Archive Page 8

February 16th, 2021 by dave dorsey

C.S. Lewis

C.S. Lewis, from The Abolition of Man, a passage that serves as a commentary on post-modernism, before there was such a thing, and how all moral imperatives ultimately are based on values that are accepted as “given” rather than individually chosen or invented, or culturally determined. What’s good is ultimately good in and of itself and not because certain individuals or groups of individuals chose it or enjoy it or invent it:

In their second chapter Gaius and Titius quote the well-known story of Coleridge at the waterfall. You remember that there were two tourists present: that one called it ‘sublime’ and the other ‘pretty’; and that Coleridge mentally endorsed the first judgement and rejected the second with disgust. Gaius and Titius comment as follows: ‘When the man said This is sublime, he appeared to be making a remark about the waterfall… Actually … he was not making a remark about the waterfall, but a remark about his own feelings. What he was saying was really I have feelings associated in my mind with the word “Sublime”, or shortly, I have sublime feelings’ Here are a good many deep questions settled in a pretty summary fashion. But the authors are not yet finished. They add: ‘This confusion is continually present in language as we use it. We appear to be saying something very important about something: and actually we are only saying something about our own feelings.’

The feelings which make a man call an object sublime are not sublime feelings but feelings of veneration. If This is sublime is to be reduced at all to a statement about the speaker’s feelings, the proper translation would be I have humble feelings.

The schoolboy who reads this passage in The Green Book will believe two propositions: firstly, that all sentences containing a predicate of value are statements about the emotional state of the speaker, and secondly, that all such statements are unimportant. It is true that Gaius and Titius have said neither of these things in so many words.

The authors themselves, I suspect, hardly know what they are doing to the boy, and he cannot know what is being done to him.

From this passage the schoolboy will learn about literature precisely nothing. What he will learn quickly enough, and perhaps indelibly, is the belief that all emotions aroused by local association are in themselves contrary to reason and contemptible.

Another little portion of the human heritage has been quietly taken from them before they were old enough to understand.

The differences between us may go all the way down. They may really hold that the ordinary human feelings about the past or animals or large waterfalls are contrary to reason and contemptible and ought to be eradicated. They may be intending to make a clean sweep of traditional values and start with a new set.

They see the world around them swayed by emotional propaganda—they have learned from tradition that youth is sentimental—and they conclude that the best thing they can do is to fortify the minds of young people against emotion. My own experience as a teacher tells an opposite tale. For every one pupil who needs to be guarded from a weak excess of sensibility there are three who need to be awakened from the slumber of cold vulgarity. The task of the modern educator is not to cut down jungles but to irrigate deserts. The right defense against false sentiments is to inculcate just sentiments. By starving the sensibility of our pupils we only make them easier prey to the propagandist when he comes. For famished nature will be avenged and a hard heart is no infallible protection against a soft head.

Until quite modern times all teachers and even all men believed the universe to be such that certain emotional reactions on our part could be either congruous or incongruous to it—believed, in fact, that objects did not merely receive, but could merit, our approval or disapproval, our reverence or our contempt.

‘Can you be righteous’, asks Traherne, ‘unless you be just in rendering to things their due esteem? All things were made to be yours and you were made to prize them according to their value.’

St Augustine defines virtue as ordo amoris, the ordinate condition of the affections in which every object is accorded that kind of degree of love which is appropriate to it. Aristotle says that the aim of education is to make the pupil like and dislike what he ought.

The little human animal will not at first have the right responses. It must be trained to feel pleasure, liking, disgust, and hatred at those things which really are pleasant, likeable, disgusting and hateful.14 In the Republic, the well-nurtured youth is one ‘who would see most clearly whatever was amiss in ill-made works of man or ill- grown works of nature, and with a just distaste would blame and hate the ugly even from his earliest years and would give delighted praise to beauty, receiving it into his soul and being nourished by it, so that he becomes a man of gentle heart.

In early Hinduism that conduct in men which can be called good consists in conformity to, or almost participation in, the Rta—that great ritual or pattern of nature and supernature which is revealed alike in the cosmic order, the moral virtues, and the ceremonial of the temple. Righteousness, correctness, order, the Rta, is constantly identified with satya or truth, correspondence to reality. As Plato said that the Good was ‘beyond existence’ and Wordsworth that through virtue the stars were strong, so the Indian masters say that the gods themselves are born of the Rta and obey it.

The Chinese also speak of a great thing (the greatest thing) called the Tao. It is the reality beyond all predicates, the abyss that was before the Creator Himself. It is Nature, it is the Way, the Road. It is the Way in which the universe goes on, the Way in which things everlastingly emerge, stilly and tranquilly, into space and time. It is also the Way which every man should tread in imitation of that cosmic and supercosmic progression, conforming all activities to that great exemplar.17 ‘In ritual’, say the Analects, ‘it is harmony with Nature that is prized.’18 The ancient Jews likewise praise the Law as being ‘true’.

This conception in all its forms, Platonic, Aristotelian, Stoic, Christian, and Oriental alike, I shall henceforth refer to for brevity simply as ‘the Tao’. Some of the accounts of it which I have quoted will seem, perhaps, to many of you merely quaint or even magical. But what is common to them all is something we cannot neglect. It is the doctrine of objective value, the belief that certain attitudes are really true, and others really false, to the kind of thing the universe is and the kind of things we are.

The practical result of education in the spirit of The Green Book must be the destruction of the society which accepts it.

However subjective they may be about some traditional values, Gaius and Titius have shown by the very act of writing The Green Book that there must be some other values about which they are not subjective at all. They write in order to produce certain states of mind in the rising generation, if not because they think those states of mind intrinsically just or good, yet certainly because they think them to be the means to some state of society which they regard as desirable.

And this end must have real value in their eyes. To abstain from calling it good and to use, instead, such predicates as ‘necessary’ or ‘progressive’ or ‘efficient’ would be a subterfuge. They could be forced by argument to answer the questions ‘necessary for what?’, ‘progressing towards what?’, ‘effecting what?’; in the last resort they would have to admit that some state of affairs was in their opinion good for its own sake. And this time they could not maintain that ‘good’ simply described their own emotion about it.

February 13th, 2021 by dave dorsey

The Moon Woke Me Up Fifteen Times, Sara Genn, acrylic on canvas

Back when an office copier seemed to be something almost large enough to step into and drive, there was a gag familiar to most people who ever used a big Xerox machine. Someone would inevitably hop up onto it and moon its flashing light to duplicate their naked rear end. It was a trending gag in office spaces for a while: drop trousers, sit on platen glass, press button. Judd Apatow humor. I was amused that all of this was brought to mind by Sara Genn’s marvelous cluster of paintings, assembled into a grid—lovely and suggestive tulip petals, rows of them, each in a color as subtle and lyrical as the tones of Stella’s floral geometry in the Sixties. It’s little wonder her work was awarded finalist status for the Luxembourg Prize last year. Hers was the most beautiful and accomplished of all the work entered for that generous prize.

The Moon Woke Me Up Fifteen Times seduces the viewer gently but relentlessly with the quiet joy of its variations on a single note: a curved bifurcated shape that’s part ravenous Pac Man, part tulip in profile, part suggestion of human life’s anatomical axis in the shape of a Xeroxed moon. What I mean is, along with everything else it evokes, it’s also a colors-of-Benneton cluster of bare derrieres—and that hint of irreverent burlesque puts a cheerful cap on all the work’s other virtues.

Her title is an homage to a Basho poem, “The moon woke me up nine times.” It’s a haiku full of Basho’s characteristic simplicity, profound in its matter-of-fact celebration of the moon’s fleeting beauty and its uncharacteristic sense of humor, a quality more typical of Basho’s poetic descendant, Issa. You can’t tell whether the moon stirred him because it was bright and full, and thus impossible to escape as he slept outside on one of his itinerant quests into the natural world, or did he keep waking up on the hour all through the night because he didn’t want to miss a moment of its luminous silence?

Aside from changing the number of awakenings to suit her formal ambitions, Sara Genn modifies the line into a smiling affirmation of how many times her duplicated moon woke her to rapt attention and celebration of one subtle color after another. But you have to recognize the funny pun packed into the word moon in order to understand this affirmation of her artistic awakening. Alongside that, you realize the line asserts a night of unquenchable desire, the way an old blues lyric is likely to do. But the desire here has been sublimated into a sequence of notes, like a refrain from Erik Satie. The tension between the title’s humor and the simple perfection of those color harmonies, the slight way in which each pair of lips has been parted to create a unique spire of negative white space that disappears into the rich color that surrounds it—the pull between the sincerity of that beauty and the slightly ribald remix of Basho reminds me of how Frederick Hammersley worked so hard to make his viewers smile at his clever titles for small-scale, heartfelt color harmonies. Genn’s work is a close neighbor to Hammersley’s minimalist lyricism. She’s absolutely serious about the radiant beauty she composes in this simple sequence of tones, but she lets her wit give it a title it doesn’t require to do its work. Ever since I first saw this image months ago, I haven’t yet been able to look at it without smiling.

February 10th, 2021 by dave dorsey

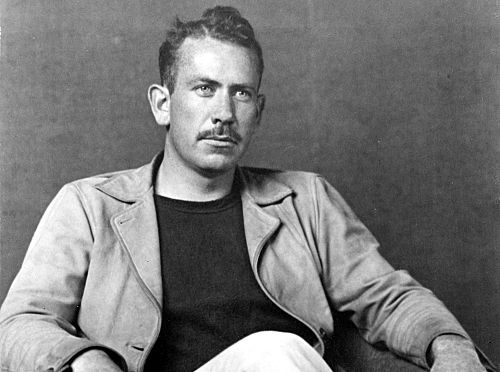

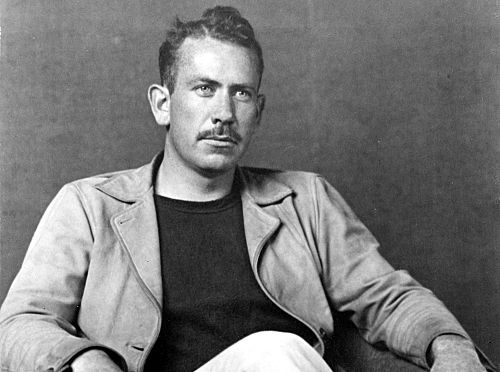

John Steinbeck

From Cannery Row:

Henri the painter was occupied, for Holman’s Department Store had employed not a flag-pole sitter but a flag-pole skater. On a tall mast on top of the store he had a little round platform and there he was on skates going around and around. He had been there three days and three nights. He was out to set a new record for being on skates on a platform. The previous record was 127 hours so he had some time to go. Henri had taken up his post across the street at Red Williams’ gas station. Henri was fascinated. He thought of doing a huge abstraction called Substratum Dream of a Flag-pole Skater.

Henri the painter was not French and his name was not Henri. Also he was not really a painter. Henri had so steeped himself in stories of the Left Bank in Paris that he lived there although he had never been there. Feverishly he followed in periodicals the Dadaist movements and schisms, the strangely feminine jealousies and religiousness, the obscurantisms of the forming and breaking schools. Regularly he revolted against outworn techniques and materials. One season he threw out perspective. Another year he abandoned red, even as the mother of purple. Finally he gave up paint entirely. It is not known whether Henri was a good painter or not for he threw himself so violently into movements that he had very little time left for painting of any kind. About his painting there is some question. You couldn’t judge very much from his productions in different colored chicken feathers and nutshells. But as a boat builder he was superb. Henri was a wonderful craftsman. He had lived in a tent years ago when he started his boat and until galley and cabin were complete enough to move into. But once he was housed and dry he had taken his time on the boat. The boat was sculptured rather than built. It was thirty-five feet long and its lines were in a constant state of flux. For a while it had a clipper bow and a fantail like a destroyer. Another time it had looked vaguely like a caravel. Since Henri had no money, it sometimes took him months to find a plank or a piece of iron or a dozen brass screws. That was the way he wanted it, for Henri never wanted to finish his boat.

Henri had been living in and building his boat for ten years. During that time he had been married twice and had promoted a number of semi-permanent liaisons. And all of these young women had left him for the same reason. The seven-foot cabin was too small for two people. They resented bumping their heads when they stood up and they definitely felt the need for a toilet. Marine toilets obviously would not work in a shore-bound boat and Henri refused to compromise with a spurious landsman’s toilet. He and his friend of the moment had to stroll away among the pines. And one after another his loves left him.

“That painter guy came back to the Palace,” Hazel offered. “Yes?” said Doc. “Yeah! You see, he done all our pictures in chicken feathers and now he says he got to do them all over again with nutshells. He says he changed his—his med—medium.” Doc chuckled. “He still building his boat?” “Sure,” said Hazel. “He’s got it all changed around. New kind of a boat. I guess he’ll take it apart and change it. Doc—is he nuts?” Doc swung his heavy sack of starfish to the ground and stood panting a little. “Nuts?” he asked. “Oh, yes, I guess so. Nuts about the same amount we are, only in a different way.” Such a thing had never occurred to Hazel. He looked upon himself as a crystal pool of clarity and on his life as a troubled glass of misunderstood virtue. Doc’s last statement had outraged him a little. “But that boat—” he cried. “He’s been building that boat for seven years that I know of. The blocks rotted out and he made concrete blocks. Every time he gets it nearly finished he changes it and starts over again. I think he’s nuts. Seven years on a boat.” Doc was sitting on the ground pulling off his rubber boots. “You don’t understand,” he said gently. “Henri loves boats but he’s afraid of the ocean.” “What’s he want a boat for then?” Hazel demanded. “He likes boats,” said Doc. “But suppose he finishes his boat. Once it’s finished people will say, ‘Why don’t you put it in the water? ’ Then if he puts it in the water, he’ll have to go out in it, and he hates the water. So you see, he never finishes the boat—so he doesn’t ever have to launch it.”

January 25th, 2021 by dave dorsey

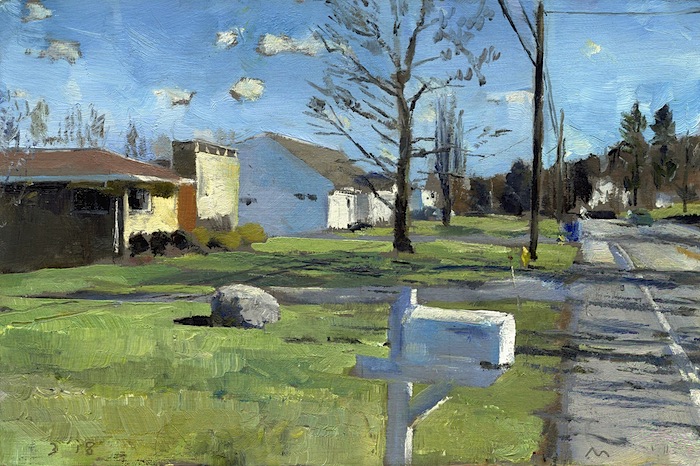

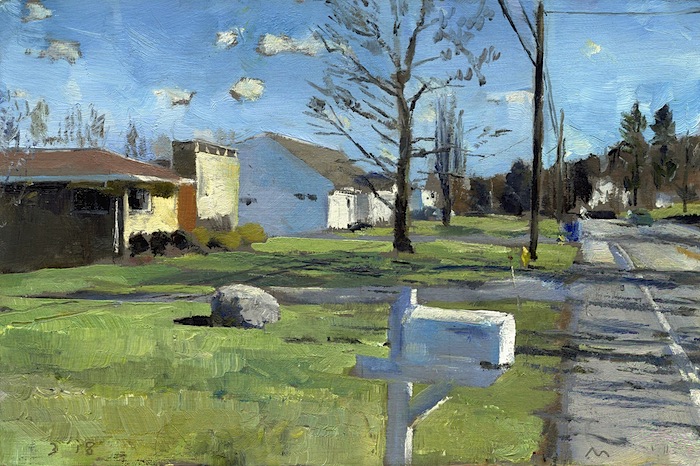

Jim Mott’s painting of a mailbox, after arriving at this spot in his Landscape Lottery.

Jim Mott came by this weekend for a conversation after a long absence, and we picked up more or less where we’d left off last time, talking partly about spirituality, art and God, BLM vs. MLK, his new art project, and some other things I ordinarily don’t talk about, like apple fritters. Though Jim is deeply political, in a way that goes back more to the Sixties than what’s happening now, he’s the least confrontational and least angry political person I know. Many people obsessed with politics seem to have embraced it as a substitute for religion. Jim already has a faith, so politics is simply a way of thinking about how to put that faith into action. What I like about his politics and his religion are the way in which they get submerged into his paint, in a sub-rosa way, neither overt nor strident, producing work that embodies his spirituality rather than illustrates it, if that makes sense. Most of the artists I’m close to are deeply spiritual, but each one in a very different way from the others. Here’s a good portion of our long conversation:

Dave: I went through this spiritual crisis in my teens and it was discovering Van Gogh who got me into it.

Jim: The crisis?

No, he got me into painting. He was so screwed up, but he responded to it by painting. He started by preaching and then went from that to painting, so it was kind of the way he dealt with there being something wrong with the world, or with him.

There’s that romantic notion or tradition that the world doesn’t get it and the individual poet does, so you’re at odds with the world.

It was just the opposite of that with me. I didn’t get it. Life was absurd and I didn’t get it, but that was repugnant to me, so at some level I knew I wasn’t right to have that perception. That was my dilemma. The idea that meaning seemed impossible and this was a crisis, a problem. It seemed the world was pointless and amounted to nothing, and this was horrifying because I couldn’t see out of that mental trap. But there’s a contradiction I didn’t see in this. Camus based The Rebel on a recognition of this contradiction: that people inwardly rebel against nihilism. If nothing matters, then there’s no reason to be dissatisfied with that, just enjoy what you can and that’s that. Why is it horrifying that life seems to amount to nothing? There’s some context in which the absurdity of life is unacceptable but if everything is genuinely pointless how can anything be unacceptable? I couldn’t get to that state of “there’s no way any of any of this can really matter, including my anguish over the impossibility of meaning, so I might as well enjoy life while it lasts.” I couldn’t reconcile myself to this nihilistic certainty I had. So I looked at Van Gogh because I assumed he had to have gone through something like that and responded to it by painting. I’d already been painting pictures of my favorite guitarists, Hendrix, Clapton, Bloomfield. I was in a band, I loved playing my Telecaster. I did the paintings just to have them on my walls. Enlarged copies of album covers. Then I read about Van Gogh and thought, hm, painting is an activity that’s interesting in itself, partly because Van Gogh, this incredibly discontented guy, was so devoted to it. Van Gogh got me to that point. My reading later gave me a way to understand this crisis I’d gone through in a spiritual perspective. So the painting and the spiritual perspective merged.

When you’re doing a good painting you feel like you’re participating in something larger than yourself, at some level it’s about ego-lessness and service. Given all that, the way the art world is all about ego competition and material symbols of success, what would happen if, I don’t know, what happens to you when you buy into that at all. You’re doing what you need to do to advance yourself but, as a result of that, cutting yourself off from your deepest, most authentic sense of what it’s all about – and that awareness of doing something in service to something larger, that awareness and how it imprints itself on the painting, that might be as important to the viewer as all the other qualities that would make a painting conventionally successful.

You mean given the art world’s definition of success. Should you fight it or resist it? That’s always a question.

You’re working to show this . . .

Mystery . .

Right. The art world wants someone who’s world-famous. If someone had handed me world fame, I’m not sure I’d turn it down, but . . .

If it does amount to something, a painting, then if you aren’t known, how do you get it out there? Something essential to your life, how do you connect it to other people?

Even with the significant but moderately narrow level of recognition we get, is it worthwhile to generate a counter-narrative about what it’s all about? As an alternative to the pursuit of the material rewards or even critical recognition. I don’t know. Just to have a small audience to tell that to, you’re still having an impact. Integration is the mission now for me: art and spirit, left and right.

<Behind him on the little end table, I always display his night painting of the Memorial Art Gallery and nearby Tom Insalaco’s painting of an eclair. We have a sidebar discussion of eclairs vs. apple fritters and where to find the best fritters, which was possibly the most impactful part of the entire conversation, but not worth transcribing.)

So what are you painting?

MORE

January 14th, 2021 by dave dorsey

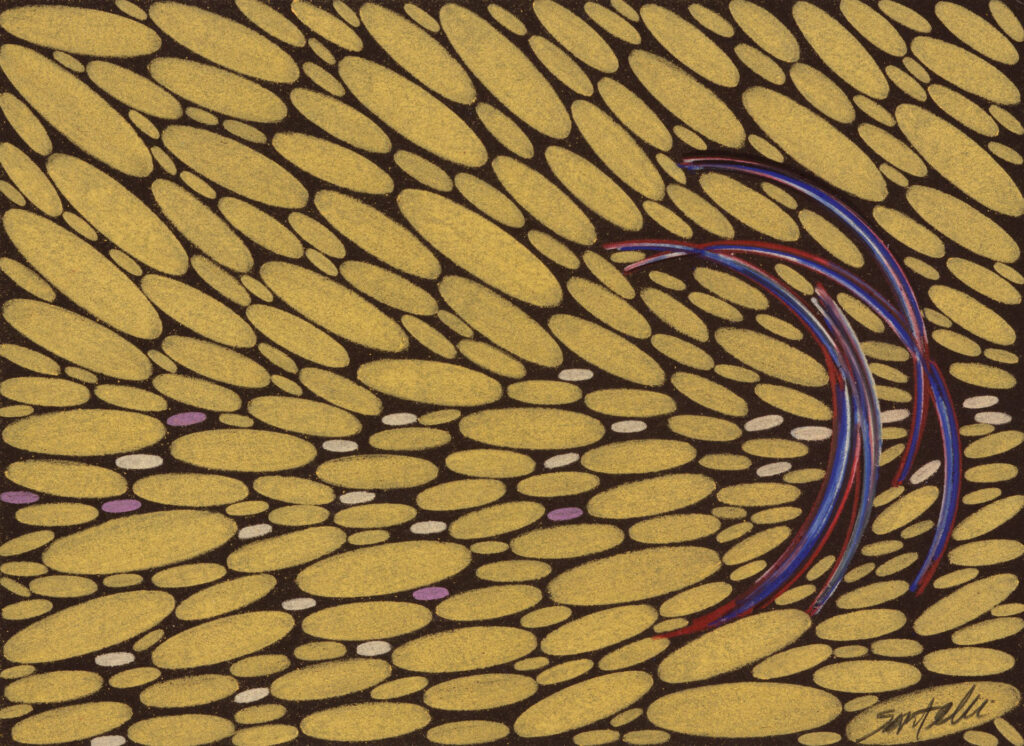

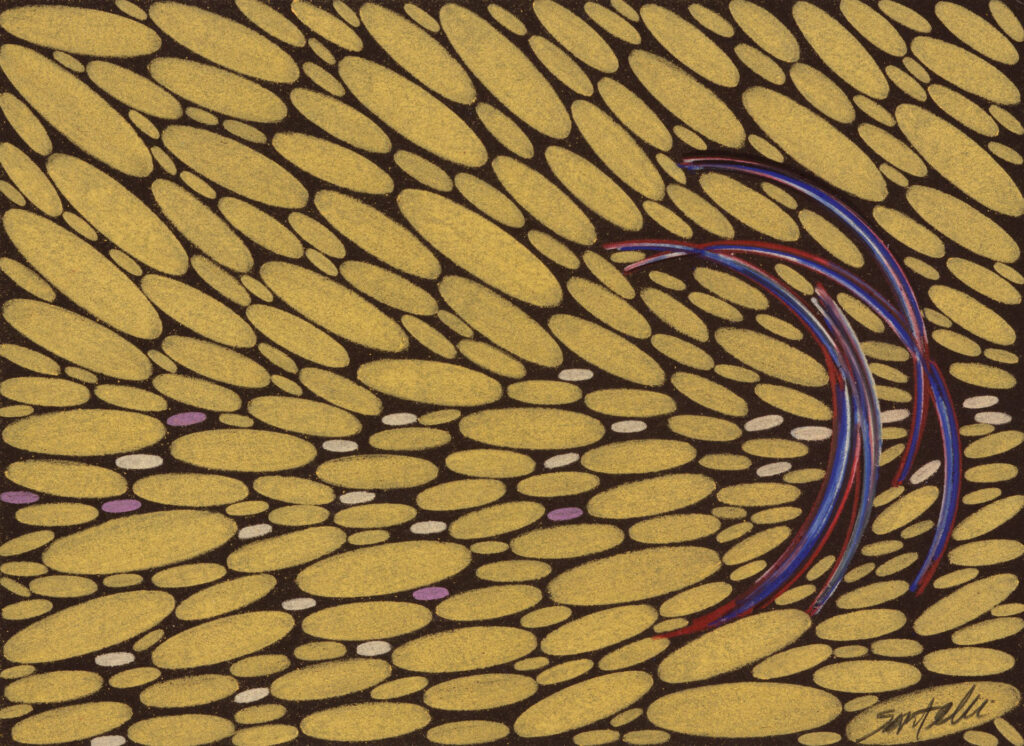

Minstream 17, Bill Santelli, colored pencil on paper

A three-person exhibition, Constellations, featuring paintings, drawings, and installation works by Sara Baker Michalak, Bill Santelli, and Mizin Shin will open shortly at Main Street Arts. It’s curated around the commonality of their work. Each, in different ways, builds a patterned image—loosely or with gridded regularity—that aims for the cosmic. As with every painting, the particulars matter because of their unity within the whole work, but in this case the particulars are mostly effaced within the flow of what’s happening everywhere else.

I’ve known Bill for years and was pleased to hear that he’d been invited into this show, having seen these new drawings on Instagram over the past year. Like his Prismacolor drawings in the Path series, these explorations of thought—the honeycomb of ovals suggestive of thinking’s fragmented flow—represent a patient, repetitive and extremely disciplined practice using the simplest combinations of tone and line. In the Path series, he creates long, languid and pliant streaks of color that evoke tall grass bending in a breeze, where each line creates cells of pale monochrome. They are like leaded panes of stained glass, but also look surprisingly like glimpses of dawn breaking over wetlands.

In these newer drawings, his colors are even simpler and richer, and the minimalism of the Path drawings has been reduced to a grid of loops with less reference to nature. When I asked him to describe what went into the drawings, he wrote “I began these drawings after reading about the concept of ‘mindstream’ in Buddhist philosophy, which is described as . . . the moment-to-moment flow of sense impressions and mental phenomena.” MORE

January 6th, 2021 by dave dorsey

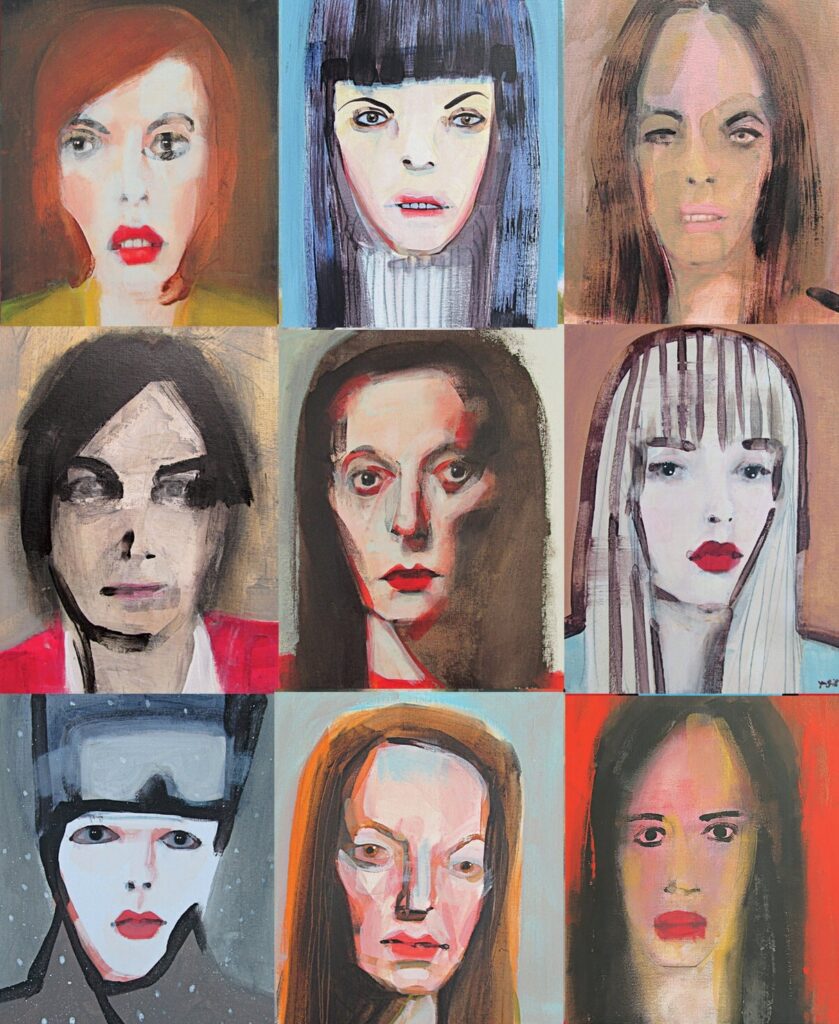

Does anyone still remember those skits on Conan from more than two decades ago where President Clinton would appear as a digital mask worn by Robert Smigel? The writer did a ludicrous, but hilarious, impersonation of Bubba as a Southern party boy living it up and getting away with everything and anything. “I gotsta gotsta have my snacks,” he crowed. And he was talking as much about Monica Lewinski as a side of French fries. A still shot of Clinton’s face on the monitor was lowered into the guest position beside Conan’s desk and within that motionless and grinning face, Smigel’s real-time mouth displaced Clinton’s lips—the writer’s mouth speaking his lines while the President’s face was still frozen into that vote-getting, Teflon grin. It was very funny and outrageous, and it would probably be impossible to perform these days, given much of what was being said, for many reasons. It was so over-the-top and explicit that it took on a reality all its own. (Come to think of it, that would be a good way to describe much of the art world over the last century.)

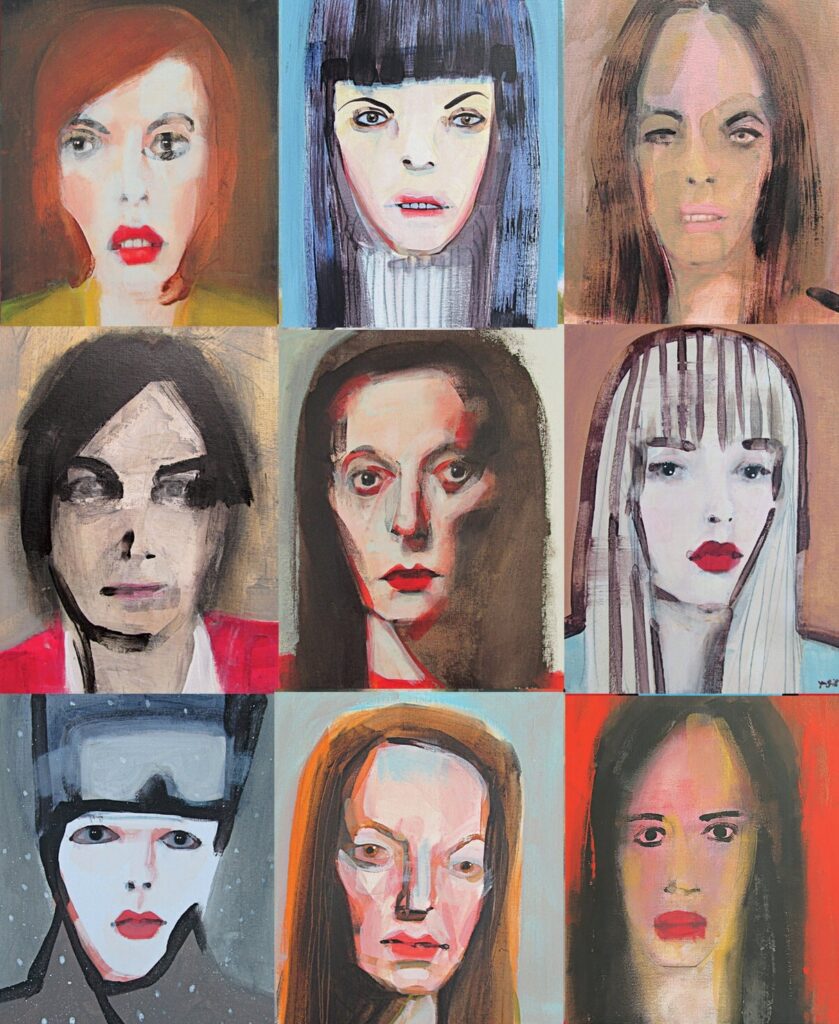

Those Smigel skits were the first thing that struck me when I saw these $100 portraits of women at The New York Times. The eyes in some of them look as if it were somehow possible to have Photoshopped them into the paintings, like Smigel’s good-old-boy accent. Could the paintings have been done on top of the photographs used as a support? Regardless, they’re good. I loved those boundary-testing skits on Conan, because they simply pointed out that when someone is doing what you want him to do, he can get away with nearly everything else in his life. Again, like the rules that once obtained in the art world. (Rewatching the first season of The Wire this week confirmed that lesson as well in terms of Baltimore politics and law enforcement as observed by David Simon.) In my view, the ends are never enough to justify the means, and integrity matters, but I may be in the minority these days.

In these one painting-per-day style portraits, Jean Smith conveys a subject’s eyes with an eerie photographic precision about how the cornea and iris reflect light, but the eyes are framed by a gesturally primitive mask. These souls are looking out at you from behind their own almost graffiti faces. A few of them I wish I’d bought: I mean, why not, for $100? But I like them. Yet her point is to undermine the economy that continues to push the ownership of visual art into an elite economic ghetto of the uber wealthy.

I shouldn’t be talking this way. The work I’m doing now takes weeks without it’s done without interruptions, usually a minimum of four weeks per painting, but also as long as two months with the sort of interruptions that you face when you actually have a life outside the studio, as I still do. No one can afford to put in four to six to eight weeks on a painting that sells for $100. But the point Nick Marino makes in his piece for the Times is that artists aren’t even reaping the actual profits of what has become an extension of the stock market—paintings are now purchased for high prices at the start and then their value is repeatedly inflated through resale or auction, simply as some corollary to day trading Silicon Valley stocks or investing in Bitcoin. (This can’t last. Our financially leveraged economic boom will not continue forever. The art world bubble will burst along with the others, but it may go on for quite a while.)

I love the idea of doing paintings quickly and selling them for unusually low prices. Jim Mott and Harry Stooshinoff are making wonderful, even remarkable paintings in this mode, along with many others. These quick portraits of women offer a continuous experimentation in ways of seeing and representing nothing more than how light lands on an individual face and how the eyes look out from the prison that personhood can seem—when in fact human individuality is the greatest miracle of life.

Excerpts from Marino’s piece:

I can appreciate that beauty has monetary value, particularly for the one and only example of a particular exquisiteness. Someone spent time making it, and that person should be compensated. But even modest artworks can be out of reach for almost anyone who’s not a real estate mogul, shipping magnate, stockbroker or oil baron. Under the sanctimonious cover of “arts patronage,” these plutocrats use art to launder their money, trading up the value of young artists and enriching one another in the process. The artists, meanwhile, get paid only once, on the initial sale. The end result is (artwork) that costs as much as a Honda Civic.

Opting not to use a gallery, Smith listed each of her works on Facebook for the ludicrously low price of $100. She could certainly charge more, but the egalitarian price is the point. It’s her version of the $5 tickets Fugazi used to sell to its all-ages shows — and anyway, she has never needed much to survive. For the past quarter-century, she has lived alone and monastically in an apartment without a sofa or kitchen table (she eats off a filing cabinet), and her monthly expenses, including rent and utilities, total about $1,000. She only needs to sell 10 pieces per month to break even — though that has never been her problem.

Well, that’s all she needs to make if she doesn’t pay taxes. But at that level of income, she wouldn’t need to pay taxes. He points out that having created an insatiable demand for her low-budget art, she can’t keep up with it. The question is, does she keep her prices low or do what the free market naturally does when demand far exceeds supply: let prices rise as far as demand will lift them. I’m guessing it will depend on whether she ever gets a mortgage. I hope she continues to live monastically, as Marino describes her lifestyle. Monastic is almost always unimpeachable as a way to live, especially for an artist. Thoreau, or “Pond Scum” as The New Yorker referred to him once (at the link, you’ll see a note at the bottom of the essay pointing out the original headline), proved that monastic individuality isn’t such a bad way to live until people come in the winter and start cutting up your pond and selling it as blocks of ice.

The other takeaway here: hey, Facebook is still good for something.

November 7th, 2020 by dave dorsey

George Henry, View of Venice, 28 x40, oil on canvas.

As a follow up to my recent post offering two contemporary Tonalist works at Oxford Gallery, this painting of Venice, by George Henry, was on view at the same time as the current work. This one is part of Jim Hall’s available inventory  of historical Tonalist work. It’s an amazing painting, in many ways, not least of which is the impasto, stucco-like, surface of the oil. The paint is applied so generously, in multiple layers, that the tactile quality of its pebbly contours, the way in which shifts in tone create a relief map of color, is extraordinary. The overall impression is of a harbor bathed in a blindingly intense gold at sunset, but the way the paint is organized on the surface of the canvas is what’s most remarkable. Bogert’s life spanned a period of radical changes in technology and culture, and, of course, art.

of historical Tonalist work. It’s an amazing painting, in many ways, not least of which is the impasto, stucco-like, surface of the oil. The paint is applied so generously, in multiple layers, that the tactile quality of its pebbly contours, the way in which shifts in tone create a relief map of color, is extraordinary. The overall impression is of a harbor bathed in a blindingly intense gold at sunset, but the way the paint is organized on the surface of the canvas is what’s most remarkable. Bogert’s life spanned a period of radical changes in technology and culture, and, of course, art.

From Wikipedia: George Henry Bogert (February 6, 1864 – December 13, 1944) was an American landscape painter.In 1911 an exhibit of his work was held at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York, and attracted widespread notice. His work is represented in the permanent collection of the Buffalo Fine Arts Academy.

His work has been displayed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Gallery, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Huntington Library, Pennsylvania Academy, Brooklyn Museum, Edinburgh Museum in Scotland, Shanghai Club in China, Minneapolis Institute of Art, and others, also in private collections, including those of Andrew Carnegie, Clarence Mackay, and Thomas B. Clark.

November 3rd, 2020 by dave dorsey

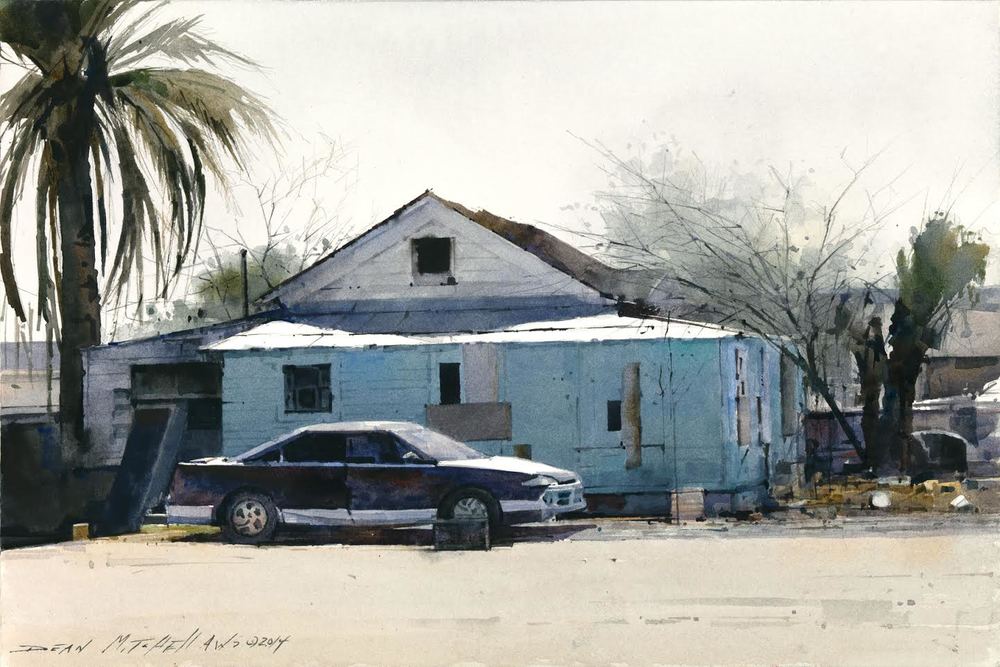

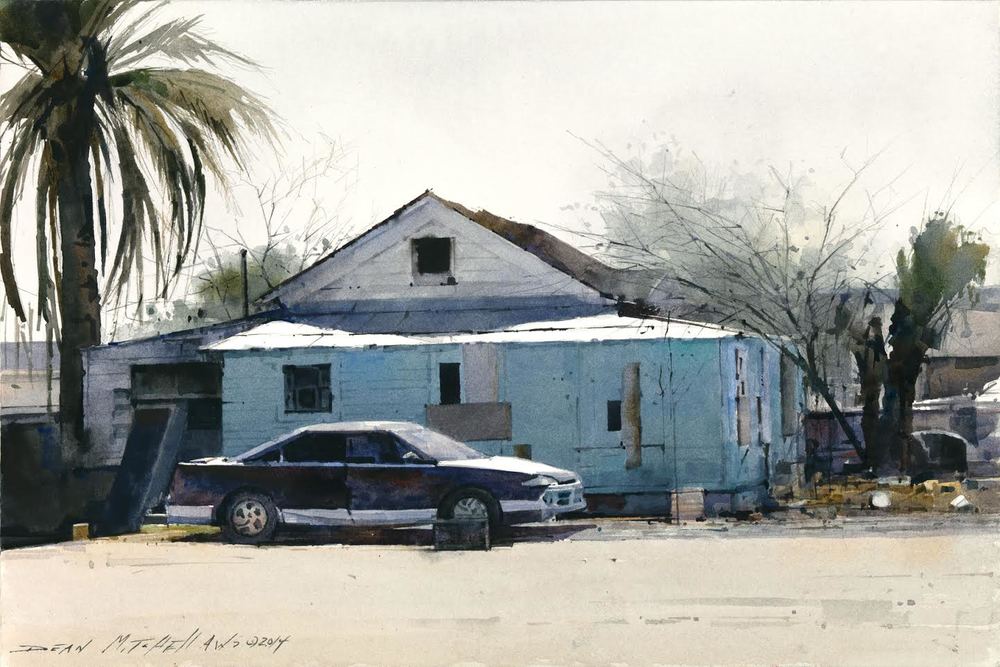

Parking on the Reservation, Dean Mitchell, watercolor.

There are certain painters whose work, the first time I see it, floods me with relief, the way I often feel when I walk through the door of my home after a long road trip. My burdens drop away because I can see, through the work, that everything I need is always at hand, in nothing more than, say, the way sunlight glares off the hood of a car. It’s hard to specify the burdens a painting like this removes, other than what my delight in nothing more than hazy sunlight would suggest: the fundamental human affliction of rarely being able to see things just as they are, being too busy in pursuit of something else not as real. In Dean Mitchell, whose work was recently exhibited at Exeter Gallery, this quality arrives with the mysterious additional blessing of his ability to show things in the world, times of day, the quality of light during certain months and at particular latitudes, as if this abundant, inanimate stage for the petty human craving to be somewhere else, or someone else, is itself perfectly sufficient to be just what it is and nothing else. With Mitchell, there’s no striving to impose himself, interpret, or curate for hackneyed beauties of landscape in favor of a drab bungalow, frail as a lean-to, under a palm tree. Through the title suggests it may be located on a Native American reservation in the West, it is exactly the sort of home one sees in abundance in certain Florida neighborhoods of Sarasota or Tampa or, I would assume, Quincy, where Mitchell grew up in a shack. It’s exactly the sort of place you wouldn’t even notice while taking a residential shortcut off Tamiami Trail on the way to Target or Home Depot. And yet in his painting it’s stunningly beautiful—without his having intentionally beautified the subject in any way. In other words, he has the utter humility and diligence of a photorealist, with scenes that have the instant verisimilitude a good photograph has, though he dispenses with all details that don’t matter through his mastery of watercolor. This is something the medium enables and almost requires. The brevity of the way he indicates clusters of leaves, in other hands, would have the predictable facility of a commercially professional work, but in his paintings it looks original, fresh, and discovered, even though it looks as if he’s hardly trying. And the way he knows what doesn’t matter, what he doesn’t need to show, and elides it into a wash of color with such easy efficiency, makes me envious, self-pitying, and full of awe, as if I were Salieri hiding behind a curtain while Mozart noodles out something immortal with only one hand at the keyboard, maybe eating a sandwich with the other.

October 31st, 2020 by dave dorsey

Doubt, Susie MacMurray, a temporary installation at Southwark Cathedral. London, constructed of butterfly nets.

I went back online recently to get another glimpse of Susie MacMurray’s masterful A Mixture of Frailties, the first work of hers that stunned me when I stumbled upon her solo exhibition at Danese/Corey seven years ago. I was delighted and a little surprised that it continues to resonate in new ways after the passage of years. This time it brought to mind, of all things, The Winged Victory of Samothrace. A frontal view of her headless figure’s prominent shoulders makes them look like sprouting wings or the stumps left behind by their amputation. This hadn’t occurred to me when I saw the actual piece at the exhibition. MacMurray built it around a tailor’s dummy—as she does with her signature garment sculptures—this time enveloping the curvy armature with limp latex gloves. On the floor, they form a train that flows outward and downward in all directions as if the garment were melting. Conversely, the figure seems to rise up out of the floor from under that network of gloves. It’s funny to see in this earthbound dress an ironic echo of the ancient sculpture’s martial grandeur, especially since this work glows with a quietly, almost self-defeating pathos all its own. The fact that you’re looking at what could be a lifetime supply—a life sentence, as it were—of dishwashing gloves both anchors and intensifies, by contrast, the work’s unlikely glory. By creating a ballroom gown out of them, she magically transforms all those flaccid tubes into a spectacular vestment—female power constructed with reminders of male impotence. That’s either a wry sort of Jacobin feminism or honest testimony about how little power any of us actually have. I tend toward the latter. With MacMurray, what looks like an apotheosis always comes with amusing asterisks. The way this dazzling matrix of frailties rises up from the floor, ready for lift-off, seems to echo the triumphant flight promised in the Greek sculpture, but our glove lady isn’t getting airborne any time soon. She is both imprisoned and glorified by all the chores she would love to flee. Feminist interpretations aside, what seems to be embodied here is something wiser and more universal. This beatification of scut work embodies a rare insight into the dignity and worth of long subservience and surrender to a humble task.

All of these impressions reconfirmed for me that much of MacMurray’s work has to do with the unity of polarities in life—in this case, how drudgery and imprisonment and servitude can actually clothe triumph and transformation, or at least can be transmuted to reveal them. A similar truth lies at the heart of the world’s wisdom traditions: the identity of form and emptiness in Buddhism, as well as the notion that your everyday mind is the Buddha, for one. In a different way, the Beatitudes hint at paradoxical realities—the last shall be first—set within a more dramatic spiritual narrative. One can find other corollaries. Her wisdom applies to art-making itself, pointing toward a seminal realization for practicing artists of how the freedom of creative expression dwells within the tedium of repetition, craft and patience. MacMurray’s work requires a great deal of all three. For her, it’s meditative. This equivalence of triumph and drudgery applies to her installations as much as, if not more than, the work of a guru of art-as-process such as Chuck Close. His words are well known: “Inspiration is for amateurs, the rest of us just show up and get to work.” The paradox of the work ethic itself is that what’s good in life can’t be severed from often tedious labor. The process of making one of her pieces embodies this paradox: Medusa required a year to make,

MORE

October 28th, 2020 by dave dorsey

So Close But Not Enough to See, Ryan Schroeder, oil on canvas.

This painting, from a recent group show at Oxford Gallery, has grown on me since I saw it. It fell into a group of paintings interspersed throughout the show that were essentially Tonalist work from various periods. Jim Hall has bought and sold Tonalists for years, and has a stock of examples from well over a century ago from which to pick and  choose an occasional painting for his walls.

choose an occasional painting for his walls.

Another example from the same show is Fran Noonan’s, Quiet Glow. I’ll post a much older example of the tradition shortly, from the same show. Jim’s definition of Tonalism includes artists not often included as part of the school, such as Rothko, but he can make a good argument for the commonalities among them.

September 9th, 2020 by dave dorsey

Matt and Will at Tinker Nature Park a few miles from us.

About a year and a half ago, I set a goal to finish eighteen salt water taffy paintings as the core of a solo show in a year or two. I’m working on the eighth—I sold the first one and have stopped posting pictures of the successive paintings partly as a way to prevent the temptation of selling more. My painting plan has been deferred again and again because of my recurring role as a care provider. Last summer I spent three months mostly taking care of my parents and this summer and fall I will put in about the same period of time helping care for my son, daughter-in-law and grandson. Matthew has migrated here back to Pittsford, NY during the pandemic, after having lived and worked for more than a decade in Los Angeles. He lost his job cutting movie trailers—not lost just yet, but he will be furloughed at least into next year. So he’s unemployed with no assurances about the future and saving money by bringing his family to live with us temporarily in the comparative safety of Western New York, where everything costs less at least for now. What they do when the pandemic recedes depends on his wife’s job as a producer for Ellen Degeneres. Until then, she and Matt will stay with us through her long, arduous recovery from a car accident several weeks ago, during which she will resume working remotely for Ellen via Zoom. Their stay here isn’t all-consuming for us, but has become the center of our activities, putting my work nearly on hold again, as it was last summer and then off and on for months after my father’s death a year ago. I began to regain a regular daily painting schedule over the past week, but have had to put it aside again, I hope briefly, until we settle into a more predictable routine. Our lives have become like a Frank Capra movie where family, friends and neighbors are constantly traversing the interior of our house, bringing food and gifts, standing vigil through some small crisis, and using our grill to prepare a meal.

Again, my painting has been put on hold for the past month until a few days ago when I was able to resume work. By the fall, I should be able to settle back into a productive rhythm on the taffy paintings—one of which has already been exhibited in Ohio at The Butler Institute of American Art and at Manifest Creative Research Gallery. It’s a series of paintings that has required me to develop a diligently repetitive work process—Chuck Close would nod with approval at the monotony of my daily life when I’m at full tilt. My methods are getting more reliable than in the past, my technique is becoming more stringently observant of how areas of tone flow into one another and how the paint sits on the canvas, while I’ve reduced my subject to the simplest and least overtly meaningful objects imaginable. In other words I’ve embarked on a group of paintings that will be my attempt to do what I have been saying for years that painting is uniquely suited to do: convey a glimpse of living wholeness, the entirety of a world, through purely formal means, and doing this with an image devoid of signifiers. Or at least an image in which any signifiers one might deconstruct are entirely beside the point when it comes to the essential work the painting is actually doing. I want paintings entirely devoid of intellectual content. I’m tempted to title at least one painting of taffy in this series: This Is Not Salt-Water Taffy.

I had hoped to complete maybe eighteen of these paintings by next spring and offer them as a solo show and present them as a body of work for consideration at galleries in larger metro areas, eventually. But the world seems to be fast-forwarding through an economic transformation as a result of the corona virus—something that otherwise would have happened over many more years that it may take now. What will be left of the gallery scene after the suspended animation of so much activity in Manhattan and Los Angeles? How have gallery owners survived this devastation? Have they? I got an email maybe two months ago announcing that Danese Corey was ending its exhibition program, without being able to discern whether this means the gallery was ceasing to operate or simply was going to close its brick-and-mortar space on East 22nd St. The announcement shocked me and made me heartsick: I loved or at least respected the work of nearly everyone who exhibited there and considered that shop one of the most intelligent and discerning of any gallery I’d ever visited. It feels like the loss of a good friend. So who else will succumb to the loss of revenue in a sector already beset by the inflation in real estate and the decline of galleries in general as a result of the dominance of art fairs. And aside from that, I doubt I will have quite as many finished paintings as I’d hoped by next spring, now that life keeps recruiting me for other tours of duty. I will likely present whatever I have completed and see what response I get, but I could also postpone all of this another year—yet that would feel like a surrender, backing off from the massive disruptions the world has been undergoing, not only my world’s, but everyone’s. As a result of all this, being on near-hiatus from Instagram and this blog feels oppressive and dispiriting. Yet I want to build this new body of work before I post anything from it, and I’ve been producing little else. I’m also continuing to write, when I can, about art—without yet posting it. A post about my visit to the exhibit of J.D. Salinger relics, as it were, at the New York Public Library, will be forthcoming shortly—it has taken me half a year to catch up and draw together all the notes I took away from it in January.

And, along with my projected solo show, I’m trying to assemble a sequence of essays that could serve as commentary for the show of taffy paintings. Let’s call it, for now, The Salt-Water Taffy Manifesto. If I were to complete writing it by the time I have a full complement of paintings for an exhibit, I will see if I can affordably print and present it as a companion catalog, a little illustrated feuilleton on behalf of purposely insignificant painting. That’s the plan anyway. So I may seem to have disappeared on this blog, but only because life has become more intensely interesting (and demanding) than the act of writing about it. And even so, I intend to pick up a paint brush every day from this morning until next April. That’s a promise to myself. Even if only for the current hour.

July 21st, 2020 by dave dorsey

The Light for the Day, 24″ x 24″, oil on linen

I pause to look at the ordinary places and objects in everyday life and feel the stillness and quietness that historic painters such as Johannes Vermeer, Vilhelm Hammershøi, and Edward Hopper capture with an inexplicable sense of solitude and melancholy.

In my paintings, the mundane surroundings imply transient conditions: such as the disappearance or transformation of old buildings, inexpensive furniture abandoned out on the street, people in the subway heading somewhere, an empty street on holiday, small closing stores in the neighborhood, and dusk at the end of a day.

I am compelled to leave traces of such moments of disappearance on my canvas. The toned-down mood and the elaborate details raise feelings of stillness and quietness which portray an ephemeral presence.

–Yonjae Kim

June 23rd, 2020 by dave dorsey

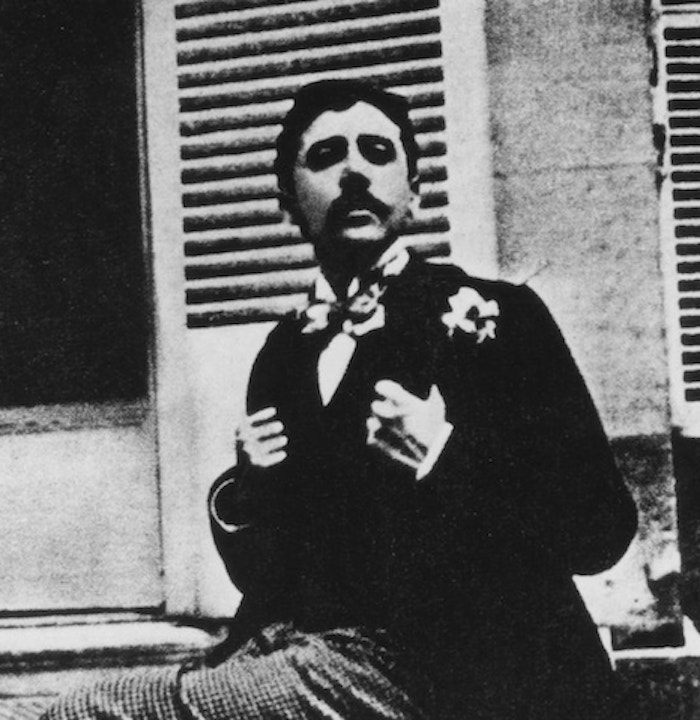

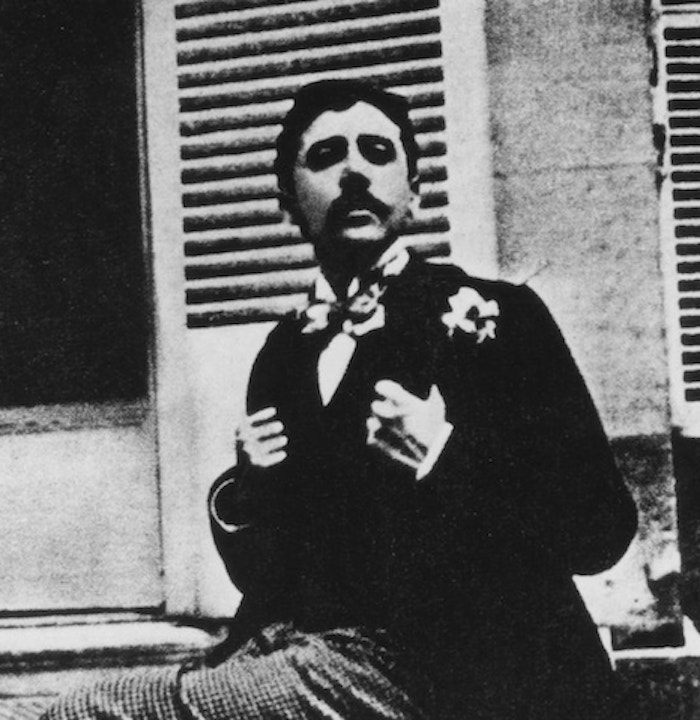

Marcel Proust

From the man who discovered an entire world in a cup of tea:

We have put something of ourselves everywhere, everything is fertile, everything is dangerous, and we can make discoveries no less precious than in Pascal’s Pensees in an advertisement for soap.

–Marcel Proust, The Fugitive

June 5th, 2020 by dave dorsey

Maurice Butler, My God Is Gangsta, 2016, charcoal, spray paint on gessoed paper (detail) — @mauricepbutler.art (Manifest Gallery, Pennsylvania Regional Showcase Exhibition, Dec. 2017-Jan. 2018)

From Manifest, via email to exhibitors and members:

THE STAND

Manifest was built on taking a stand for principles of measured quality, experiential opportunity, philosophical openness, a respect for learned skill and craftsmanship, and a belief that excellence can arise from people of any age, race, gender, background, or geographic origin. Our nonprofit organization was founded sixteen years ago by students and teachers who saw a lack of these things in their world and sought to bring them about, creating a space—a platform if you will—for their manifestation. It was these principles that attracted and gained the involvement of artists from around the world—so many people very different from ourselves.

While this effort was admittedly supported by a privileged relationship to the visual arts and academic art world, even today it gives us a humble microscopic view of the larger position of our fellow Americans and citizens of the world. If you want something good in the world, you have to take action to bring it about. How this is done, the craftsmanship and philosophy, the empathy and truth to inner vision, and the work really matters. The How, What, and Why are everything. We must get these right together. We are seeing this work being done, and it is dangerous, powerful, and inspiring.

Like a work of art this country, this global civilization, must be made such that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Together we are so much more than what we are as individuals. This does not mean we must believe the same beliefs, nor think the same thoughts, or value the same experiences. But we do need to recognize our place as parts of the larger whole, and to embrace it in dynamic respectful balance, celebrating what it means to be here now, recognizing the frailty of a monumental system so much larger and more precious than ourselves.

Across sixteen years Manifest’s exhibits and publications have presented to the public the works of 3,250 artists from all 50 U.S. states and 43 different countries. We do not ask for headshots or ethnicity details when considering submissions of artwork, nor when exhibiting or publishing the final selections. Our belief has been that the artwork speaks for itself. We certainly know that many many of the artists we’ve been blessed with knowing and working with have been very different from ourselves, and this is based on more than just their vast global origins. The fact that so much of the world has been represented by the artists who chose to cross paths here, at Manifest in Cincinnati, Ohio, has meant all the difference in how we have viewed and valued our place in the world. Without them, without so many diverse creative energy sources, Manifest would not be what it is today. It is they who have made Manifest the Neighborhood Gallery for the World.

Now, and always, Manifest condemns the long-standing and systemic racism, inequality and injustice that is experienced by so many in our world. Unity is paramount.

May 9th, 2020 by dave dorsey

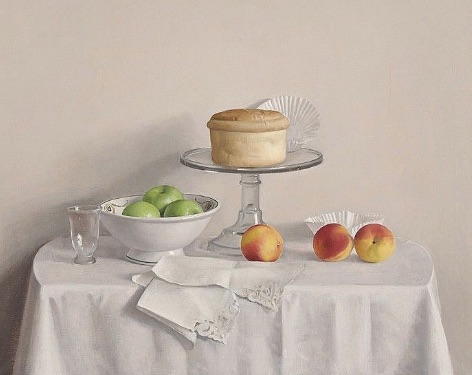

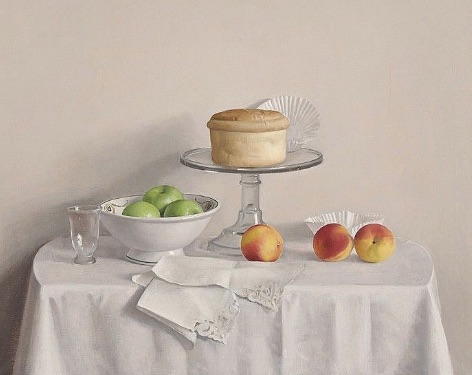

The Pain Surprise, Raymond Han, oil on canvas, 32″ x 36″

Decades ago, my wife and I (with our infant daughter) moved from my first job in Great Falls, Montana to Utica, New York. Within a year or two of that move, I attended two seminal exhibitions at the Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute, where I was enrolled in art instruction for a time. I had consciously refused to attend art school, even though I’d started painting seriously in my mid-teens, and made up for it by working with artists at places like MWP and later at Memorial Art Gallery. I’m going to write elsewhere about the article in Art News that turned me against the world of art in my teens–it’s intellectual pretensions, the post-modern obscurantism of art criticism, the way in which so much art during and after the Sixties arose out of a kind of snotty disdain for the ordinary life of common people. It was all repellent to me, and the artists I loved like brothers at the time–Blake, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Matisse, Braque, Rouault, Klee–struck me as obsolete, historically relevant but offering nothing for a contemporary artist to assimilate. I was too put off by the comparative austerity of Diebenkorn’s abstractions to see how they sprang almost directly from Matisse. But even aside from the way in which the art world seemed like an exclusive club devoted to making itself inaccessible to most people, I believed that I was a late-comer who had no place in the world of contemporary art. I looked at the increasingly sterile ways in which The Next Big Thing in art simply confirmed how all the revolutions were over and there was nowhere new for painting to go, if you understood progress as increasing levels of freedom for visual artists. I didn’t see what was actually going on, the way Arthur Danto did–how Pop Art made anything possible and therefore anything was now acceptable and contemporary. Anything could be art, including the sort of work done in the past. So I continued to paint, out of my own sense of inner necessity—but feeling as if my work had no place in the larger scheme of things, rather than paint and teach, I became a reporter and a writer.

Yet when I found myself walking into “An Appreciation of Realism” at Munson-Williams-Proctor in the 80s, I realized what was still possible, and how I’d missed the way art had become, in a sense, ahistorical. It was an exhibition devoted to representational painting and the roster of artists represented was incredible: Bailey, Estes, Pearlstein, Beal, Kahn, Lennart Anderson, Freilicher, Soyer, Leslie, Resika, Jerome Witkins, Katz, Welliver, Guston, Goings, Cottingham, Close, Bechtle, Fish, Beckman, Paul Georges, Leland Bell, Rackstraw Downes, and Fairfield Porter, along with more than a dozen others. It was an amazingly comprehensive curation of contemporary representational painting by all the names that I continued to study for years after I saw that show. It opened my mind to the possibility that I might actually be able to paint in ways that would belong to what was happening in art around me. It showed me, essentially, that it was possible to be any sort of painter I wanted to be–and all that remained was to spend years figuring out exactly what that was, which I did, slowly and patiently.

What’s interesting to me now is that photo-realism was well-represented but didn’t move me, and that I don’t even recall the work by Fairfield Porter, someone whose paintings I love as much as anyone who has ever picked up a brush. In short order, the arts institute organized a second show which had an even more profound effect on me: a large solo exhibition of Raymond Han’s still lifes. He was born in Hawaii in 1931 and died three years ago in upstate New York. He never got an art degree, but learned from other painters—as I did—and attended the Art Students League. His large still life work in the early 80s was astonishingly masterful: large tables covered in white tablecloths, where he had carefully arranged china, glass, silverware, all of it in tones of white, gray and brown, with small areas of intense color provided by a bit of fruit or flowers. His tables were set back against an off-white wall, his objects casting faint shadows against the wall, all of it like a little domestic city spread out on the fabric, a planned community where each object had been placed with infinite care. He had no desire to paint what he saw in his environment, just as he found it, but created the painting by placing everything where it needed to be to yield a certain kind of balance and serenity—in the way William Bailey does, but with an entirely different feel for his earth tones and matte surfaces from a level, frontal perspective. Han allowed you to look slightly down from in front and above the tabletop. The effect was to give you a glimpse of a snowy landscape, mostly variations of white, with objects and spots of beautiful color all the more powerful for being so rare. Continue reading ‘Han’s solo’

April 12th, 2020 by dave dorsey

Winter, Richard Harrington, acrylic on panel, 48: x 60″

I stumbled across this abstract from my Oregon friend, Rick Harrington, a couple weeks ago, because I was intrigued by something he’d posted on Facebook and wanted to see what he was up to lately. He wrote that he’d completed it a couple years ago, as part of a triptych: all three paintings are posted at his site. He’s been painting what I would call color field barns and color field animals for years. This is presumably a snowstorm, which is already a fairly uniform field of white, but what he’s done here with that foreground white-out is wonderful: the way the intense under-layers of color suggest both natural and internal phenomena, late autumn reds, the yellow glare of the sun in the upper left, and memories of greenery, as if he just went all out with saturated tones in his first strike on the canvas and then started concealing everything he’d done so that you get just little glimpses, hints, of what’s there underneath, which makes the image as much a representation of human psychology as it is a Turner-esque vision of a storm. He paints his barns mostly with rags, and could easily have dispensed with brushes for this one, but I didn’t ask. I was too busy praising him.

April 9th, 2020 by dave dorsey

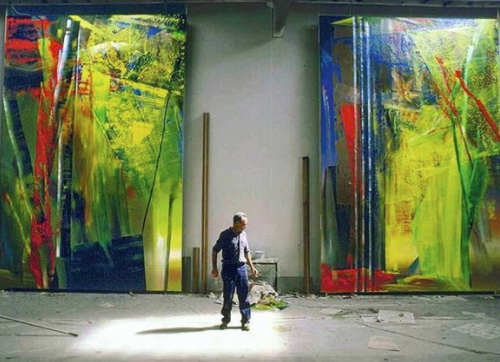

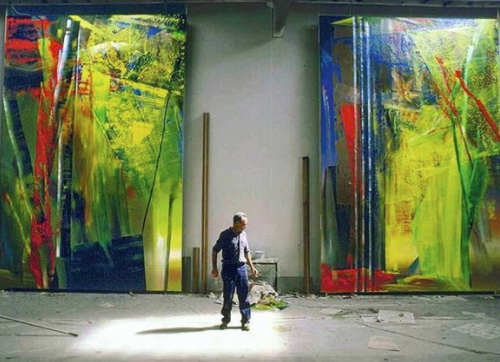

Gerhard Richter with his work

The shot of these two huge abstracts, with Gerhard Richter dwarfed by his work while posing in the shaft of light, appeared on Instagram at abstrac.ted. I can’t find anything quite like them in the compendium of Richter’s work over the decades at Gerhard Richter. I’m wondering if this means he has recently completed these, and if so, it’s an interesting shift in his work. With the exception of a series he did in 2005, all entitled Forest, these two paintings distinguish themselves from almost all of his earlier, extremely flat

Forest

abstracts, obedient to Clement Greenberg’s advocacy of flatness as painting’s most essential, defining characteristic–what, in retrospect, seems like either the silliest or the most obvious proposition about art ever to be embraced in such a hugely influential way. In the bulk of his abstract paintings, Richter experiments with the effects he can get by using large amounts of multiple colors, smearing, masking, scraping, scumbling (on a large scale) one color into another in various ways. In the earlier work, he achieves suggestive effects of luminosity and hints of depth—so that some areas of paint seem to recede to an area just behind the surface. In the Forest series, this is more pronounced: you can discern what might be tree trunks in a foreground, or an underwater scene with tiers of aquatic plant life, against an indeterminate soup behind them, in a way that feels slightly Klee-like. Landscapes blur into twilight. But in this pair of huge canvases, the sense of space is vast, giving a sense of receding vistas. Light seems to shoot down through layers of foliage or enormous skylights, and the vertical shafts to the left in each canvas suggest buildings, or maybe the geometric angles of Richter’s studio itself. In the painting on the left, down in the lower right corner, the rectangular area of softened light seems like a window that offers a glow reaching the viewer from miles away. More than most of his abstraction in the past, this work from Richter, if it’s recent, gives reason to hope he’s trying to find a closer, expressionist truce between abstraction and his celebrated genius as a realist.

April 6th, 2020 by dave dorsey

My new favorite medium.

I’ve been joking with a number of people that having complied with the social isolation required around the world to fight COVID-19, I can’t tell the difference between this and my ordinary life. Such is painting. I still make furtive trips to the supermarket and Home Depot. I paid cash for one small purchase recently and my fingertips did an absurd dance with the clerk’s in our attempt not to touch each other. Meanwhile, running along the Erie Canal’s towpath yesterday, I felt as if dozens of erstwhile isolationists had fled to that nearly empty channel of water, far more people than I would normally see at this time of the year. Walkers, runners, cyclists and in-line skaters were easily able to keep their distance and most were friendlier than they are in the aisles of stores. Maybe I’m just noticing for the first time how eye contact at Wegmans is as rare as on the streets of Manhattan, where people walk under an unspoken edict never to smile at anyone or acknowledge individual faces in the packed flow of pedestrians moving along Fifth Avenue. (Fifth Avenue is as dry, figuratively speaking, as the Los Angeles River these days.)

All of these sequestered hours provide ample time to paint, though I’ve noticed in myself and a number of others—Christopher Burke’s latest post on Instagram talked about his creative rut—that this weird, nearly universal state of suspended animation in society casts a pall on individual effort, for some reason. I’m still painting every day, often for six hours, and making steady progress, but always with an irksome sense that I work more slowly than I would like—yet that doesn’t inspire me to put in longer hours.

So I’m busy enough to be posting new work every few weeks, but I’ve withdrawn to a great degree from Instagram, and have been lax in my posts here, partly because of this languishing sense that everything has come to a halt, but mostly because I’m working on a long series of salt water taffy paintings. I don’t want to post them piecemeal, but rather to wait until the series is nearly done—which will take more than a year. I want to excavate all the possibilities from this radical narrowing of my work. I spoke recently with Rick Harrington about this, telling him that I’m rankling a bit from the constraints of doing what feels in some ways like the same thing over and over again—which is entirely the point of the series, to see how a simple subject accurately rendered can end up working the way an abstract works—and he said, from his long experience with his abstracted barns, that you can learn much by sticking with a particular subject for years and years. After years of struggling to emerge from a fog that resulted from the aftereffects of anesthesia during surgery on his throat, he is back in fourth or fifth gear, reaching a new plateau in his efforts—though the sudden stasis in the economy seemed to threaten his momentum in his galleries. (It hasn’t just yet.) Of this, I’m certain: boxing myself into this narrow line of work will provide ample reward and allow me to learn a lot, and could open some doors. But that doesn’t make it feel any less confining, and doesn’t make it any more pleasant to become a reluctant Punxsutawney Phil and renounce a regular dose of likes on Instagram. It all comes down to hours at the easel; like everything else in life, it’s mostly a matter of showing up and letting the work happen. And maybe pushing for another couple hours beyond the point where you want to get outside and forget the canvas until tomorrow.

One thing I happen to have learned already, in my pursuit of a certain flow of paint in this series, is that from now on, I’m a lifelong convert to Gamblin’s Neo Megilp medium. It is a gel, rather than a fluid, a safer version of Maroger’s, a medium its inventor claimed was the medium of the Old Masters. It’s lead-based, while Neo Megilp uses no lead. Fairfield Porter mixed his own Maroger’s and you can see it in the quality of his marks. I don’t know why I haven’t tried it before now, but it’s marvelous—it gives a consistency to the paint that allows a fluent application, without dripping or visible thinning of the pigment, and stays ductile for a long time, allowing wet-on-wet technique, which is my goal. And a little goes a long way, so that the bottle I’m currently depleting will last for many paintings, even large ones. It’s a joy.

April 3rd, 2020 by dave dorsey

Skye, Chris Baker, gouache, detail.

About 200 hundred pages into the Kilmartin translation of Swann’s Way—I came back to this passage after finding a similar observation in the second book—Proust talks about how his fiction is non-intellectual, and that his lack of ideas originally persuaded him that he couldn’t be a writer. A La Recherche du Temps Perdu shows how his pursuit of love and friendship and social status kept him from discovering his vocation, though ironically the story of his immersion in the illusions of society becomes the actual content of the novel he was unable to write because he was living the events of the book. He had to get lost to find himself.

Here is the passage that says so much, for me, about visual art and the lack of intellectual content or meaning in the paintings I love most (it’s appropriate that visual art was one of the primary inspirations for Proust’s novel and for his style of writing):

Then, quite independently of these literary preoccupations and in no way connected with them, suddenly a roof, a gleam of sunlight on a stone, the smell of a path would make me stop still, to enjoy the pleasure that each of them gave me, and also because they appeared to be concealing, beyond what my eyes could see, something which they invited me to come and take but which despite all my efforts I never managed to discover. Since I felt that this something was to be found in them, I would stand there motionless, looking, breathing, endeavoring to penetrate with my mind beyond the thing seen or smelt . . . It was certainly not impressions of this kind that could restore the hope I had lost of succeeding one day in becoming an author and poet, for each of them was associated with some material object devoid of intellectual value and suggested no abstract truth.

He ignores these intimations for years because they offer him no ideas. He spends years believing he had no talent, no creative virtues, as a result of this lack of intellectual originality. By the end of the novel, the elimination of ideas in favor of the raw phenomena of life, the matrix of felt experience, becomes his sextant, enabling him to bring to life a complex and beautifully superficial world, saturated with a reality to which its inhabitants remain deaf and blind, except in brief, revelatory moments—and those simple moments are what his art is dedicated to triggering, the opening up of a world, intensely familiar but also fresh, surprising, and new. In other words, alive. And through all of it runs the Platonic suggestion that these glimpses are also glimpses of something incorruptible and timeless, hints that the material world is merely the tip of an iceberg invisible to conscious thought.

March 15th, 2020 by dave dorsey

Jasper Beckx’s portrait of Don Miguel de Castro, a Congolese ambassador to the Netherlands, from 1643.Credit…Statens Museum for Kunst

From Black in Rembrandt’s Time, at the Rembrandt Museum in Amsterdam (closed at the moment in the European shutdown.) From the museum’s website: “For years I’ve been looking for portraits of black people like me. Surely there had to be more than the stereotypical images of servants, enslaved people or caricatures? I found the alternative in Rembrandt’s time: a gallery of portraits of black people who are depicted with respect and dignity.” – Stephanie Archangel, Guest Curator

of historical Tonalist work. It’s an amazing painting, in many ways, not least of which is the impasto, stucco-like, surface of the oil. The paint is applied so generously, in multiple layers, that the tactile quality of its pebbly contours, the way in which shifts in tone create a relief map of color, is extraordinary. The overall impression is of a harbor bathed in a blindingly intense gold at sunset, but the way the paint is organized on the surface of the canvas is what’s most remarkable. Bogert’s life spanned a period of radical changes in technology and culture, and, of course, art.

of historical Tonalist work. It’s an amazing painting, in many ways, not least of which is the impasto, stucco-like, surface of the oil. The paint is applied so generously, in multiple layers, that the tactile quality of its pebbly contours, the way in which shifts in tone create a relief map of color, is extraordinary. The overall impression is of a harbor bathed in a blindingly intense gold at sunset, but the way the paint is organized on the surface of the canvas is what’s most remarkable. Bogert’s life spanned a period of radical changes in technology and culture, and, of course, art.

choose an occasional painting for his walls.

choose an occasional painting for his walls.