poems, their paradoxical sense of scale, particularly in Dickinson’s ability to evoke cosmic truth through such a tiny pillar of words on the page. That use of scale links her with Dickinson: the leverage involved in using something small to evoke something big. Walp’s paintings feel in some ways even smaller than Dickinson’s gnomic lines. Walp said: “Even in these paintings that are quite small, eight inches by eight inches, if that relationship becomes accurate (between the precise detail and the more indefinite lines of larger areas), I feel there’s something big about the painting.” Given this indebtedness to poetry, it wasn’t shocking that Walp cited Elizabeth Bishop, who was a serious painter as well as a uniquely great poet, as someone who perfectly articulated the three qualities creative work must have. Bishop said every poem needs to be accurate, spontaneous, and mysterious. Walp wants her paintings to hew to those rules.

There is a tremendous tension implicit in those first two qualities. How to be both improvisational and accurate seems to be a core competency for perceptual painters in general and a difficult tightrope to walk for any painter. (Fairfield Porter managed to balance accuracy and spontaneity perfectly again and again toward the end of his career, but Walp’s work doesn’t owe much to the way Porter handled paint, except in a few instances.)

Walp said: “In Dickinson the thing that has struck me in my non-scholarly reading of her work is the way that she can go from some very almost microcosmic detail to just the macrocosm. This idea of scale; how there can be an infinite space in such a physically small poem. That’s something I aspire to certainly in the still lifes . . . Bishop’s . . . three criteria for evaluating poems: accuracy, spontaneity and mystery. I’ve spent a lot of time working on the spontaneity. The mystery is divine grace. It’s given to you in certain work.” MORE

April 5th, 2021 by dave dorsey

The Garden of Earthly Delights, Agnieszka Nienartowicz

The ultimate tramp stamp. Amazing work from a young Polish artist, evoking both Bosch and Richter, with a cautionary twist to the allure it conveys.

April 1st, 2021 by dave dorsey

Vermeer’s “View of Delft”

I find it encouraging that the greatest philosopher and the greatest novelist of the 20th century agreed about some fundamental, crucial things, at about the same time, early in the century. It seems everyone else except maybe T.S. Eliot were heading in the opposite direction—Nietzsche a bit earlier, the modernists in art, Einstein in physics, Freud in his field, Marx in economics and politics–all of them striving to destabilize the values and norms of the Western world. Meanwhile, Wittgenstein and Proust were suggesting that the most fundamental realities hadn’t changed at all and would never change, even though many didn’t understand this about the philosopher, and it this isn’t immediately obvious in Proust, given the structure of his virtually plotless novel, a tapestry of interwoven stories that evolve almost imperceptibly toward his majestic renunciation of society in favor of art.

Wittgenstein, whose efforts have been camouflaged by his role as the patron saint of analytical 20th century philosophy, asserted that human values can’t be derived from our experience in the world. They exist outside the world, and thus, in a sense, can’t be analyzed or deduced, but are simply a given, transcendent and immune to rational justification or questioning. They have no utility. They just are. You don’t “adopt” them to make the world a better place (on what grounds would one chose a set of values that give you the rules for calculating which values are best?). Goodness is an unassailable framework within which human purposes evolve and can be understood. Goodness and truth and beauty govern human behavior, as the essential structure of human experience, whether or not an individual is conscious of them or not. In other words, Wittgenstein actually had a metaphysics, about which he forbade himself to talk, because its truth was impossible to prove, hence the famous last line of the Tractatus: “Whereof one cannot speak, one must remain silent.” However, he meditated quite a bit on these values during that silence. He carried around a copy of Tolstoy’s The Gospel in Brief all through his service in World War I, and he relinquished one of the largest inheritances in Europe. He seriously considered becoming a monk at one point. These transcendent values he lived, rather than asserted, because he appeared to consider them impossible to justify through reason or philosophical language. His silence about everything that actually mattered seems, in retrospect, almost uniquely noble and honest.

One finds a similar point of view, an even more Platonic one, from Marcel Proust in A La Recherche du Temps Perdu, written during the years Wittgenstein wrote his Tractatus, about the death of Proust’s fictional novelist, Bergotte. In The Captive, he talks about the role of the creative imagination, in painting and fiction and music. These thoughts precede one of the great revelatory moments in the story, when Morel’s musical performance triggers for the narrator a crucial moment of enlightenment about the nature of art. (It is typical of Proust that Morel is one of his few genuinely evil characters, the embodiment of sadistic cruelty, yet he is also, despite his depravity, a rare musical genius, one of God’s messengers, as it were, through the medium of the violin.) This passage makes Proust’s narrator sound a bit like a Cathar or a Buddhist, but his essential point is that human beings don’t pick and choose their “values;” those values precede and ground all human choices and behavior, and people spend their lives struggling to simply see them and exemplify them as directly as possible, to live “beneath the sway of those unknown laws”—an achievement that is, like a great golf swing or a sumi-e painting—both unconscious and ego-less, almost automatic, when done perfectly, and yet immensely difficult to “get right”:

He was dead. Dead forever? Who can say? . . . All that we can say is that everything is arranged in this life as though we entered it carrying a burden of obligations contracted in a former life; there is no reason inherent in the conditions of life on this earth that can make us consider ourselves obliged to do good, to be kind and thoughtful, even to be polite, nor for an atheist artist to consider himself obliged to begin over again a score of times a piece of work the admiration aroused by which will matter little to his worm-eaten body, like the patch of yellow wall painted with so much skill and refinement by an artist destined to be forever unknown and barely identified under the name Vermeer. All these obligations, which have no sanction in our present life, seem to belong to a different world, a world based on kindness, scrupulousness, self-sacrifice, a world entirely different from this one and which we leave in order to be born on this earth, before perhaps returning there to live once again beneath the sway of those unknown laws which we obeyed because we bore their precepts in our hearts, not knowing whose hand had traced them there—those laws to which every profound work of the intellect brings us nearer and which are invisible only—if then!—to fools. So the idea that Bergotte was not permanently dead is by no means improbable.

–The Captive

February 25th, 2021 by dave dorsey

From Jim Mott, this little passage from a short story about a painter by Chekhov. It conveys to me, like many landscapes described by Proust in his novel, exactly why someone would develop a passion for landscape painting:

Doomed by fate to permanent idleness, I did positively nothing. For hours together I would sit and look through the windows at the sky, the birds, the trees and read my letters over and over again, and then for hours together I would sleep. Sometimes I would go out and wander aimlessly until evening.

Once on my way home I came unexpectedly on a strange farmhouse. The sun was already setting, and the lengthening shadows were thrown over the ripening corn. Two rows of closely planted tall fir-trees stood like two thick walls, forming a sombre, magnificent avenue. I climbed the fence and walked up the avenue, slipping on the fir needles which lay two inches thick on the ground. It was still, dark, and only here and there in the tops of the trees shimmered a bright gold light casting the colours of the rainbow on a spider’s web. The smell of the firs was almost suffocating. Then I turned into an avenue of limes. And here too were desolation and decay; the dead leaves rustled mournfully beneath my feet, and there were lurking shadows among the trees. To the right, in an old orchard, a yellow hammer sang a faint reluctant song, and he too must have been old. The lime-trees soon came to an end and I came to a white house with a terrace and a mezzanine, and suddenly a vista opened upon a farmyard with a pond and a bathing-shed, and a row of green willows, with a village beyond, and above it stood a tall, slender belfry, on which glowed a cross catching the light of the setting sun. For a moment I was possessed with a sense of enchantment, intimate, particular, as though I had seen the scene before in my childhood.

By the white-stone gate surmounted with stone lions, which led from the yard into the field, stood two girls. One of them, the elder, thin, pale, very handsome, with masses of chestnut hair and a little stubborn mouth, looked rather prim and scarcely glanced at me; the other, who was quite young–seventeen or eighteen, no more, also thin and pale, with a big mouth and big eyes, looked at me in surprise, as I passed, said something in English and looked confused, and it seemed to me that I had always known their dear faces. And I returned home feeling as though I had awoke from a pleasant dream.

February 22nd, 2021 by dave dorsey

Evelyn Waugh

From Brideshead Revisited:

Restrained by this wariness I asked him nothing of himself, but told him, instead about my autumn and winter. I told him about my rooms in the Ile Saint-Louis and the art school, and how good the old teachers were and how bad the students. ‘They never go near the Louvre,’ I said, ‘or, if they do, it’s only because one of their absurd reviews has suddenly “discovered” a master who fits in with that month’s aesthetic theory. Half of them are out to make a popular splash like Picabia; the other half quite simply want to earn their living doing advertisements for Vogue and decorating night clubs. And the teachers still go on trying to make them paint like Delacroix.’ ‘Charles,’ said Cordelia, ‘Modern Art is all bosh, isn’t it?’ ‘Great bosh.’ ‘Oh, I’m so glad. I had an argument with one of our nuns and she said we shouldn’t try and criticize what we didn’t understand. Now I shall tell her I have had it straight from a real artist, and snubs to her.’

February 19th, 2021 by dave dorsey

K.81 Combo, 3D painted sculpture, Frank Stella

I’ve been frustrated for years by my fruitless search for a catalog of Frank Stella’s work that gives the reader a comprehensive view of his gorgeous protractor series of minimalist abstractions in the 60s. I long to see the colors of those paintings reproduced as accurately as possible in a book, and especially in a retrospective devoted only to that series. To see those paintings assembled together, all on their own, would be worth the effort. Most of his career represents a repudiation of Clement Greenberg’s elevation of “flatness” as the defining characteristic of painting, an axiom that seems more and more irrelevant, even silly, with time–and now in retrospect seems even more to miss its target when applied to the painters he was trying to glorify. Rothko’s paintings are certainly a flat surface, but their simple glowing colors recede and advance as the tones of earth and sky do in a landscape, and that illusion of depth gives them part of their somber allure. They invite you to step in, toward that horizon line. After the austerity of the black and metal paintings, in which he constructed shaped canvases at least partly to defy Greenberg’s dictum, Stella embarked on a long exploration of color harmonies in a surrender to flatness, more or less. Many were shaped, but they worked because of color applied in flat patterns on a flat surface. Their lyrical restraint was what made them so charming. For me, they are distinguished by the thin gutter between each straight or curved stripe, a little buffer of white between each designer tone that allows each individual color to respond to the ones around it cleanly and distinctly.

I was reminded of these wonderful paintings–painted in a spirit of what I would consider mid-20th century abstract version of neo-classicism–serene and vibrant despite the relentless geometric order of their flat patterns, a celebration of Athenian moderation and order after the sturm und drang of AbEx. They were another avenue, along with Pop, for a rejection of the grim seriousness of the 50s. Why so serious, painters in the 60s seemed to be asking, but with a smile less violent than The Joker’s. Stella’s protractor designs are a celebration of art’s ability to manifest joy, as Dave Hickey’s last sentence does in The Invisible Dragon: “Beauty is and always will be blue skies and open highways.” It’s a sentence so full of the promise of America half a century ago, when Hickey immersed himself in the art world, when we were building a launch pad to fire ourselves at the moon and bringing civil rights to those who had never had it before. America–and Stella’s paintings along with it–felt like a launch pad for an unlimited future. Those protractor paintings are a visualization of happiness and possibility untainted by resentment or anxiety. The global economy hadn’t arrived just yet to erode the burgeoning American dream by narrowing it to exclude those who don’t have a share of Wall Street largesse. Stella’s brief Apollonian phase continues to be a reminder that human life can be a balance between head and heart, math and emotion, open roads under that beckoning, unattainable blue sky.

In my fruitless search for such a catalog of those late 60s paintings, I came across one of his much more recent baroque constructions, included in the Whitney retrospective a few years ago: K.81 Combo (K.37 and K.43) Large Size. It’s a continuation of his Sixties ebullience, by other means, in three dimensions. Stella considers it a visualization of a Scarlatti sonata. In three dimensions, and with color as delightful as a series of life-affirming musical tones, he is bringing what the color field painters did in the 60s into a branch of sculpture. It takes the fountain of interwoven counterpoint that is Baroque music and uses it as an imaginary armature for the construction of brightly colored surfaces that seem to swirl outward and back into themselves like orderly solar flares. As I gazed at the reproduction of Stella’s sculpture, I was struck by how it’s doing something I’ve been trying to echo in my current paintings of salt water taffy.

I think of these paintings as portraits of a highly simplified, three-dimensional color field painting, as if someone had taken a painted canvas and crumpled it into a ball and then let it expand randomly into its final punished shape–all the spirals and glowing quadrants of color deformed and fused into a lump and then wrapped in translucent waxed paper, giving the patterns of color a diffuse, glowing, partly concealed quality. In the shards of translucent paper that surround the candy and flare outward at each side like wings, I’m establishing patterns and lines, whorls and dents and fissures, that repeat and connect in unexpected ways, as the lines in a Braque gueridon do. Before I ever pick up a brush, I create much of these formal qualities, the composition itself, with my fingertips. I often unwrap the taffy and rewrap it myself with waxed paper from the kitchen. I try to gently twist the wax paper (I cut it to precise dimensions) so that it wrinkles it as little as possible while preserving the curved planes. As I’m doing this, I create the object I will work from, building this uniform “armature” for color in the painted image. As I paint flat patterns of tones I will rework with greater and greater detail, I feel the spirit of a dozen previous painters whose work I love flicker through the process. It’s as if the painting goes through its Milton Avery and Braque period when it’s a flat pattern of uniform color and then emerges as a greatly enlarged single object still life–but it’s a still life of three-dimensional chunks of candy making patterns that remind me mostly of color field painters from half a century ago. As I was doing in my candy jar paintings, and intend to do again in future ones, I’m constantly drawing energy and desire from the qualities of those modernists: Stella, Noland, Hammersley, Avery, Frankenthaler, Francis, and so many others, painters whose work became a sort of visual equivalent to music.

shook his head with admiration when I asked about the process. He said it’s arduous, time-consuming and requires the building up of an image through many coats of paint, mixed from pigment and raw egg yolks. The medium was used by artists as diverse at Botticelli, Thomas Hart Benton and Andrew Wyeth. Up close, the mark-making is a marvel. It’s essentially an impressionist technique, where Reyes builds up his forms through thousands of repetitive marks, but each one has its own distinctive and precisely defined shape. The images are luminous, dreamlike and suggestive of heightened states of perception and feeling, and the workmanship is masterful, personal, fully-realized.

shook his head with admiration when I asked about the process. He said it’s arduous, time-consuming and requires the building up of an image through many coats of paint, mixed from pigment and raw egg yolks. The medium was used by artists as diverse at Botticelli, Thomas Hart Benton and Andrew Wyeth. Up close, the mark-making is a marvel. It’s essentially an impressionist technique, where Reyes builds up his forms through thousands of repetitive marks, but each one has its own distinctive and precisely defined shape. The images are luminous, dreamlike and suggestive of heightened states of perception and feeling, and the workmanship is masterful, personal, fully-realized.